© Hong Kong Academy of Medicine. CC BY-NC-ND 4.0

REMINISCENCE: ARTEFACTS FROM THE HONG KONG MUSEUM OF MEDICAL SCIENCES

Death certificate and death registration in

Hong Kong

TW Wong, FHKAM (Emergency Medicine); Moira Chan-Yeung, FRCP, FRCPC

Members, Education and Research Committee, Hong Kong Museum of Medical Sciences Society

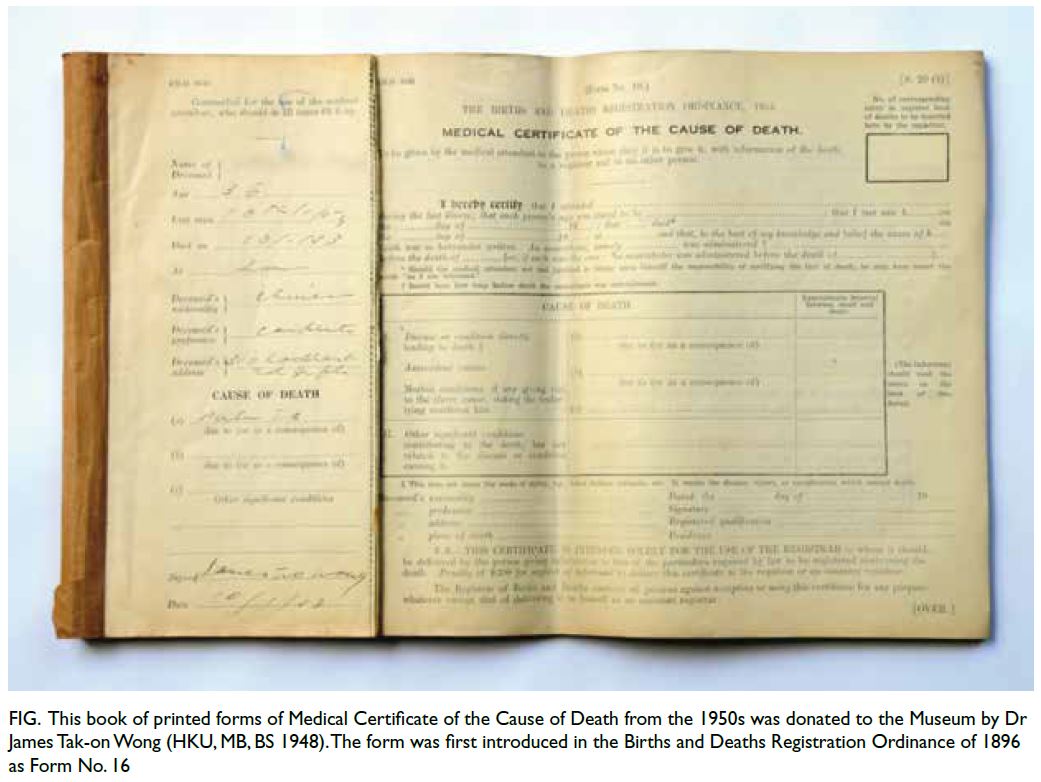

All medical doctors in Hong Kong are familiar with

the death certificate (Fig). Many of us have signed

this form as a matter of course without thinking

about how the death certificate came about, but it

has an interesting early history.

Figure. This book of printed forms of Medical Certificate of the Cause of Death from the 1950s was donated to the Museum by Dr James Tak-on Wong (HKU, MB, BS 1948). The form was first introduced in the Births and Deaths Registration Ordinance of 1896 as Form No. 16

Hong Kong became a British Colony in 1842.

In the early 1830s, the British Parliament recognised

the need for accurate records for the purposes of

voting, planning, taxation, and defence. In 1837,

legislation was passed to create a civil registration of

births, marriages, and deaths in England and Wales

and of British subjects living abroad.

In Hong Kong, although the total population,

births and deaths had been reported every year since

the colony was established, the information was inaccurate because of the lack of a census for birth

and death registration. A census once every 10 years

was carried out only after 1881. The border between

China and Hong Kong was porous and people could

travel readily between the two. During festivals

or certain events such as the plague epidemic of

1894, half of the Chinese population of the colony

disappeared to the Mainland. The Chinese had

resisted registration of any kind for fear of taxation.

