Hong Kong Med J 2022 Aug;28(4):306–14 | Epub 8 Aug 2022

© Hong Kong Academy of Medicine. CC BY-NC-ND 4.0

ORIGINAL ARTICLE (Healthcare in Mainland China)

Utilisation of village clinics in Southwest China:

evidence from Yunnan Province

Y Shi, PhD1; S Song, MA1; L Peng, MA1; J Nie, PhD1; Q Gao, PhD1; H Shi, PhD2; DE Teuwen, MD3; H Yi, PhD4,5

1 Center for Experimental Economics in Education, Shaanxi Normal University, Xi’an, China

2 Business Department Center of Red Cross Society of China, Beijing, China

3 Ghent University Hospital, Department of Neurology, Ghent, Belgium

4 China Center for Agricultural Policy, School of Advanced Agricultural Sciences, Peking University, Beijing, China

5 Institute for Global Health and Development, Peking University, Beijing, China

Corresponding author: Dr Q Gao (gqiufeng820@163.com)

Abstract

Introduction: Primary healthcare in rural China

is underutilised, especially in village clinics in

Southwest China. The aim of this study was to

explore any relationships among the ethnicity of

the healthcare provider, the clinical competence of

the healthcare provider, and the utilisation of village

clinics in Southwest China.

Methods: This cross-sectional survey study

involved 330 village healthcare providers from three

prefectures in Yunnan Province in 2017. Multiple

logistic regressions were adopted to investigate the

utilisation of primary healthcare among different

ethnic healthcare providers.

Results: Primary healthcare utilisation was higher in

village clinics where healthcare providers were Han

Chinese than those where healthcare providers were

ethnic minority (151 vs 101, P=0.008). The logistic

regression analysis showed that clinical competence

was positively associated with the utilisation

of primary healthcare (odds ratio [OR]=1.49,

95% confidence interval [CI]=1.12-2.00; P=0.007)

and that inadequate clinical competence of ethnic

minority health workers may lead to a lag in

the utilisation of primary healthcare (OR=0.45,

95% CI=0.23-0.89; P=0.022).

Conclusion: Our results confirm differences in the utilisation of primary healthcare in rural Yunnan Province among healthcare providers of different

ethnicities. Appropriate enhancements of clinical

competence could be conducive to improving the

utilisation of primary healthcare, especially among

ethnic minority healthcare providers.

New knowledge added by this study

- The results of our study confirmed that differences exist in the utilisation of primary healthcare in rural Yunnan Province among different ethnic minority healthcare providers.

- Significant differences in clinical competence were observed between ethnic minority and Han Chinese majority healthcare providers.

- The underdeveloped clinical competence of ethnic minority healthcare providers likely contributes to the difference in utilisation of village clinics.

- Proper enhancements for ethnic minority providers could be conducive to improving their clinical competence.

- More involvement from the government and adequate in-service training for ethnic minority healthcare providers could help improve the utilisation of primary healthcare.

Introduction

For rural residents, who account for approximately

41% of China’s population, primary healthcare is

the main source of medical care.1 To meet their

healthcare needs, China promoted a tiered medical

system in 2015 to encourage people to fully utilise

primary healthcare.2 3 Nevertheless, while the government invests various resources, primary

healthcare in rural areas remains underused.4 5 6

From 2015 to 2018, the total number of out-patient

visits in rural primary healthcare institutions

decreased from 2.90 billion to 2.70 billion, while the

number of hospital visits increased from 3.10 billion

to 3.60 billion.7

Disparity exists in the utilisation of primary

healthcare across different regions of China.

Compared with rural residents in eastern China,

the utilisation of primary healthcare among those in

western China is relatively low.8 9 The lack of medical

resources and sparseness of the land in western

China contributes to the inconvenience of accessing

primary healthcare among rural residents.10 11 12 In

addition to the difference between eastern and

western China, differences in the utilisation of

primary healthcare exists among the provinces

in western China.11 Although many studies have

reported on the utilisation of primary healthcare

in Southwest China, most have focused on the

perspective of rural residents while neglecting the

importance of providers, who play important

roles in primary healthcare.3 4 Therefore, research

concerning village healthcare providers in Southwest

China could be conducive to understanding the

utilisation of primary healthcare.

Southwest China is home to more ethnic

minority village healthcare providers than other

areas in China.11 To investigate village healthcare

providers in Southwest China, the ethnicity of

providers, which may be linked to the utilisation

of healthcare, is a factor that cannot be ignored.

Previous studies have illustrated that ethnic minority

providers are more likely to attract patients from the

same ethnicity, and this finding has been attributed

to the patients’ preference instead of the capability of

minority providers.13 14 Existing studies were mainly conducted outside China or were related to providers

who performed traditional Chinese medicine.13 14 15

Therefore, knowledge regarding whether differences

exist in the utilisation of primary healthcare among

Chinese ethnic minority providers and Han Chinese

majority providers is limited.

