© Hong Kong Academy of Medicine. CC BY-NC-ND 4.0

ORIGINAL ARTICLE (HEALTHCARE IN MAINLAND CHINA)

Asthenopia prevalence and vision impairment severity among students attending online classes in low-income areas of western China during the COVID-19 pandemic

Y Ding, PhD1; H Guan, PhD1; K Du, PhD2; Y Zhang, PhD1; Z Wang, MD1; Y Shi, PhD1

1 Center for Experimental Economics for Education, Shaanxi Normal University, Xi’an, China

2 College of Economics, Xi’an University of Finance and Economics, Xi’an, China

Corresponding author: Dr H Guan (hongyuguan0621@gmail.com)

Abstract

Introduction: This study explored the impact of

online learning during the coronavirus disease 2019

(COVID-19) pandemic on asthenopia and vision

impairment in students, with the aim of establishing

a theoretical basis for preventive approaches to

vision health.

Methods: This balanced panel study enrolled

students from western rural China. Participant

information was collected before and during

the COVID-19 pandemic via questionnaires

administered at local vision care centres, along

with clinical assessments of visual acuity. Paired t

tests and fixed-effects models were used to analyse

pandemic-related differences in visual status.

Results: In total, 128 students were included (mean

age before pandemic, 11.82 ± 1.46 years). The mean

total screen time was 3.22 ± 2.90 hours per day

during the pandemic, whereas it was 1.97 ± 1.90

hours per day in the pre-pandemic period (P<0.001).

Asthenopia prevalence was 55% (71/128) during the

pandemic, and the mean visual acuity was 0.81 ± 0.30

logarithm of the minimum angle of resolution; these

findings indicated increasing vision impairment,

compared with the pre-pandemic period (both

P<0.001). Notably, asthenopia prevalence increased

by two- to three-fold, compared with the pre-pandemic period. An increase in screen time while learning was associated with an increase in

asthenopia prevalence (P=0.034).

Conclusion: During the COVID-19 pandemic,

students spent more time on online classes, leading to

worse visual acuity and vision health. Students in this

study reported a significant increase in screen time,

which was associated with increasing asthenopia

prevalence and worse vision impairment. Further

research is needed regarding the link between online

classes and vision problems.

New knowledge added by this study

- Online learning has become increasingly popular during the coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic. Students reported a nearly twofold increase in screen time during the pandemic, compared with the pre-pandemic period.

- Students reported greater asthenopia prevalence and demonstrated worse vision impairment during the pandemic, compared with the pre-pandemic period.

- Screen time was associated with asthenopia prevalence but not with the progression of vision impairment.

- Policymakers should carefully consider the prevalence of asthenopia and progression of vision impairment among students who are increasingly using digital devices and enrolling in online classes.

- Policies regarding vision care should be implemented in response to the increasing use of online learning approaches.

Introduction

The World Health Organization announced that the

coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) outbreak had

become an international public health emergency on 30 January 2020; on 11 March 2020, it declared that

the outbreak had become a pandemic.1 Governments

and public health authorities worldwide implemented

public health policies to reduce the risk of viral transmission, including strict physical distancing,

severe travel restrictions, and the closure of many

businesses and schools. On 25 January 2020, China’s

Central Government announced a nationwide travel

ban and quarantine policy2; it initiated nationwide

school closures as an emergency measure to prevent

the spread of COVID-19.3 Thus, >220 million school-aged

children and adolescents were confined to their

homes; online classes were offered and delivered via

the internet.4

Vision problems are public health challenges;

among school-aged children, these problems

often involve asthenopia and vision impairment.

Asthenopia is defined as a subjective sensation of

visual fatigue, eye weakness, or eyestrain; it can

manifest through various symptoms, including

epiphora, ocular pruritis, diplopia, eye pain, and

dry eye.5 Vision impairment is defined as visual

acuity (VA) of 6/12 or worse in either eye6; it is

often caused by uncorrected refractive errors, and

its estimated prevalence is 43%.7 Although both

asthenopia and vision impairment have negative

effects on students, the effects of vision impairment

are greater. A previous global analysis revealed

that vision impairment was present in 12.8 million

children aged 5 to 15 years, half of whom lived in

China.8 Moreover, students with vision impairment have lower scores on various motor and cognitive

tests.9 10

Excessive use of digital devices contributes

to increases in asthenopia prevalence and vision

impairment among school-aged children.4 11 12 13 14 15 The

COVID-19 pandemic has led to increased use of

digital device–supported online classes,16 17 18 which

require extended exposure to those devices.19 20

Importantly, long durations of exposure to digital

devices can contribute to many vision problems in

children.14

Asthenopia and vision impairment related

to the excessive use of digital devices during the

COVID-19 pandemic have been investigated in

developed countries and urban China.4 11 12 To our

knowledge, no similar studies have been conducted

in western rural China. Additionally, online classes

are increasingly implemented in rural areas, and the

use of digital devices is becoming more prevalent11;

thus, there is a need for research that focus on vision

health in students.

