Hong Kong Med J 2022 Apr;28(2):152–60 | Epub 25 Mar 2022

© Hong Kong Academy of Medicine. CC BY-NC-ND 4.0

ORIGINAL ARTICLE (HEALTHCARE IN MAINLAND CHINA)

Teacher-to-parent communication and vision

care–seeking behaviour among primary school

students

K Du, PhD Candidate1; J Huang, PhD Candidate2; H Guan, PhD1; J Zhao, PhD1; Y Zhang, PhD Candidate1; Y Shi, PhD1

1 Center for Experimental Economics in Education, Shaanxi Normal University, Xi’an, China

2 College of Economics and Management, China Agricultural University, Beijing, China

Corresponding author: Dr H Guan (guanhongyu2016@163.com)

Abstract

Introduction: To determine the associations

between teacher-to-parent communication and

vision care–seeking behaviour among students.

Methods: This cross-sectional study included

19 934 students from 252 primary schools in

two prefectures in western China. Information

regarding the sampled students was collected

through questionnaires and vision examinations.

Eligible students with uncorrected refractive error

were allocated to four groups according to whether

and how parents were informed about vision

problems in their children: uninformed, informed

by only teachers or only students, or informed by

both. The relationship between teacher-to-parent

communication and vision care–seeking behaviour

was analysed by multiple logistic regression.

Results: Among valid responses (n=2922) analysed,

42.3% (n=1235) of parents were not informed about

vision problems in their children. Teacher-to-parent

communication enabled 35.9% (n=1050) of parents

to learn about vision problems in their children.

When only teachers informed parents, the odds of

students having refraction examinations (odds ratio

[OR]=1.499; P=0.002) and spectacles ownership

(OR=1.755; P=0.002) were significantly higher than

for students in the uninformed group. When both students and teachers informed parents, the odds of

students having refraction examinations (OR=5.565;

P<0.001) and spectacles ownership (OR=7.935;

P<0.001) were highest.

Conclusions: Knowledge of vision problems is an

essential step in vision care for students. Teacherto-

parent communication concerning vision

problems is positively associated with the rate of

vision care–seeking behaviour. Teacher-to-parent

communication provides an important route for

parents to learn about vision problems in their

children.

New knowledge added by this study

- Knowledge of vision problems is an essential step in vision care for students. More than 40% of parents were not informed by students or teachers about vision problems in their children.

- Teacher-to-parent communication is significantly associated with students having refraction examination and spectacles ownership.

- Teacher-to-parent communication provides an important method for parents to learn about vision problems in their children; it also reinforces the effects of students informing their parents.

- Policymakers should carefully consider the role of teachers in vision care for students; teacher-to-parent communication is a cost-effective way to enhance vision care–seeking behaviour among students.

- Teachers should participate in vision care for students, at least in the form of communication with parents.

Introduction

Uncorrected refractive error is the leading cause

of visual impairment among children worldwide; it

affects nearly 13 million children under the age of

16 years, half of whom live in China.1 Uncorrected

refractive error can lead to various broader issues if not treated in a timely manner.2 Uncorrected

refractive error in school-aged children reportedly

has negative effects on academic performance,3

physical and mental health, and quality of life.4

Fortunately, over 80% of refractive error can be

easily and safely corrected by accurately prescribed spectacles.5 However, the correction rate in rural

areas in China is very low.6 A study in 2014 revealed

that in rural China, as few as one in six children

needing spectacles actually wears them.7

The lack of vision problem awareness at the

family level is an important contributing factor in

the low rate of refractive correction in rural areas.8

There are two main ways for parents to learn about

vision problems in their children: from the children

themselves and from their teachers. Information

conveyed by a teacher is more likely to receive

parental attention and cause parents to take action.9

Teacher-to-parent communication (TPC) allows

parents and teachers to exchange information,

strengthen feelings of mutual obligation and trust,

and coordinate efforts to help students thrive in

terms of mental health, school engagement, and

school performance.10 11

However, the relationship between TPC and

vision care–seeking behaviour among students

is not well-investigated, particularly in more

realistic settings. Researchers have indicated that

teachers have an important role in vision care

for students. Chinese rural teachers can perform

vision screening accurately for students with only

moderate training.12 Teachers can help to improve

the uptake of spectacles and the use of spectacles

among students who participate in free spectacles

distribution programmes.13 Considering the

potentially important role of teachers in vision care

for students, further analyses are needed regarding

the interactions between TPC and vision care–seeking behaviour among students.