Clinical competence may influence the

utilisation of healthcare and serves as a practical

way to measure a doctor’s working performance

and quality.16 17 Some studies in China have shown

that the ethnicity of medical students might be

related to their future clinical competence.18 19 20 21 22

Studies conducted in Southwest China confirmed

the underdeveloped clinical competence of village

providers, but most studies failed to distinguish the

ethnicity of the healthcare providers.23 24 25 26 Whether

ethnic minority healthcare providers in rural areas

of China have underdeveloped clinical competence

remains unclear.

Considering the above, the purpose of the

present study was to investigate the utilisation of

primary healthcare in western China. In particular,

the aims were to clarify whether the ethnicity of

healthcare providers affects utilisation of primary

healthcare; whether there are differences in clinical

competence among different ethnic groups; and

whether clinical competence of healthcare providers

affects utilisation of primary healthcare.

Methods

Study design, setting and sampling method

This study was a cross-sectional survey conducted

in three prefectures (ie, prefecture-level cities) in

Yunnan Province, an economically developing area

in Southwest China. In 2017, the per capita gross

domestic product in Yunnan Province was US$5068,

which is lower than the national average (US$8777).27

The total population in Yunnan Province was

47.71 million, and the proportion of the rural

population in Yunnan Province was 53.31%, which

is much higher than the overall proportion of rural

population in China (41.48%).27 The three prefectures

included in our study have a total rural population of

6.50 million, accounting for 20.00% of the total rural

population in Yunnan Province.

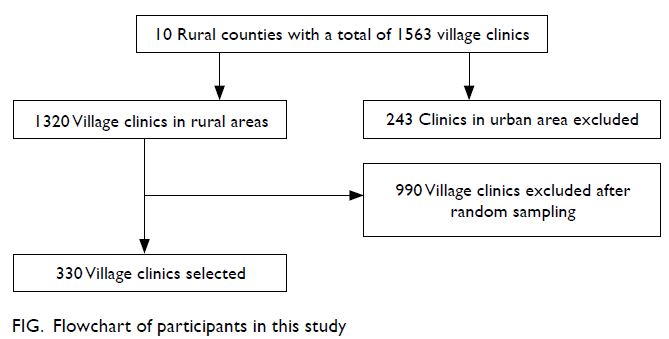

To investigate the utilisation of primary

healthcare in rural China, we conducted a cross-sectional

study in 330 village clinics (VCs),

representing the first tiers of China’s three-tiered

rural health system.4 In summary, we selected a

random sample of 330 healthcare providers from

three prefectures in three steps (Fig). First, we

selected 10 counties (in three prefectures) at random,

after excluding three urban counties and 13 counties

with a minority population greater than 20%. Second,

we used probability proportional to size sampling to

randomly select 330 VCs proportional to the number of VCs in each county. Finally, we asked each clinic

to list all staff serving in the clinic and describe their

responsibilities. Considering the measurement of

different types of medical practitioners, we excluded

healthcare providers other than Western medicine

practitioners (ie, traditional Chinese medicine

practitioners or those responsible for public health

services only). Then, we randomly selected one of

the remaining village healthcare providers as our

sample.

Data collection

The data collection was carried out in July 2017 by trained investigators. The survey consisted of a

clinic form administered to the head of the VC and

a clinician form administered to providers in each

clinic verbally.

The clinic form (Supplementary Table 1)

was used to collect basic information regarding the

VCs, including the number of equipment per clinic,

whether the drugs sold by the clinics met the zero

price difference of medicine (a policy requires no

mark-ups above the cost of drugs),6 the number of

clinics within 5 km, the number of out-patient visits

per clinic, and the number of providers per clinic.

The clinician form (Supplementary Table 2) consisted of two parts. The first part was

used to obtain information regarding the provider’s

demographics, working time allocation and

income. This part included age, sex, ethnicity, basic

salary, local residence (whether he/she was born

and raised in the sample village), and time spent

performing public health services. The second part

was used to obtain detailed information on the

providers’ in-service training participation in 2016

(the year before the survey year) and their clinical

competence, including education level, certificate in

rural medicine or higher, length of experience, and

medical study.

Assessment of the utilisation of village clinics

The primary healthcare system provides generalist clinical care and basic public health services.1 China

has promoted the three-tiered healthcare system

to improve the use of primary healthcare. In rural

China, the three-tiered healthcare system consists of

VCs, township health centres, and county hospitals.

Township health centres and VCs play a role in

primary healthcare, and VCs mainly provide out-patient

services under common clinical conditions.

To assess the utilisation of VCs, the investigators

asked the heads of the VCs to estimate (on average)

the total number of out-patient visits during the

previous month. The utilisation of the VCs was

calculated using data related to the total number

of out-patient visits, intramuscular injection visits,

intravenous infusion visits, and number of healthcare providers in the clinics. Specifically, the utilisation of

VCs in our research is measured on a per-provider

basis. Thus, the utilisation of VCs equals the total

number of out-patient visits divided by the number

of healthcare providers.