The primary purpose of this study was to

assess screen time, asthenopia prevalence, and vision

impairment progression during the COVID-19

pandemic among students in western rural China.

To achieve this goal, we first conducted a general

descriptive analysis of student characteristics and

screen time trends before and during the pandemic.

We then investigated the prevalence of asthenopia

and progression of vision impairment. Finally,

we explored factors influencing the prevalence of asthenopia and progression of vision impairment before and during the pandemic.

Methods

Setting

This study focused on areas that were broadly

representative of rural western China because of

limited resources. Thus, the study was conducted

in Shaanxi and Ningxia regions in western China.

In 2019, the per capita gross domestic product in

Shaanxi Province was US$10 167; this is similar to

that in Ningxia Autonomous Region (US$8236).21

Sample selection

Vision data were acquired from local vision care

centres (VCs), which had been established by the

Center for Experimental Economics in Education

at Shaanxi Normal University, in cooperation

with county-level organisations such as the local

education ministries and hospitals.

Before the pandemic, VC screenings were

performed in each county, except during summer

and winter vacations. Staff conducted one to two

screenings per week (covering 2 to 4 schools); they

completed one round of screening in one town each

month. In practice, approximately 1 year is needed

to complete one round of vision screening for all

eligible children in a particular county. The second

round and subsequent rounds of vision screening

were performed using a similar workflow. After the completion of vision screening, students who

required further assessment were referred to the VC

for full eye and refractive examinations. This study

included students who had visited the VC 3 months

before the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic.

During the pandemic, VC staff could not

attend schools to perform vision screenings. To

maintain vision screening services for students,

we telephoned all students who had visited the VC

before the pandemic. Participants in this panel study

were students who participated in data collection

before and during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Data collection

We conducted two cycles of surveys in the VC. The

first survey cycle was conducted from October to

December 2019 (before the pandemic); the second

survey cycle was conducted among a group of

students who visited the VC for follow-up from July

to December 2020 (during the pandemic), based on

their enrolment in the study before the pandemic.

The same information was collected during the

two survey cycles. During the vision screening

process, VC staff administered questionnaires to

students for collection of the following information:

sex (male=1), age, ethnicity (Han=1), residence

(non-rural=1), only-child status (yes=1), parental

education (parents with ≥12 years of education=1),

and parental migration status (one or both out-migrated=1; defined as one or both parents worked

away from home during the semester). Household

assets were calculated by summing the values of 13

items owned by the family, in accordance with the

China Rural Household Survey Yearbook.22

The survey also included the collection of

information regarding screen time and asthenopia.

Students completed a previously described, self-administered

questionnaire concerning mean time

spent throughout the day on near activities (including

computer and smartphone use, television viewing,

and studying/homework after school). Reports of

time spent on near activities during different parts

of the day were categorised as screen time while

learning and screen time while playing. Information

regarding asthenopia was collected via three

questions focused on ocular discomfort: whether the

student had experienced dry eyes (yes=1), eye pain

and swelling (yes=1), and eye fatigue and watery eyes

(yes=1). Asthenopia was defined as the presence

of at least one of these three types of vision health

problems (yes=1).23 Furthermore, information

regarding VA was collected when students visited

the VC. The optometrist in the VC conducted a VA

test to measure the clarity of each student’s vision.

All students completed VA tests without refractive

correction; students with spectacles completed VA

tests with their routine method of vision correction.

The questionnaire regarding asthenopia was developed and reviewed by a group of health experts

from Shaanxi Normal University and Zhongshan

Ophthalmic Center, a well-known ophthalmology

institution in China. The included questions were

constructed to ensure that they could be clearly

understood by students aged 9 to 17 years with the

aid of trained VC staff. These three questions can

serve as good indicators of symptoms representing

different degrees of asthenopia in students, and they

have been used in previous research.23

Visual acuity assessment

Visual acuity was assessed using Early Treatment

Diabetic Retinopathy Study tumbling-E charts

(Precision Vision, La Salle [IL], United States). In an

indoor area with sufficient light, VA was separately

assessed for each eye without refraction at a distance

of 4 m. Students were first examined using a 6/60

line; if they correctly identified the orientation of

at least four of five optotypes, they were examined

using a 6/30 line, followed by a 6/15 line and a 6/3

line. In this manner, the VA for an eye was defined as

the lowest line on which four of five optotypes were

correctly identified. If the participant could not read

the top line at a distance of 4 m, they were tested at a

distance of 1 m, and the VA result was divided by 4.