In this study, our overall goal was to identify

the associations between TPC and vision care–seeking behaviour among students. Specifically,

when teachers informed students’ parents that their

children could not see the blackboard clearly, we

assessed whether the information sharing interacted

with vision care–seeking behaviour among students,

including refraction examinations and spectacles

ownership. To meet this goal, we had three specific

objectives. First, we documented the rates of

vision care–seeking behaviour in four groups,

according to whether and how the parents were

informed about vision problems in their children.

Second, we explored the relationship between

TPC and refraction examination history. Third, we

investigated the association between spectacles

ownership and TPC.

Methods

Setting

The data analysed in this study were collected in two adjacent provinces (Gansu and Shaanxi) of western

China in September 2012. In each of the provinces,

one prefecture that is of the province was chosen for

this study: Tianshui prefecture in Gansu and Yulin

prefecture in Shaanxi. For sample selection, we

obtained a list of all rural primary schools in each

prefecture. We randomly selected 252 townships,

then randomly selected one school per township

for inclusion in the study. Within each school, one

class was randomly chosen in each of the fourth and

fifth grades. This cross-sectional study was approved

by Stanford University (No. ISRCTN03252665,

registration site: http://isrctn.org).

Data collection

The data collected in this study included three parts:

a standardised maths test, questionnaires, and

a vision screening. The standardised maths test

was timed (25 min) and proctored by two study

enumerators at each school. Mathematics testing

was conducted to reduce the effect of home learning

on performance; this facilitated greater focus on

classroom learning.7 We standardised the baseline

maths score, such that the mean score was 0 and the

standard deviation was 1.

Questionnaires were used to collect data from

students, including grade, gender, boarding status,

the main caregivers, parental education, and siblings.

A parental questionnaire asked whether any family

members wore spectacles and whether the parents

thought spectacles were useful. Family wealth was

calculated by summing the values, as reported in

the China Rural Household Survey Yearbook,14 of

the items on the list of 13 durable consumer goods

owned by the family. A parental questionnaire asked

about ownership of 13 selected items as an index of family wealth. The distance from the school to the

county seat was approximated using Google Maps

(Google LLC, Mountain View [CA], United States).

Vision care–seeking behaviour was measured

via self-reporting on the questionnaires administered

to students; it included refraction examination

history (defined as undergoing a refraction

examination in a professional institution before the

day of questionnaire administration) and spectacle

ownership (defined as the possession of spectacles

before the day of questionnaire administration). To

reduce the measurement error, we also asked these

two questions to each student’s parents. Individuals

with inconsistent answers were excluded from the

study.