Measurement of the providers’ clinical

competence

Providers’ clinical competence is the quality

of healthcare providers pertaining to medical

knowledge, treatment quality, medical experience,

medical study background, and medical training.28

In our study, we evaluated the providers’ clinical

competence in the following dimensions: education

above college level (measured medical knowledge);

attainment of certificates in rural medicine or higher

(measured treatment quality); length of experience

(measured medical experience); participation

in medical studies (measured medical study

background); and completion of in-service training

(measured medical training).

In clinical competence, multiple characteristics

are often correlated; multicollinearity is a limitation

of applying a multiple logistic regression analysis

to measure clinical competence. A principal

component analysis is often used to address this issue

by transforming the data into one or two dimensions

that serve as a summary of the characteristics, such

as constructing an index.29 Therefore, we constructed

the Clinical Competence Index to assess the overall

clinical competence of the providers using a principal

component analysis approach.

Statistical methods

To explore the relationships between the healthcare providers and the utilisation of VCs, we used a

multiple logistic regression. We conducted three

types of regressions, and the outcome variable was

out-patient visits per doctor. In the first regression,

we measured the relationship between the village

providers’ ethnicity and the utilisation of VCs. In the second regression, we included only the variables

measuring the providers’ clinical competence. This

relationship might vary across different ethnicities,

and a heterogeneity analysis is needed. In the third

regression, we performed a heterogeneity analysis by

including the interaction term ‘Clinical Competence

Index ethnic minority providers’ to measure the

providers’ clinical competence and its relationship

with the utilisation of VCs across different ethnicities.

In each regression mentioned above, we

assessed the correlations with a fixed set of facility-level

and provider-level characteristics. These

characteristics included the number of equipment

per clinic, whether the drugs sold by the clinics met

the zero price difference of medicine, the number

of clinics within 5 km, the percentage of minority

residents in the town, the providers’ sex, salary,

local residency, and time spent providing public

health services. Notably, in all regressions, we also

controlled for county-fixed effects.

All statistical analyses were performed using

Stata version 15.0 statistical software (Stata Corp,

College Station [TX], United States). The results

with a P value <0.05 were considered statistically

significant.

Results

Characteristics and the utilisation of village

clinics

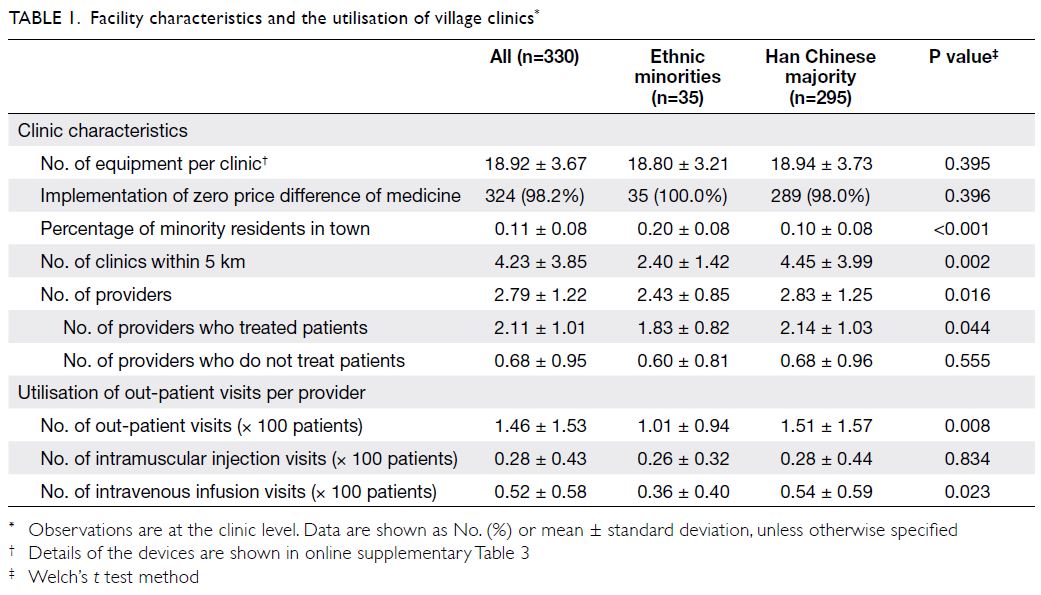

The questionnaire surveys were sent to 330 VCs

and 330 healthcare providers, and valid results

were obtained from all (participation rate 100%).

There were no significant differences in terms of the amount of clinic equipment (P=0.395) and

the implementation of the zero price difference

of medicine (P=0.396) among the VCs (Table 1).