In this study, VA levels were calculated and

compared using the logarithm of the minimum angle

of resolution (logMAR) scale, which is a linear scale

with regular increments that offers a reasonably

intuitive interpretation of VA measurement.24 In this

study, vision impairment was defined as logMAR

≥0.3 (ie, VA of 6/12 or worse) in either eye.

Statistical methods

This balanced panel study compared student

data between two periods (before and during

the COVID-19 pandemic). Mean screen time,

asthenopia prevalence, and vision impairment

progression were compared among students using

t tests, after stratification according to various

demographic and behavioural factors. Fixed-effects

logistic and regression models were used to explore

factors influencing the prevalence of asthenopia and

progression of vision impairment before and during

the pandemic. Fixed-effects models were adjusted

for sex, age, ethnicity, rural or non-rural residence,

only-child status, parental migration status, parental

education level, household assets, screen time while

learning, and screen time while playing. All analyses

were performed using Stata Statistical Software,

version 14.1 (StataCorp, College Station [TX],

United States). All tests were two-sided, and P values

<0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Results

This study included 128 students from western rural China (mean age before pandemic, 11.82 ± 1.46

years; mean age during pandemic, 12.32 ± 1.54 years;

80 girls [62.5%] and 48 boys [37.5%]). All participants

had vision impairment and were attending online

classes (Table 1).

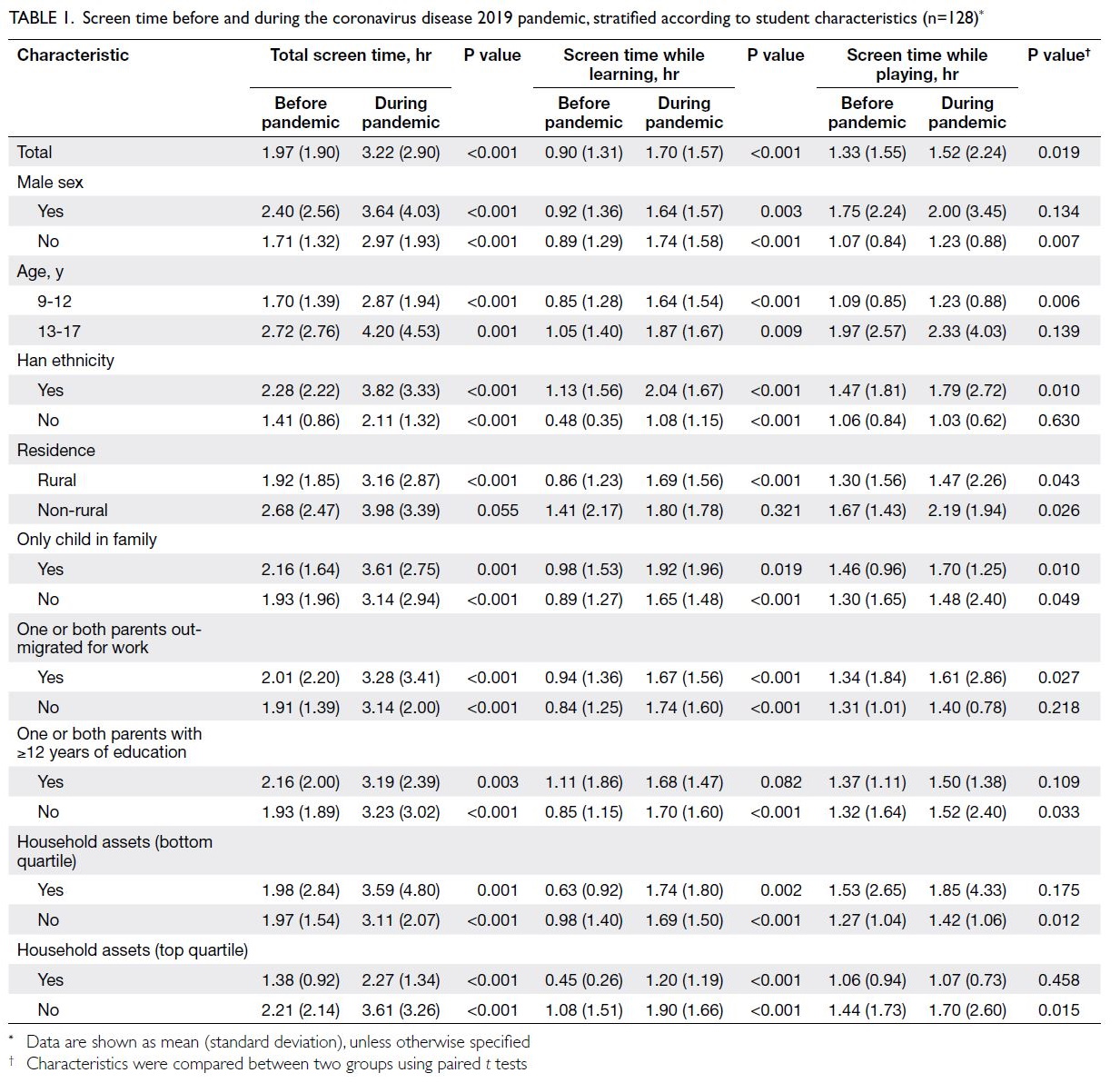

Table 1. Screen time before and during the coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic, stratified according to student characteristics (n=128)

During the pandemic, screen time significantly

increased because of enrolment in online classes.