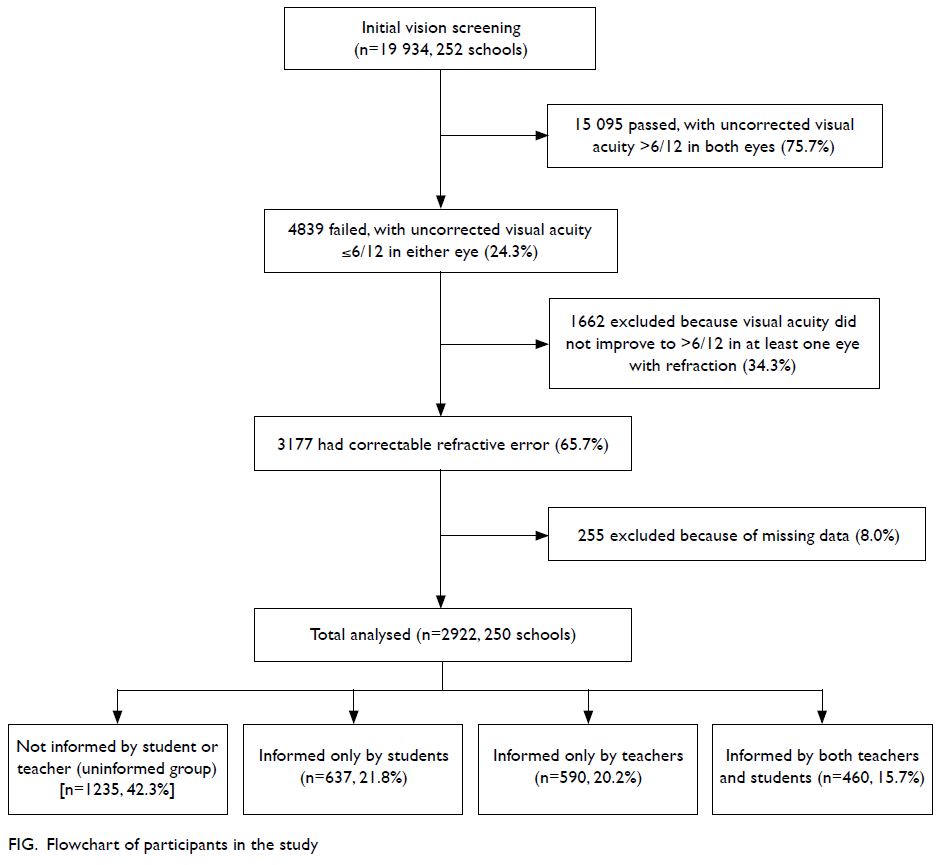

Teacher-to-parent communication was

measured by asking parents whether they had been

informed by teachers that their children could not

see the blackboard clearly. Students were also asked

whether they had informed their parents about their

vision problems. Based on the responses to these two questions, we allocated all students with vision

problems into four groups: neither teachers nor

students informed parents (uninformed group), only

students informed parents, only teachers informed

parents, and both teachers and students informed

parents (Fig).

Visual acuity assessment and refraction

After completion of the maths test and

questionnaires, a two-part eye examination was

administered to students by a team of qualified

optometrists who followed a prescribed protocol to

ensure standardisation and quality.

First, visual acuity screenings were administered

using Early Treatment Diabetic Retinopathy Study

eye charts, which are regarded as the worldwide

standard for accurate visual acuity measurement.15

Visual acuity values, measured by the Early

Treatment Diabetic Retinopathy Study eye charts,

were transformed into logarithm of the minimum

angle of resolution (logMAR) units; logMAR is one of the most commonly used continuous scales in the

field of ophthalmology/optometry.3 15 Students who

failed the visual acuity screening test (using a visual

acuity cut-off of ≤6/12 in either eye) were enrolled in

a second vision test.

The second vision test was conducted by a

team of one optometrist, one nurse, and one staff

assistant. Children with uncorrected visual acuity

≤6/12 in either eye underwent cycloplegia with up to

3 drops each of cyclopentolate 1% and proparacaine

hydrochloride 0.5%. To ensure that vision problems

among the students could be treated using spectacles,

the students were examined via automated refraction

(Topcon KR 8900; Topcon, Tokyo, Japan) and

subjective refinement by a local optometrist who had

previously been trained by experienced optometrists

from Zhongshan Ophthalmic Center.

Vision problems in the students could be

corrected using spectacles if they met the following

criteria: first, an uncorrected (ie, without spectacles)

visual acuity of ≤6/12 in either eye and refractive

error within the limits associated with significantly

greater improvement in visual acuity upon correction

(myopia ≤-0.75 dioptres, hyperopia >=2.00 dioptres,

or astigmatism [non-spherical refractive error]

>=1.00 dioptres)7; second, visual acuity improvement

to >6/12 in both eyes was possible with spectacles.

Statistical methods

Descriptive statistical analyses were performed

to summarise the demographics of the students

and to compare the proportions of students who

had undergone refraction examination and owned

spectacles among four groups by using the Chi

squared test and one-way analysis of variance.

Refraction examination and spectacle ownership

were both regarded as dummy variables that equalled

one if the corresponding behaviour had occurred

before the study.

Multiple logistic regression was conducted

to ascertain the relationship between TPC and

vision care–seeking behaviour, including refraction

examination history and spectacle ownership. In

all regression analyses, the same covariates were

controlled. Variables included standardised maths

score, grade (grade 5=1), sex (male=1), boarding

status (boarding at school=1), logMAR (continuous

scale of visual acuity), whether parents are the

main caregivers (yes=1), parental education for

both mother and father (completed >=12 years of

education=1), siblings (at least one sibling=1),

whether any family members wear spectacles

(yes=1), whether parents think spectacles are useful

(yes=1), family wealth, and distance from school to

the county seat. A P value of <0.05 was regarded as

a statistically significant difference. All analyses were

performed using Stata 14.1 (Stata Corp, College

Station [TX], United States).