However, the proportion of minority residents in

the towns significantly differed with type of VCs

(P<0.001). We also found that VCs where Han

Chinese providers worked faced more competition,

as the number of clinics within 5 km of these clinics

was significantly higher than that for clinics where

ethnic minority providers worked (P=0.002). The

average number of healthcare providers in the VCs

was 2.79. There was a significant difference in the

number of providers across clinics (P=0.016), and

this difference was mainly due to the number of

providers who treat patients (P=0.044). Among the

330 VCs, mean number of out-patient visits per

doctor was 146. The results indicate that the Han

Chinese providers conducted a significantly higher

average number of out-patient visits than the ethnic

minority providers (151 vs 101; P=0.008) [Table 1].

In addition, we documented intramuscular injection

visits and intravenous infusion visits. There was also

a significant difference between the ethnic minority

and Han Chinese majority providers in intravenous

infusion visits (P=0.023), but no significant

difference was found in intramuscular injection

visits (P=0.834).

Characteristics of the providers and their

clinical competence

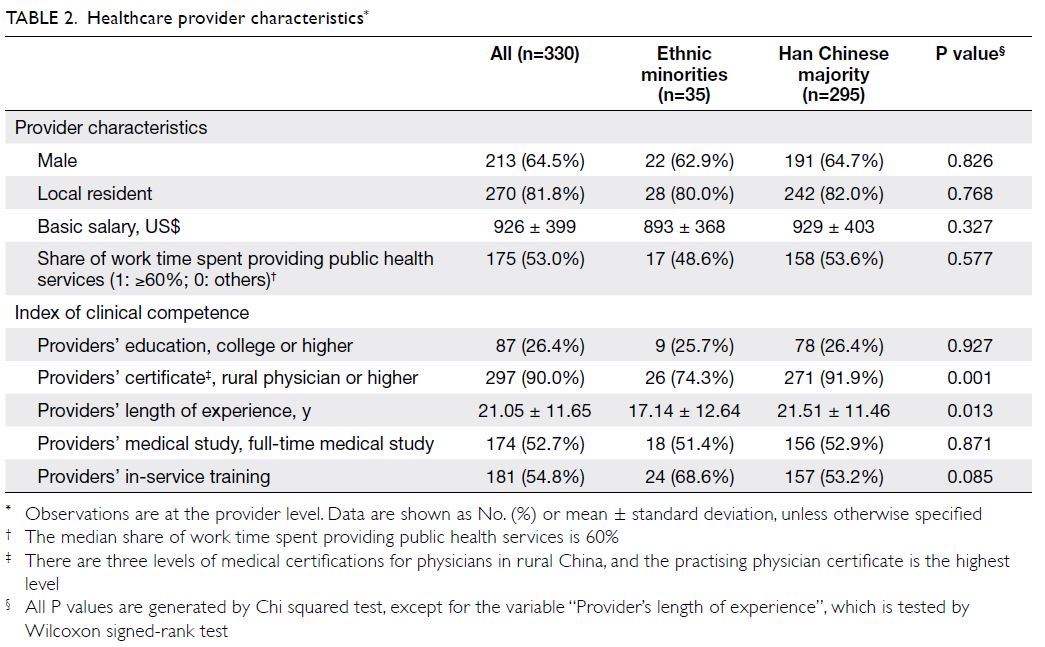

Most healthcare providers were male (64.5%), and 81.8% of providers were local residents (Table 2).

The mean ± standard deviation annual salary of

all providers was US$926±399, with no significant difference between the ethnic minority and Han

Chinese majority providers (P=0.327). More than

half of the healthcare providers devoted close to

60% of their work time to providing public health

services (P=0.577).

Among the 330 providers, 26.4% had a college

degree or higher, and the proportion among the Han

Chinese providers was similar to that (26.4%) among

the ethnic minority providers (25.7%, P=0.927)

[Table 2]. In total, 91.9% of the Han Chinese

providers were confirmed to have at least certificates

in rural medicine; however, the proportion was 74.3%

among the ethnic minority providers (P=0.001).

In addition, the length of experience of the Han

Chinese providers was significantly higher than

that of the ethnic minority providers (P=0.013). The

proportion of full-time medical studies conducted

by all providers was 52.7%, and more ethnic minority

providers than Han Chinese providers received in-service

medical training (P=0.085).