The mean total screen time during the pandemic was

3.22 hours per day, compared with 1.97 hours during

the pre-pandemic period (P<0.001). The mean

screen time while learning during the pandemic was

1.70 hours per day, compared with 0.90 hours during

the pre-pandemic period (P<0.001); the mean screen time while playing during the pandemic was 1.52

hours per day, compared with 1.33 hours during the

pre-pandemic period (P=0.019). Additionally, rural

students had significantly greater screen time while

learning during the pandemic, compared with the

pre-pandemic period (P<0.001); there was no such

difference among non-rural students (Table 1).

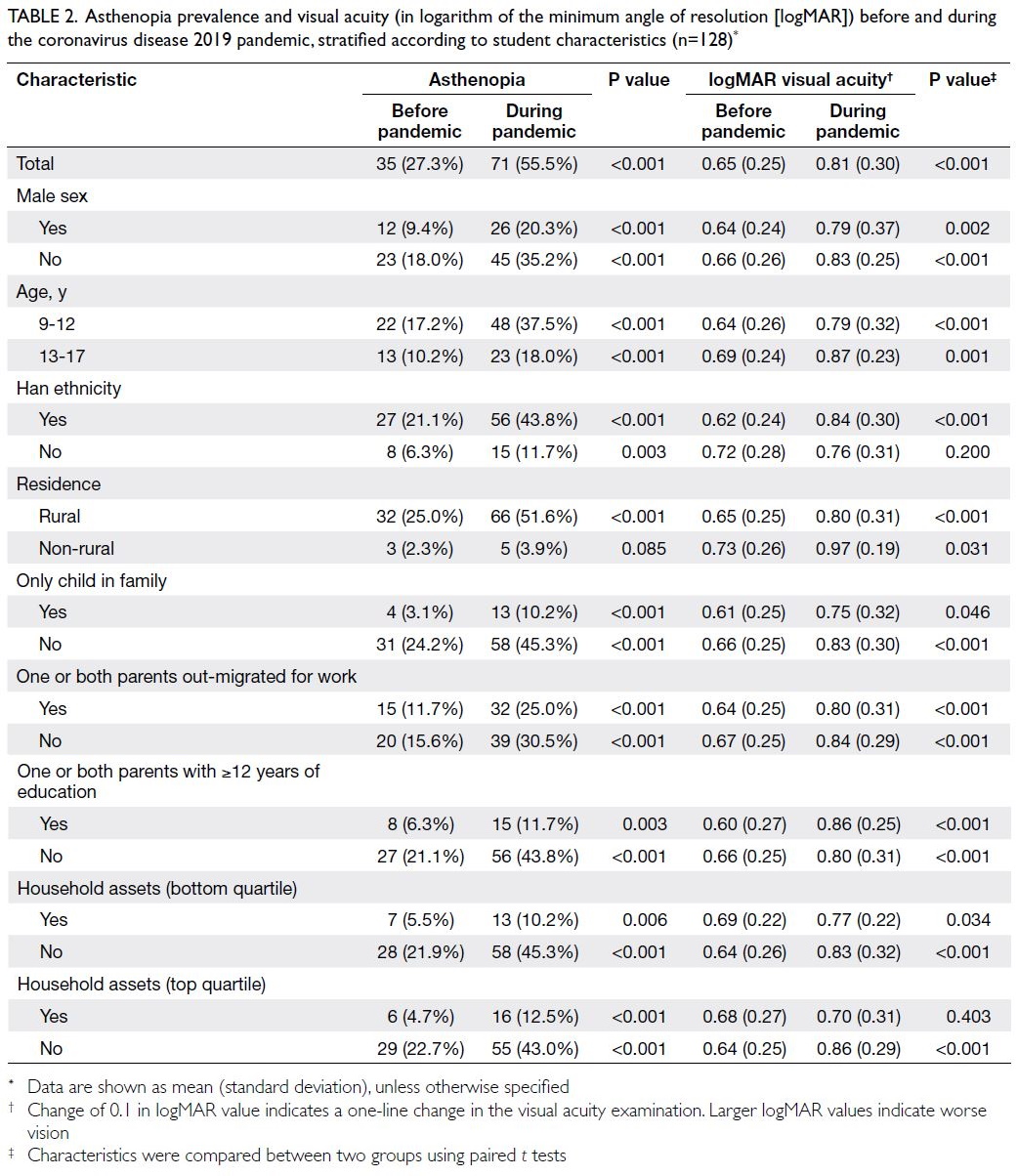

The prevalence of asthenopia and progression

of vision impairment significantly differed between

the pandemic and pre-pandemic periods. The

prevalence of asthenopia during the pandemic was

55% (71/128), whereas it was 27% (35/128) during the

pre-pandemic period (P<0.001). The mean logMAR VA was worse during the pandemic compared with