Despite urging by the British Government, the

colonial administration did not establish birth and

death registration, partly because they did not

wish to upset the Chinese and partly because it

was costly to establish the infrastructure for such

registration. The colonial administration also failed to provide official cemeteries for the Chinese until the 1870s.1

In 1872, unable to delay any longer, the Hong

Kong Government enacted the Births and Deaths

Registration Ordinance (No. 7 of 1872) that required

all births to be registered within 7 days and all

deaths within 5 days. The Registrar General acted

as the Chief Registrar of Births and Deaths, assisted

by district registrars who were police officers in

different districts in Victoria and Kowloon. Burial

could take place only after a valid death certificate

had been obtained.2

An essential component of the death certificate

was the cause of death, because it facilitated early

identification of infectious disease epidemics. The

1872 Ordinance required an individual who was

present at the death or in attendance during the

illness or the occupier or a tenant of the house of the

deceased to provide the particulars of the death. In

some cases, the Registrar might request an enquiry

by the Coroner and the death certificate would be

issued only after the Registrar was satisfied with

the cause of death as reported by the Coroner.

Nonetheless there was no mention of a post-mortem

examination. In addition, some individuals were

buried without reporting to the Registrar; many

Chinese would return to their native village to die

when they developed a severe illness. For these

reasons, and despite the 1872 Ordinance, stated

cause of death was often inaccurate and the number

of deaths among Chinese was underestimated.3

In 1888, the Magistrates (Coroners Powers)

Ordinance was enacted wherein Coroners were

abolished and their duties assumed by magistrates.4

The Ordinance empowered the Governor in

Council to make rules for regulating the practice

and procedures for post-mortem enquiries and

examinations. When a dead body was brought to a

hospital, the medical officer in charge of the hospital,

government medical officer or deputised registered

medical practitioner would carry out a preliminary

external examination of the body and report in

writing to the magistrate who might, if he deemed

necessary, order an autopsy.

Autopsy had been performed prior to 1888

but very rarely among the Chinese in Hong Kong

or in China because of the Chinese deep-seated

aversion to autopsy and belief that it was a crime.5

Nevertheless in 1865, autopsies were carried out on

prisoners who died following specific outbreaks in

Victoria Gaol or from a fever of unknown origin.6

Autopsies were gradually accepted by the people in

Hong Kong for pragmatic reasons. After the plague

epidemic, public health practice required that the

belongings of a person suspected to have died from

the plague be ‘sanitised’ by burning to prevent the

spread of infection. If death was confirmed not to be

due to plague, the patient’s belongings and property could be kept and not burned. This provided an

incentive for autopsy. The 1888 Ordinance required

the cause of death to be determined when it was not

known although there were still no proper facilities

for post-mortem examination.

Another Births and Deaths Registration

Ordinance was passed in 18967 when the general

Register Office was transferred to the Sanitary

Department with the duties of the Registrar of

Births and Deaths now performed by the Head of the

Sanitary Department. The district registers of births

and deaths were still kept at police stations and the

officers in charge of these stations and the principal

clerk at every public dispensary were appointed

as assistant registrars for the district. In 1897, the

government appointed Dr Francis William Clark as

the first Medical Officer of Health. His role included

assisting the Registrar to ascertain cause of death.8

In 1907, the first two public mortuaries were

established, one in Hong Kong and one in Kowloon,

where post-mortem examinations could be carried

out. Additionally, Governor Frederick Lugard

appointed Dr Earnest Albert Shaw and Dr John

Christopher Thomson as medical officers. They were

required to perform an autopsy and determine cause

of death for any individual who had died suddenly

or by accident or violence, or under suspicious

circumstances within the colony or had been brought

into the colony.9

Although the 1896 Ordinance indicated that

the principal clerk of the district public dispensary

in addition to the district police officer could serve

as assistant registrar for births and deaths, there

was no public dispensary until later on. The first

two public dispensaries financed by the government

were established in Wan Chai and Tai Po in the late

1890s (probably in 1899). The one in Wan Chai was

short-lived, closing in 1903. Nonetheless from 1906

until just before World War II, about 10 Chinese

Public Dispensaries were established and financed

by the Chinese elite, initially with the main purpose

of reducing the number of ‘dumped bodies’ in the

streets. During the plague of 1894, harsh laws

required the home of the deceased to be thoroughly

sanitised with whitewash, the furniture put into a

large tank of disinfectant and contacts quarantined.