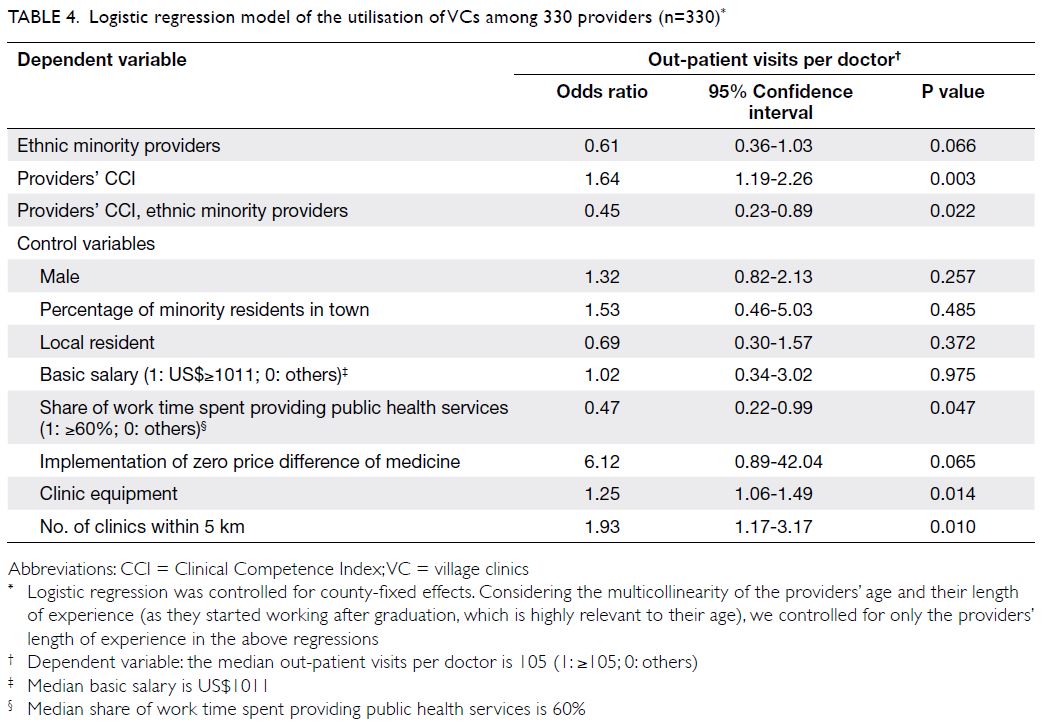

Determinants of the utilisation of village

clinics

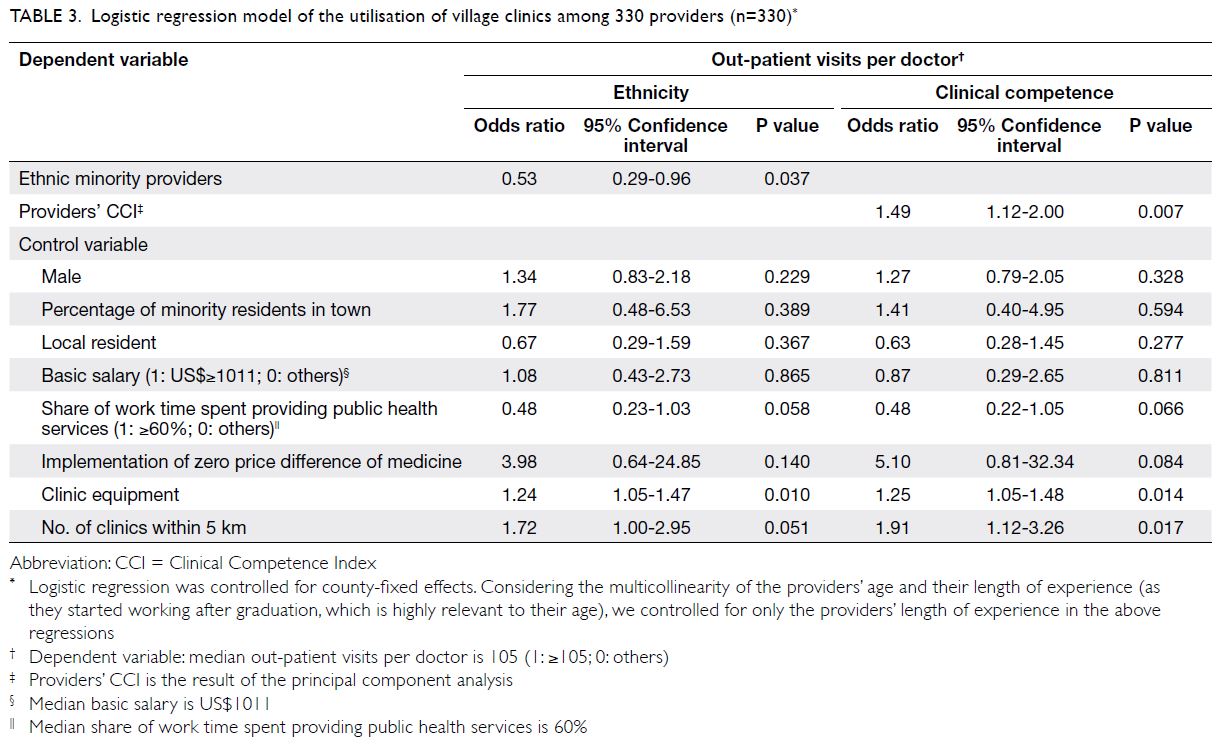

The ethnicity of the providers was negatively

associated with the utilisation of VCs (odds ratio

[OR]=0.53, 95% confidence interval [CI]=0.29-0.96;

P=0.037) [Table 3]; the providers’ clinical competence

was positively associated with the utilisation of VCs

(OR=1.49, 95% CI=1.12-2.00; P=0.007) [Table 3]. To

better examine this relationship, we performed a

heterogeneity analysis (Table 4). The results suggest that ethnic minority providers were likely to have

underdeveloped clinical competence, which could

further limit the utilisation of VCs (OR=0.45, 95%

CI=0.23-0.89; P=0.022) [Table 4]. We also measured

the determinants of intravenous infusion visits,

and the results suggest that the providers’ clinical

competence (OR=1.43, 95% CI=1.16-1.77; P=0.001)

[Supplementary Table 4] was associated with

the utilisation of VCs.