the pre-pandemic period (0.81 vs 0.65; P<0.001).

The prevalence of asthenopia was higher during the

pandemic than during the pre-pandemic period,

regardless of the characteristics used to stratify

participants. The mean logMAR VA was worse

during the pandemic than during the pre-pandemic

period, although the difference being insignificant

among participants with non-Han ethnicity and

participants in the top quartile of household assets

(Table 2).

Table 2. Asthenopia prevalence and visual acuity (in logarithm of the minimum angle of resolution [logMAR]) before and during the coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic, stratified according to student characteristics (n=128)

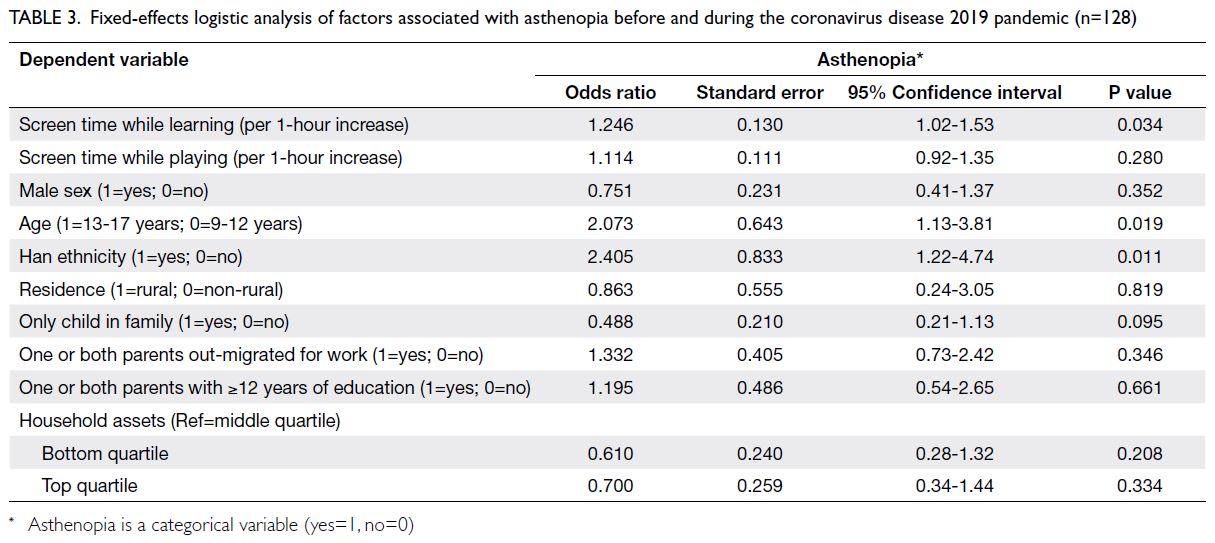

Fixed-effects logistic models for asthenopia revealed that screen time while learning was

associated with asthenopia prevalence, and the

probability of asthenopia increased by 24.6% for

each 1-hour increase in screen time while learning

(95% confidence interval [CI]=1.02-1.53; P=0.034).

Additionally, older age (odds ratio [OR]=2.073,

95% CI=1.13-3.81, P=0.019), Han ethnicity

(OR=2.405, 95% CI=1.22-4.74; P=0.011), and only-child

status (OR=0.488, 95% CI=0.21-1.13; P=0.095)

were factors associated with asthenopia; screen time

while playing was not (Table 3).

