© Hong Kong Academy of Medicine. CC BY-NC-ND 4.0

REMINISCENCE: ARTEFACTS FROM THE HONG KONG MUSEUM OF MEDICAL SCIENCES

John Christopher Thomson: the overlooked

physician

TW Wong, FHKAM (Emergency Medicine); Moira Chan-Yeung, FRCP, FRCPC

Members, Education and Research Committee, Hong Kong Museum of Medical Sciences Society

Dr John Christopher Thomson (Fig) was a physician

whose enormous contributions to the development

of medicine in Hong Kong should be recognised

and highlighted. Born in 1863 in Lockerbie,

Scotland, Thomson graduated from The University

of Edinburgh with a Bachelor of Medicine and

Master of Surgery in 1888 and earned a Doctor of

Medicine in 1892. He became a missionary and

was sent by the London Missionary Society as the

first Medical Superintendent of Alice Memorial

Hospital (AMH), a charity hospital founded in 1887. As Medical Superintendent of AMH, Thomson

was on the teaching staff of the Hong Kong College

of Medicine (HKCM), which was established by

prominent local medical practitioners such as Dr

Patrick Manson, Dr James Cantlie, and others.1

Thomson taught pathology, materia medica, and

therapeutics over the years. In 1891, he became the

College’s secretary; later, he also took over the role

of Director of Studies, holding both positions until

his retirement in 1909.2 It was due to Thomson’s

energy, indomitable perseverance, and willingness to serve that the HKCM continued to operate until

it merged with The University of Hong Kong to

become the Faculty of Medicine.3 He was highly supportive of HKCM graduates and believed that