Table 3. Logistic regression model of the utilisation of village clinics among 330 providers (n=330)

Discussion

The data enabled an analysis of the utilisation of

primary healthcare in rural areas in Southwest

China. In general, there are three key findings in

this study. First, we found significant differences

between Han Chinese and ethnic minority providers

in the utilisation of VCs. Second, compared with

Han Chinese providers, ethnic minority providers in

our sample had poorer clinical competence in two

dimensions (possession of rural physician certificate

or length of experience). Finally, our results indicate

that underdeveloped clinical competence is a factor

responsible for the lower utilisation of VCs among

ethnic minority providers.

Our survey data show that the average number

of out-patient visits in the sampling VCs is 146 per

month per doctor, which is lower than the number of

out-patient visits in eastern China (188 per month per

doctor, 2017).9 Consistent with previous studies, we

believe that the inconvenience of accessing primary

healthcare among rural residents contributes to this difference.23 Compared with Yunnan Province

(116 per month per doctor, 2017), the utilisation

of VCs in the sampling area was higher.9 Based on

our investigation, the high utilisation of VCs in

the sampling area could be explained by both the

population density and local economic development.

According to the China Statistical Yearbook, the

rural residents in the three prefectures we studied

accounted for 20.00% of the total rural residents in

Yunnan Province, which is quite large compared

with the rate in other regions.30 The gross domestic

product of the sampling area is also relatively high in

Yunnan Province.27

However, the number of out-patient visits to

VCs where the main providers are ethnic minorities

is significantly lower than that of VCs where the main

providers are Han Chinese individuals. Previous

studies have shown that patients visiting providers of

their own race were more satisfied and deliberately

chose providers of their own race because of personal

preference and language issues.13 14 In contrast

to these studies, we excluded the preference and

language issues of patients. First, their studies were

generally conducted in large hospitals with many

providers, but the average number of providers in

our sampled VCs was approximately two, limiting the

patients’ choices. Second, regarding language, most

(81.8%) providers in our study were local residents

who were fluent in the local dialect. These providers

rarely have communication problems with their

patients. After the above exclusions, an investigation

of the characteristics of different ethnic providers

was performed. Consistent with previous studies,

there was no significant difference in provider

characteristics and income, and the amount of

clinic equipment and implementation of zero price

difference of the medicine did not differ.19 20

Furthermore, we find significant differences

between ethnic minority and Han Chinese village

providers in their clinical competence. As a crucial

aspect of primary healthcare services in rural China,

village providers are obligated to provide qualified

medical services, which require abundant clinical

competence.31 32 However, based on our evidence,

even if rural patients in Southwest China were asked

to follow the instructions of policymakers and seek

care primarily in VCs, they would visit higher-level

facilities with a relatively high cost considering the

local providers’ poor clinical competence. In fact,

this type of situation is already very common in rural

China.3 16 25

Under such circumstances, our findings imply

that the difference in the utilisation of VCs might be

related to ethnic minority providers’ underdeveloped

clinical competence. Despite the small number of

previous studies, the current evidence is consistent

with the main findings.1 24 On the one hand, early

studies suggested that the quality of health providers limited the utilisation of primary healthcare.3 4 16 On

the other hand, ethnic minority providers usually

experience less supportive learning environments

during their medical studies, which might help

explain the lag in their clinical competence.33 34 35

Therefore, we believe that uniformly improving the

clinical competence of village providers, especially

that of ethnic minority village providers, is conducive

to improving the utilisation of primary healthcare.1 36

The Government of the People’s Republic of

China understands the benefits of improving the

clinical competence of village providers. A series of

human resource policies for health launched in 2010

had a positive impact in rural China.37 Among these

policies, the encouragement of external training

for healthcare providers has been proven effective

and necessary.36 38 39 In-service training for village

providers could help these providers be informed of

the latest knowledge and skills to manage diseases,

which could significantly improve the quality of their

medical services.36 The government has implemented

actions to encourage the training of ethnic minorities

since 2009.40 Thus, the appropriate introduction of

re-education and more medical training should be

adopted among ethnic minority providers.