Table 3. Fixed-effects logistic analysis of factors associated with asthenopia before and during the coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic (n=128)

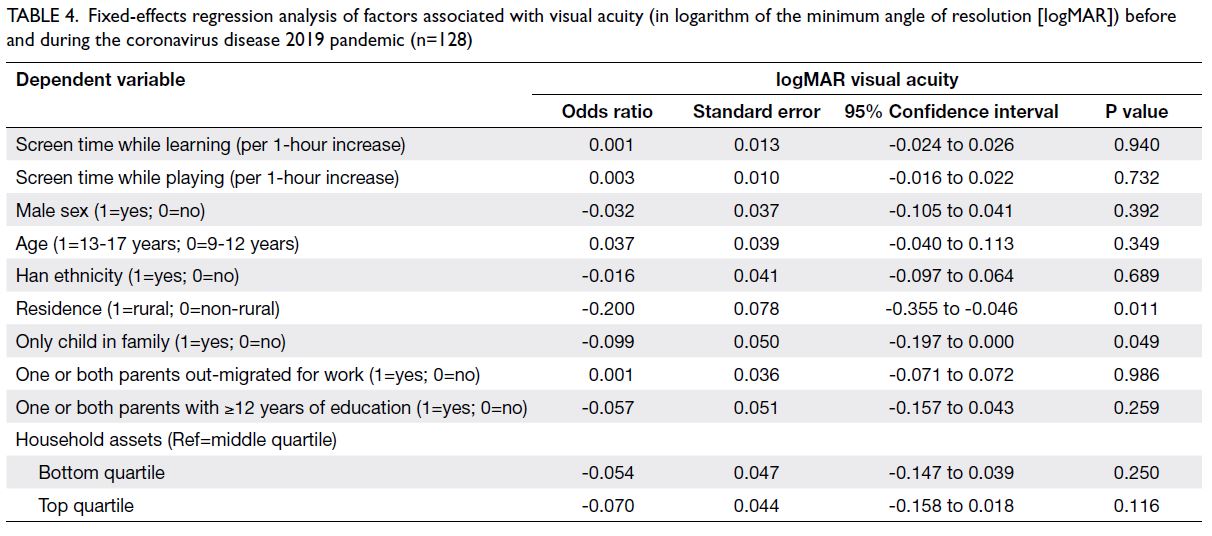

Fixed-effects regression models showed that residence in a non-rural area (OR=-0.200, 95%

CI=-0.355 to -0.046; P=0.011) and only-child status

(OR=-0.099, 95% CI=-0.197 to 0.000; P=0.049) were

factors associated with logMAR VA. The probability

of worse logMAR VA increased by 0.200 in non-rural

areas, compared with rural areas. However,

screen time while learning and screen time while

playing were not associated with vision impairment

(Table 4).

Table 4. Fixed-effects regression analysis of factors associated with visual acuity (in logarithm of the minimum angle of resolution [logMAR]) before and during the coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic (n=128)

Discussion

The global spread of the COVID-19 pandemic

has affected the education of >1.5 billion children

and adolescents worldwide.25 The participants in our study were representative of this important

population. They demonstrated declines in VA and

vision health during the pandemic, in relation to the

excessive use of digital devices; these findings were

consistent with the results of previous studies.19 26

All students in our study were attending online

classes during the pandemic. We observed an increase

in the mean daily time spent on digital devices

between the pre-pandemic and pandemic periods;

these results are consistent with international

findings that screen time was greater during the

pandemic than before the pandemic.19 Notably, we

found that total screen time and screen time while

learning significantly changed among rural students but not among non-rural students; these results

are also consistent with previous findings.19 This

difference presumably occurred because, compared

with rural students, non-rural students were more

likely to use digital devices and online classes before

the pandemic.

We observed a significant difference in

asthenopia prevalence among students in low-income

areas of western China before and during

the pandemic; this finding supports the results of

previous studies.26 27 Although the risk of asthenopia

reportedly increases with screen time,28 there

is no published literature concerning changes

in asthenopia among students in relation to the

COVID-19 pandemic. Similar to previous studies,14

we found that the prevalence of asthenopia was

approximately twofold greater among students aged

13 to 17 years than among those aged 9 to 12 years.

Furthermore, Moon et al26 reported that symptoms

of dry eye diseases were more common among

older children than among younger children. Older

children spend more time using digital devices,

leading to a higher prevalence of asthenopia.29

This study showed significant progression

of vision impairment in relation to the pandemic;

similarly, a study in eastern China revealed that

students had worse vision during the pandemic,

compared with their vision at pre-pandemic

examinations.4 However, screen time has not been

associated with vision impairment among students.

Furthermore, evidence regarding the impact of

digital devices use on vision impairment has been

inconsistent,30 31 with computer screen time made

students’ vision worse while television viewing

had no effect. We speculate that the association

will become clearer as school-aged children spend

increasing amounts of time using these devices.

This study had three important limitations.

First, the screen time data were retrospectively

collected through a self-reporting mechanism, which

may have led to recall bias. However, considering

the resource and measurement limitations that

researchers encountered during the pandemic, self-reported

recall was regarded as the optimal method

for collection of screen time data in the present

study. Second, the selection of students with poor

vision may lead to underestimation of screen time

effects on the general population, and the results

should be generalised with caution. Third, the study

was not designed to accurately distinguish between

vision impairment caused by intrinsic factors and

vision impairment caused by pandemic-related eye

strain.