they were well trained and qualified for work in

Hong Kong.4

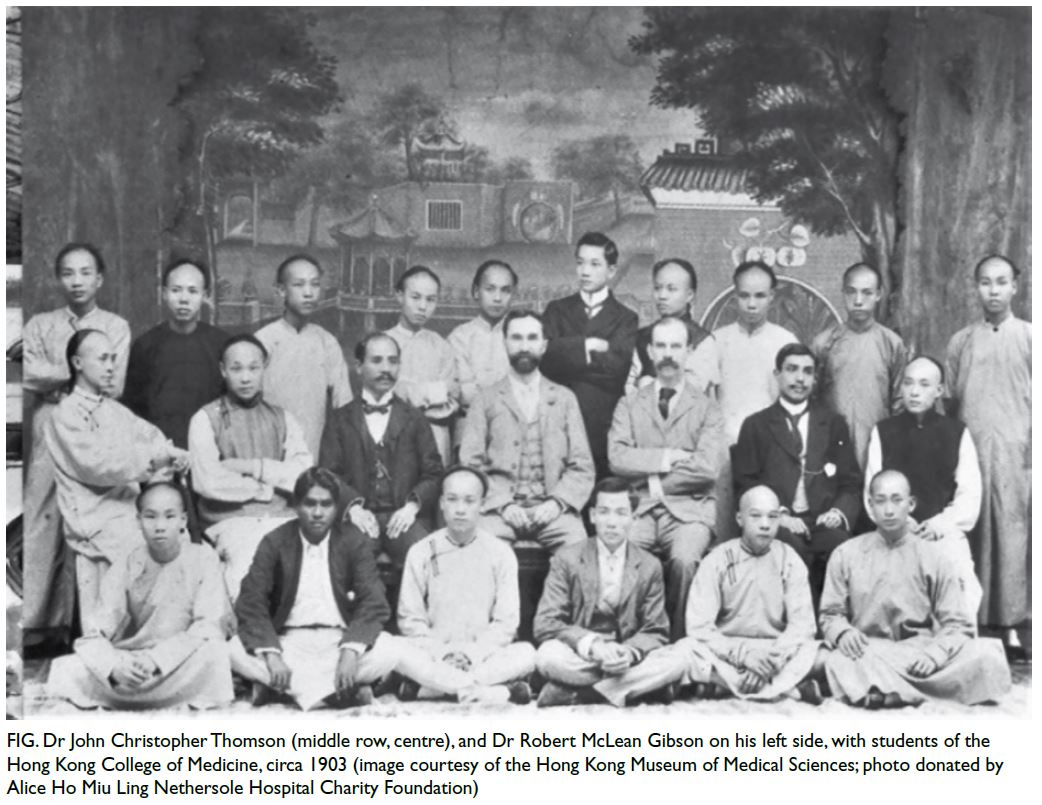

Figure. Dr John Christopher Thomson (middle row, centre), and Dr Robert McLean Gibson on his left side, with students of the Hong Kong College of Medicine, circa 1903 (image courtesy of the Hong Kong Museum of Medical Sciences; photo donated by Alice Ho Miu Ling Nethersole Hospital Charity Foundation)

In 1897, Thomson resigned from AMH and,

after a brief stint in private practice, he joined the

Government Medical Department. His duties varied

over the years, but his main role was as Inspecting

Medical Officer of Tung Wah Hospital (TWH),

where he contributed enormously. In 1896, following

the 1894 bubonic plague epidemic, a commission

was appointed to examine the workings of TWH,

which was a Chinese hospital inaugurated in 1872

that practised traditional Chinese medicine (TCM).

At the onset of the 1894 epidemic, the hospital

was found to have 20 undiagnosed cases and it

became the epicentre of plague in Hong Kong. The

commissioners therefore recommended that the

hospital discontinue its political activities and focus

on its medical work such as improving sanitation

and introducing Western medicine. To ensure these

changes took place, the government appointed

Thomson to supervise the sanitary reforms and Dr

King-ue Chung, the hospital’s new resident surgeon,

to advance the introduction of Western medicine.

Patients admitted to the hospital were to be given

the choice of either TCM or Western medicine.5 The

introduction of Western medicine to TWH was an

important milestone in its development.

Thomson was able to effectively implement the

sanitary reform and supervised the introduction of

Western medicine without arousing the antagonism

of local Chinese elites. His strategies were as follows:

- Rearrangement of the wards. A receiving ward was established for all new cases to be admitted. Patients were examined by Chung who then reviewed them with Thomson. Cases of bubonic plague and smallpox were sent to the Kennedy Town Infectious Diseases Hospital as soon as possible. Patients with other diagnoses, such as malarial fevers, diarrhoea and dysentery, beriberi, and general medical cases, were accommodated in different wards to lessen the degree of cross-infection and allow easier management. Two new wards were built on the compound for surgical patients.

- Increasing ventilation in the hospital. To prevent overcrowding, the maximum number of patients allowed in each ward was determined by the size of the ward.

- Sanitary measures including the removal of commodes from the wards as soon as possible, changing patients’ clothing twice a week and all bedding once a week, and disposal of soiled and old clothing and quilts were implemented. Jeyes Fluid, a disinfectant, was used to clean the wards and the bathrooms frequently. Thomson carried out inspections of the hospital twice a week to ensure that the hospital was clean and sanitary. Clean quarters were provided for Chung and the hospital staff.5

- The hospital was required to keep good records detailing the numbers of daily admissions, discharges, and deaths, as well as the number of bodies brought in for which there was a diagnosed cause of death.5 Thomson discussed with Chung the causes of death for patients who died on the wards and those brought in to the mortuary. When foul play was suspected or an obscure case of public health importance was found, orders from the coroner for a post-mortem examination would be sought.6 The cause of death of each patient in TWH was determined and recorded.

As a result of these measures, the mortality

of inpatients of TWH, which had been around 50%,

decreased to about 35% to 40% for those who received

treatment with TCM. For those who received

treatment using Western medicine, the mortality

was 15% to 20%.7 Over the years, Thomson brought in students from the HKCM, such as King-fai Tang,

Chik-fan Leung,8 and Ko-tsun Ho9 to help Chung

as the inpatients of TWH increasingly opted for

treatment with Western medicine. The introduction

of Western medicine proceeded smoothly and, in

1908, the director of TWH even permitted teaching

Western clinical medicine in the hospital—this was

a major shift in the attitude of the Hospital Board

and a success that could largely be attributed to

Thomson’s efforts.