Considering previous studies with analyses

based mainly on the utilisation of healthcare from

the patient perspective, our study might be the

first investigation to examine healthcare providers’

ethnicity and clinical competence.10 11 32 In addition,

our quantitative data include a rich set of detailed

information of VCs regarding out-patient visits

and providers’ clinical competence. We hope that

our findings offer key insights into the utilisation of

primary healthcare in rural China.

Our study has two main limitations. First, the

participants in this study were recruited from rural

Southwest China, so unavoidably, the nationwide

validity of our findings is limited. Second, the results

were limited by the cross-sectional nature of the

study, and no causal effect between the providers’

clinical competence and the utilisation of primary

healthcare was detected. Future research could

investigate how different ethnic providers influence

the utilisation of VCs and seek to adopt multiple

measures to reduce bias in investigations.

Conclusions

In conclusion, this study reveals differences in the utilisation of primary healthcare between ethnic

minority providers and Han Chinese providers at

VCs in rural areas in Southwest China. Notably, the

results indicate that higher clinical competence is

more likely to drive the utilisation of VCs. We believe

that the results of this study provide compelling

evidence that ethnic minority healthcare providers

in Southwest China require further enhancement

with respect to their clinical competence.

Author contributions

Concept or design: All authors.

Acquisition of data: All authors.

Analysis or interpretation of data: All authors.

Drafting of the manuscript: All authors.

Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: All authors.

Acquisition of data: All authors.

Analysis or interpretation of data: All authors.

Drafting of the manuscript: All authors.

Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: All authors.

All authors had full access to the data, contributed to the study, approved the final version for publication, and take responsibility for its accuracy and integrity.

Conflicts of interest

As an adviser of the journal, Y Shi was not involved in the peer review process. Other authors have disclosed no conflicts of interest.

Funding/support

H Yi received funding for this study from the Health and Hope

Fund of the Business Development Center of the Red Cross

Society of China and UCB of Belgium. Y Shi received funding

from 111 Project (Grant number B16031), and Q Gao received

funding from Innovation Capability Support Program of

Shaanxi (Grant number 2022KRM007). The funders had no

role in study design, data collection/analysis/interpretation,

or manuscript preparation.

Ethics approval

The study was approved by the Peking University Institutional

Review Board (Ref IRB 00001052-17033). The board approved

the verbal consent procedure. Informed consent from all

respondents as a requirement for completing the survey.

References

1. Li X, Lu J, Hu S, et al. The primary health-care system in

China. Lancet 2017;390:2584-94. Crossref

2. Liu Q, Wang B, Kong Y, Cheng KK. China’s primary healthcare

reform. Lancet 2011;377:2064-6. Crossref

3. Li YN, Nong D, Wei B, Feng QM, Luo HY. The impact of

predisposing, enabling, and need factors in utilization of

health services among rural residents in Guangxi, China.

BMC Health Serv Res 2016;16:592. Crossref

4. Sylvia S, Xue H, Zhou C, et al. Tuberculosis detection

and the challenges of integrated care in rural China: A

cross-sectional standardized patient study. PLoS Med

2017;14:e1002405. Crossref

5. Dong X, Liu L, Cao S, et al. Focus on vulnerable populations

and promoting equity in health service utilization—an

analysis of visitor characteristics and service utilization of

the Chinese community health service. BMC public health

2014;14:503. Crossref

6. Li Z. Healthcare reform and the development of China’s

rural healthcare: a decade’s experience [in Chinese].

Chinese Rural Economy 2019;9:1-22.

7. National Bureau of Statistics of China, PRC Government.

China Statistical Yearbook 2019. Available from: http://www.stats.gov.cn/tjsj/ndsj/2019/indexch.htm. Accessed 20

Oct 2020.

8. Sun J, Luo H. Evaluation on equality and efficiency of

health resources allocation and health services utilization

in China. Int J Equity Health 2017;16:127. Crossref

9. China Statisitcs Press. China Health Statistical Yearbook

2018. Available from: https://data.cnki.net/area/Yearbook/Single/N2019030282?z=D09. Accessed 9 May 2020.

10. Zhang X, Wu Q, Shao Y, Fu W, Liu G, Coyte PC. Socioeconomic inequities in health care utilization in

China. Asia Pac J Public Health 2015;27:429-38. Crossref

11. Wang M, Fang H, Bishwajit G, Xiang Y, Fu H, Feng Z.

Evaluation of rural primary health care in Western China:

a cross-sectional study. Int J Environ Res Public Health

2015;12:13843-60. Crossref

12. Shi Y, Xue H, Wang H, Sylvia S, Medina A, Rozelle S.

Measuring the quality of doctors’ health care in rural

China: an empirical research using standardized patients

[in Chinese]. Studies in Labor Econ 2016;4:48-71.

13. van Zanten M, Boulet JR, McKinley DW. The influence of

ethnicity on patient satisfaction in a standardized patient

assessment. Acad Med 2004;79(10 Suppl):S15-7. Crossref

14. LaVeist TA, Nuru-Jeter A, Jones KE. The association of

doctor-patient race concordance with health services

utilization. J Public Health Policy 2003;24:312-23. Crossref

15. Li Z, Li Y, Cui J. Development history of Chinese minority

traditional medicine [in Chinese]. Med Philosophy

(Humanistic & Soc Med Ed) 2011;32:78-81.