Our findings provide new evidence regarding

the effects of increased screen time on asthenopia

and vision impairment among students in western

rural China during the pandemic; they can also serve

as a basis for future research. Although pandemic-related school closures are temporary, the increasing

popularity of online classes may accelerate the

overall acceptance of digital devices. The use of

online learning approaches is associated with

multiple vision problems, which merit attention in

future studies.

Conclusion

The present study demonstrated that asthenopia

and vision impairment among students in western

rural China were also affected by the pandemic;

these findings provide critical insights regarding

the effects of the pandemic on vision health in rural

students. Moreover, the findings highlight important

issues related to childhood vision health during the

pandemic; parents, teachers, and eye care providers

should consider evidence-based measures to avoid

asthenopia and vision impairment in children.

The current pace of economic and technological

development is leading to increased use of digital

devices and online learning approaches, but vision

problems in rural China have not received sufficient

consideration. Thus, there is a critical need for

greater efforts to monitor VA and vision health

among students in this region.

Author contributions

Concept or design: All authors.

Acquisition of data: Y Ding, H Guan, K Du.

Analysis or interpretation of data: Y Ding, H Guan, K Du, Y Shi.

Drafting of the manuscript: Y Ding, Y Zhang, Z Wang.

Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: H Guan, Y Shi.

Acquisition of data: Y Ding, H Guan, K Du.

Analysis or interpretation of data: Y Ding, H Guan, K Du, Y Shi.

Drafting of the manuscript: Y Ding, Y Zhang, Z Wang.

Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: H Guan, Y Shi.

All authors contributed to the study, approved the final version for publication, and take responsibility for its accuracy

and integrity.

Conflicts of interest

As an International Editorial Advisory Board member of the journal, Y Shi was not involved in the peer review process.

Other authors have disclosed no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgement

We thank Dr Wenting Liu, Dr Jiaqi Zhu, and staff from the Center for Experimental Economics in Education of Shaanxi

Normal University, China for their valuable contributions.

Funding/support

H Guan received funding for this study from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No.: 7180310)

and Soft Science Project of Shaanxi Province (Grant No.: 2023-CX-RKX-127). Y Ding received funding for this study from

the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities

(Grant No.: 2020CSWY018). This study was supported by the

111 Project (Grant No.: B16031). The funders had no role in

designing the study, collecting, analysing or interpreting the

data, or in drafting this manuscript.

Ethics approval

This study protocol was approved by Sun Yat-sen University,

China (Registration No.: 2013MEKY018) and all procedures

followed the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki.

Permission was obtained from the local boards of education

in the study area, as well as the principals of all participating

schools. All participating children provided oral assent before

baseline data collection, and legal guardians provided written

informed consent for their children to be enrolled in the study.

References

1. World Health Organization. WHO timeline—COVID-19. 2020. Available from: https://www.who.int/news-room/detail/27-04-2020-who-timeline---covid-19. Accessed 13 Sep 2021.

2. Li D, Liu Z, Liu Q, et al. Estimating the efficacy of quarantine and traffic blockage for the epidemic caused by 2019-nCoV (COVID-19): a simulation analysis. medRxiv [Preprint]. 25 Feb 2020. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.02.14.20022913. Accessed 13 Sep 2021. Crossref

3. Wang G, Zhang Y, Zhao J, Zhang J, Jiang F. Mitigate the effects of home confinement on children during the COVID-19 outbreak. Lancet 2020;395:945-7. Crossref

4. Wang J, Li Y, Musch DC, et al. Progression of myopia in school-aged children after COVID-19 home confinement. JAMA Ophthalmol 2021;139:293-300. Crossref

5. Kowalska M, Zejda JE, Bugajska J, Braczkowska B, Brozek G, Malińska M. Eye symptoms in office employees working at computer stations [in Polish]. Med Pr 2011;62:1-8.

6. Cumberland PM, Peckham CS, Rahi JS. Inferring myopia over the lifecourse from uncorrected distance visual acuity

in childhood. Br J Ophthalmol 2007;91:151-3. Crossref

7. Pascolini D, Mariotti SP. Global estimates of visual impairment: 2010. Br J Ophthalmol 2012;96:614-8. Crossref

8. Resnikoff S, Pascolini D, Mariotti SP, Pokharel GP. Global magnitude of visual impairment caused by uncorrected

refractive errors in 2004. Bull World Health Organ 2008;86:63-70. Crossref

9. Jan C, Li SM, Kang MT, et al. Association of visual acuity with educational outcomes: a prospective cohort study. Br

J Ophthalmol 2019;103:1666-71. Crossref

10. Roch-Levecq AC, Brody BL, Thomas RG, Brown SI. Ametropia, preschoolers’ cognitive abilities, and effects of

spectacle correction. Arch Ophthalmol 2008;126:252-8. Crossref

11. Zhang Z, Xu G, Gao J, et al. Effects of e-learning environment use on visual function of elementary and middle school

students: a two-year assessment—experience from China.