Thomson’s other major contribution was in

malaria control. The incidence of malaria in the

civilian population then was around 400 per 100 000,

with a 50% death rate.10 11 During a period of leave

in England, Thomson learned about malaria and

mosquitoes. On his return in 1900, he carried out

a systematic study on mosquitoes. He was the first

to identify three species of Anopheles mosquitoes

which carry the malarial parasite, Anopheles sinensis,

Anopheles maculates, and Anopheles fatigans, in

Hong Kong.12 His work gave support to the new malaria-mosquito theory and received acclaim in

London.13

Thomson retired from government service in

1909 because of debilitating sprue and left Hong

Kong.14 His service, which he carried out with courtesy and consideration, was quite different

from that of some British colonists of the time, and as such was highly appreciated by the Chinese community. He was a physician who, by supporting the HKCM and introducing Western medicine to TWH, contributed greatly to the development of medicine in Hong Kong and his work has not, thus far, been appreciated appropriately.

References

1. Ho FC. People and institutions. In: Western Medicine for Chinese: How the Hong Kong College of Medicine

Archived a Breakthrough. Hong Kong: Hong Kong University Press; 2017: 34-6. Crossref

2. Cunich P. The Hong Kong College of Medicine, 1887–1915. In: A History of The University of Hong Kong: Volume

1, 1911–1945. Hong Kong: Hong Kong University Press; 2012: 40-73.

3. Presentation to Dr JC Thomson. South China Morning Post. December 11, 1909.

4. Ching F. The bubonic plague and a degree of recognition. In: 130 Years of Medicine in Hong Kong: From the College of Medicine for Chinese to Li Ka Shing Faculty of Medicine. Singapore: Springer; 2018: 47-76. Crossref

5. The Hon TH Whitehead. Commissioners’ Recommendations. Tung Wa Hospital Report. Hong Kong Sessional

Papers, 1896. The Government of Hong Kong, xxx-xxxii.

6. Annual Reports of the Inspecting Medical Officers of Tung Wa Hospital for the years 1897 to 1903. Hong Kong

Sessional Papers, 1898 to 1904. The Government of Hong Kong.

7. Chan-Yeung M. The Chinese hospital (Tung Wah): its rise, decline, and rebirth. In: A Medical History of Hong Kong: 1842–1941. Hong Kong: The Chinese University of Hong Kong Press; 2018: 55-80. Crossref

8. Report of the Inspecting Medical Officer of the Tung Wa Hospital. Hong Kong Administrative Report, 1908. The Government of Hong Kong. Available from: https://digitalrepository.lib.hku.hk/catalog/p554f3238#?xywh=189%2C664%2C1421%2C1661&c=&m=&s=&cv=. Accessed 6 Jun 2023.

9. Ho FC. Some unusual and some outstanding personalities. In: Western Medicine for Chinese: How the Hong Kong College of Medicine Achieved a Breakthrough. Hong Kong: Hong Kong University Press; 2017: 142-70. Crossref

10. Ayres PB. The Colonial Surgeon’s report, for 1885. Hong Kong Sessional Papers, 1886. The Government of Hong

Kong. Available from: https://digitalrepository.lib.hku.hk/catalog/7p88k368r#?c=&m=&s=&cv=&xywh=-336%2C-296%2C2760%2C1566. Accessed 6 Jun 2023.

11. Ayres PB. The Colonial Surgeon’s report for 1890. Hong Kong Sessional Papers, 1891. The Government of

Hong Kong. Available from: https://digitalrepository.lib.hku.hk/catalog/kw52qx45q#?xywh=-1866%2C-157%2C5530%2C3138&c=&m=&s=&cv= Accessed 6 Jun 2023.

12. Thomson JC. Report regarding the mosquitoes that occur in the colony of Hong Kong. Enclosed in Gascoigne to

Chamberlain, 18 August 1902, CO 129/312/365, 224-6.

13. JM Green to CP Lucas 26 September 1902, CO 129/312/365, 219.

14. The Governor to the Earl of Crewe, Secretary of State for the Colonies, 13 September 1909, CO 129/357/265, 509-10.