16. Wu D, Lam TP. Underuse of primary care in China: the scale, causes, and solutions. J Am Board Fam Med

2016;29:240-7. Crossref

17. Sandberg J. Understanding human competence at work: an interpretative approach. Acad Manage J 2000;43:9-25. Crossref

18. Liu W, Ding Y, Yang X. The determinants of rural labor migration in minority regions [in Chinese]. Population J 2015;37:102-12.

19. Shi L, Sai D. An empirical analysis of income inequality

between a minority and the majority in urban China: the

case of Ningxia Hui Autonomous Region. Rev Black Polit

Econ 2013;40:341-55. Crossref

20. Li L, Li XG. Ethnicity, social capital and income gap: a

comparative study of the Northwest ethnic group and

the Western Han nationality [in Chinese]. J Sun Yat-sen

University (Social Science Edition) 2016;56:161-71.

21. Gustafsson B, Sai D. Temporary and persistent poverty

among ethnic minorities and the majority in rural China.

Rev Income Wealth 2009;55:588-606. Crossref

22. China National Knowledge Infrastructure. BMJ;

Why are ethnic minority doctors less successful

than white doctors? Available from: https://schlr.cnki.net/en/Detail/index/SPQDLAST/SPQD48BA99708EE31C6710E1A02B2C34186A. Accessed 12 Jun 2020.

23. Li Y, Chi I, Zhang K, Guo P. Comparison of health services

use by Chinese urban and rural older adults in Yunnan

province. Geriatr Gerontol Int 2006;6:260-9. Crossref

24. Anand S, Fan VY, Zhang J, et al. China’s human resources

for health: quantity, quality, and distribution. Lancet

2008;372:1774-81. Crossref

25. Meng Q, Liu X, Shi J. Comparing the services and quality of

private and public clinics in rural China. Health Policy Plan

2000;15:349-56. Crossref

26. Zhang Q, Chen J, Yang M, et al. Current status and job

satisfaction of village doctors in western China. Medicine

(Baltimore) 2019;98:e16693. Crossref

27. Chinese Statistics Press. National Accounts. In: China

Statistical Yearbook 2017. Available from: http://www.stats.gov.cn/tjsj/ndsj/2017/indexeh.htm. Accessed 6 Jun 2020.

28. Wass V, Van der Vleuten C, Shatzer J, Jones R. Assessment of clinical competence. Lancet 2001;357:945-9. Crossref

29. Lever J, Krzywinski M, Altman N. Principal component analysis. Nat Methods. 2017;14:641-2. Crossref

30. Chinese Statistics Press. Population. In: China Statistical Yearbook 2017. Available from: http://www.stats.gov.cn/tjsj/ndsj/2017/indexch.htm. Accessed 14 Jun 2020.

31. Li X, Liu J, Huang J, Qian Y, Che L. An analysis of the

current educational status and future training needs of

China’s rural doctors in 2011. Postgrad Med J 2013;89:202-8. Crossref

32. Dias SF, Severo M, Barros H. Determinants of health care

utilization by immigrants in Portugal. BMC Health Serv

Res 2008;8:207. Crossref

33. Myers SL, Xiaoyan G, Cruz BC. Ethnic minorities, race, and

inequality in China: a new perspective on racial dynamics.

Rev Black Polit Econ 2013;40:231-44. Crossref

34. Esmail A, Everington S. Racial discrimination against

doctors from ethnic minorities. BMJ 1993;306:691-2. Crossref

35. Iacobucci G. Specialty training: ethnic minority doctors’ reduced chance of being appointed is “unacceptable”. BMJ 2020;368:m479. Crossref

36. Zhang M, Wang W, Millar R, Li G, Yan F. Coping and

compromise: a qualitative study of how primary health

care providers respond to health reform in China. Human

Resour Health 2017;15:50. Crossref

37. Tan X, Liu X, Shao H. Healthy China 2030: a vision for

health care. Value Health Reg Issues 2017;12:112-4. Crossref

38. Windish DM, Reed DA, Boonyasai RT, Chakraborti C,

Bass EB. Methodological rigor of quality improvement

curricula for physician trainees: a systematic review and

recommendations for change. Acad Med 2009;84:1677-92. Crossref

39. Yi H, Wu P, Zhang X, Teuwen DE, Sylvia S. Market

competition and demand for skills in a credence goods

market: evidence from face-to-face and web-based non-physician

clinician training in rural China. PLoS One

2020;15:e0233955. Crossref

40. People Television. Training of ethnic minority grassroots

doctors in the central and western regions launched

[in Chinese]. Available from: http://tv.people.com.cn/n/2012/0915/c14645-19017341.html. Accessed 16 Jul 2020.