Int J Environ Res Public Health 2020;17:1560. Crossref

12. Wong CW, Tsai A, Jonas JB, et al. Digital screen time during COVID-19 pandemic: risk for a further myopia boom? Am J Ophthalmol 2021;223:333-7. Crossref

13. Kim J, Hwang Y, Kang S, et al. Association between sexposure to smartphones and ocular health in adolescents.

Ophthalmic Epidemiol 2016;23:269-76. Crossref

14. Mohan A, Sen P, Shah C, Jain E, Jain S. Prevalence and risk factor assessment of digital eye strain among children

using online e-learning during the COVID-19 pandemic:

digital eye strain among kids (DESK study-1). Indian J

Ophthalmol 2021;69:140-4. Crossref

15. Guan H, Yu NN, Wang H, et al. Impact of various types of near work and time spent outdoors at different times of day on visual acuity and refractive error among Chinese school-going children. PLoS One 2019;14:e0215827.Crossref

16. Sultana A, Tasnim S, Hossain MM, Bhattacharya S,

Purohit N. Digital screen time during the COVID-19

pandemic: a public health concern. Available from: https://f1000research.com/articles/10-81. Accessed 13 Sep 2021. Crossref

17. Nigg CR, Wunsch K, Nigg C, et al. Are physical activity,

screen time, and mental health related during childhood,

preadolescence, and adolescence? 11-year results from

the German Montorik–Modul Longitudinal Study. Am J

Epidemiol 2021;190:220-9. Crossref

18. Schmidt SC, Anedda B, Burchartz A, et al. Physical activity

and screen time of children and adolescents before and

during the COVID-19 lockdown in Germany: a natural

experiment. Sci Rep 2020;10:21780. Crossref

19. Aguilar-Farias N, Toledo-Vargas M, Miranda-Marquez S,

et al. Sociodemographic predictors of changes in physical

activity, screen time, and sleep among toddlers and

preschoolers in Chile during the COVID-19 pandemic. Int

J Environ Res Public Health 2020;18:176. Crossref

20. Bates LC, Zieff G, Stanford K, et al. COVID-19 impact on behaviors across the 24-hour day in children and

adolescents: physical activity, sedentary behavior, and

sleep. Children (Basel) 2020;7:138. Crossref

21. National Bureau of Statistics of China, PRC Government. China Statistical Yearbook 2020. Available from: http://www.stats.gov.cn/tjsj/ndsj/2020/indexch.htm. Accessed 14

Sep 2021.

22. National Bureau of Statistics of China, PRC Government. China Statistical Yearbook 2013. Beijing, China: China

State Statistical Press; 2013.

23. Seguí Mdel M, Cabrero García J, Crespo A, Verdú J, Ronda E. A reliable and valid questionnaire was developed to measure computer vision syndrome at the workplace. J Clin Epidemiol 2015;68:662-73. Crossref

24. Yi H, Zhang L, Ma X, et al. Poor vision among China’s rural primary school students: prevalence, correlates and

consequences. China Econ Rev 2015;33:247-62. Crossref

25. United Nations International Children’s Emergency Fund.

Don’t let children be the hidden victims of COVID-19

pandemic. Available from: https://www.unicef.org/press-releases/dont-let-children-be-hidden-victims-covid-19-pandemic. Accessed 6 Oct 2020.

26. Moon JH, Kim KW, Moon NJ. Smartphone use is a risk factor for pediatric dry eye disease according to region and

age: a case control study. BMC Ophthalmol 2016;16:188. Crossref

27. Moon JH, Lee MY, Moon NJ. Association between video display terminal use and dry eye disease in school children.

J Pediatr Ophthalmol Strabismus 2014;51:87-92. Crossref

28. Rechichi C, De Mojà G, Aragona P. Video game vision syndrome: a new clinical picture in children? J Pediatr

Ophthalmol Strabismus 2017;54:346-55.Crossref

29. Mowatt L, Gordon C, Santosh AB, Jones T. Computer vision syndrome and ergonomic practices among undergraduate

university students. Int J Clin Pract 2018;72:e13035. Crossref

30. Terasaki H, Yamashita T, Yoshihara N, Kii Y, Sakamoto T. Association of lifestyle and body structure to ocular axial

length in Japanese elementary school children. BMC

Ophthalmol 2017;17:123. Crossref

31. Fernández-Montero A, Olmo-Jimenez JM, Olmo N, et al. The impact of computer use in myopia progression: a

cohort study in Spain. Prev Med 2015;71:67-71. Crossref