As a result, patients were often left in the streets

to die or dumped in the streets after their death.

The Chinese Public Dispensaries were staffed by

licentiates of the Hong Kong College of Medicine

who were not allowed to practise in Hong Kong

because their inadequate training (including lack of

autopsy experience) barred them from registration

under the Medical Registration Ordinance. Their

main duty was to determine the cause of death of

the dumped bodies but later, other duties were

added including registration of births and deaths,

treatment of patients and vaccinations.10 In 1908, they were authorised to sign death certificates for the first time.11

In 1887, Dr John Mitford Atkinson, who

became the superintendent of the Government Civil

Hospital, adopted the International Classification

of Diseases that enabled the mortality of various

diseases to be compared with other populations and the effects of intervention on the same population

to be assessed.12 Thus, by 1908, death registration in

Hong Kong was more effective and backed by proper

ordinances and enforcement as well as autopsy

facilities. Statistics became more useful because of

standardisation of diagnoses of diseases but further

improvement was still necessary.

References

1. Tam C. Death in Hong Kong: managing the dead in a colonial city from 1841 to 1913 [thesis]. Hong Kong: The

University of Hong Kong; 2018.

2. Births and Deaths Registration Ordinance, No 7 of 1872, The Hong Kong Government Gazette, 27 July 1872.

3. The China Mail, 1879-04-30. 5 June 1879. Available from: https://mmis.hkpl.gov.hk/coverpage/-/coverpage/view?p_r_p_-1078056564_c=QF757YsWv5%2BzBV%2Fmy%2B7fMAilSsNss%2Bug&_coverpage_WAR_mmisportalportlet_o=0&_coverpage_WAR_mmisportalportlet_actual_q=%28%20all_dc.title%3A%28%22China%5C%20Mail%22%29%29%20AND+%28%20%28%20-all_dc.title%3A%28%E9%A6%99%E6%B8%AF%E8%8F%AF%E5%AD%97%29%29%29%20AND+%28%20verbatim_dc.collection%3A%28%22Old%5C%20HK%5C%20Newspapers%22%29%29&_coverpage_WAR_mmisportalportlet_sort_order=desc&_coverpage_WAR_mmisportalportlet_sort_field=dc.publicationdate_bsort&_coverpage_WAR_mmisportalportlet_log=Y&_coverpage_WAR_mmisportalportlet_freetext_filter=1879-04-30&_coverpage_WAR_mmisportalportlet_filter=dc.publicationdate_dt%3A%5B*+TO+1900-01-01T00%3A00%3A00Z%5D . Accessed 27 Sep 2021.

4. Magistrates (Coroners Powers) Ordinance, 1888, Historical Laws of Hong Kong. Available from: https://oelawhk.lib.hku.hk/items/show/1661. Accessed 27 Sep 2021.

5. Beh PS, Wu HY. The porcelain autopsy table and early post-mortem examinations in Hong Kong. Hong Kong Med J

2018;24:434-5.

6. Colonial Surgeon’s Report with Returns on the Sanitary Conditions of the Colony for the Year 1865. The Hong Kong Government Gazette, 17 March 1866.

7. Births and Deaths Registration Ordinance, No. 7 of 1896, The Hong Kong Government Gazette, 11 August 1896.

8. Government Notification No 299, The Hong Kong Government Gazette, 24 July 1897.

9. Appointments no 663, The Hong Kong Government Gazette, 22 October 1907.

10. Chan-Yeung M. A Medical History of Hong Kong: The Development and Contributions of Outpatient Services.

Hong Kong: The Chinese University of Hong Kong Press; 2021: 14-6. Crossref

11. Chinese Medical Practitioners trained in Western Medical Sciences authorized to grant death certificates. The Hong Kong Government Gazette, 10 July 1908.

12. Chan-Yeung M. A Medical History of Hong Kong 1842-1941. Hong Kong: The Chinese University of Hong Kong

Press; 2018: 246. Crossref