Results

Among 19 934 students in 252 schools, 4839 (24.3%)

students failed the vision screening. In total, 3177

(65.7%) students in 250 schools were eligible for

spectacles to improve visual acuity (two schools

were excluded because no students at either school

met the inclusion criteria). After the exclusion of

students with missing information, the remaining

2922 students were divided into four subgroups.

In our study, 42.3% (n=1235) of parents were not

informed by either their children or their children’s

teachers. Teacher-to-parent communication

enabled 35.9% (n=1050) of parents to learn about

vision problems in their children. In total, 20.2%

(n=590) parents were informed only by teachers and

15.7% (n=460) were informed by both teachers and

students, respectively (Fig).

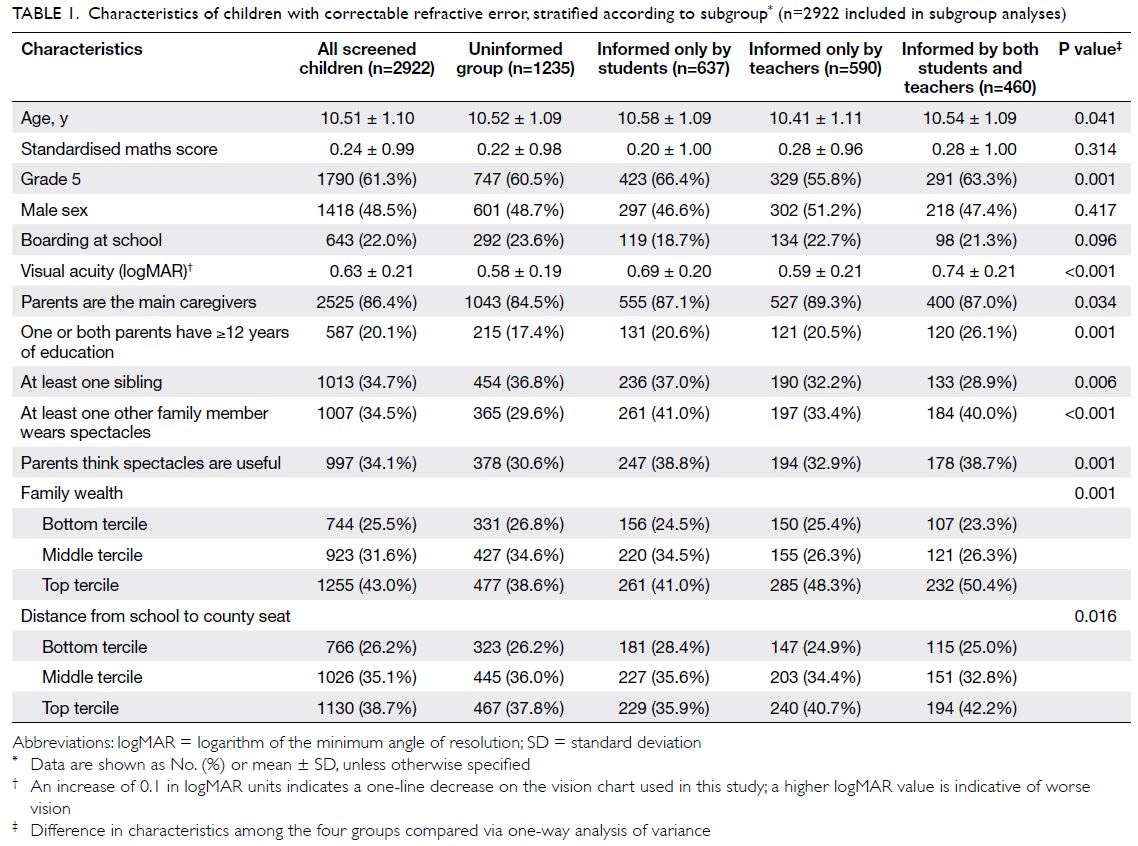

The mean (± standard deviation) age of all

students with vision problems was 10.51 ± 1.10 years

(range, 8-15). Among all respondents, 1418 (48.5%)

were boys and 1504 (51.5%) were girls. Most students’

main caregivers were their parents (86.4%). Other

participants’ characteristics are shown in Table 1,

including the comparison of characteristics among

the four groups.

Table 1. Characteristics of children with correctable refractive error, stratified according to subgroup* (n=2922 included in subgroup analyses)

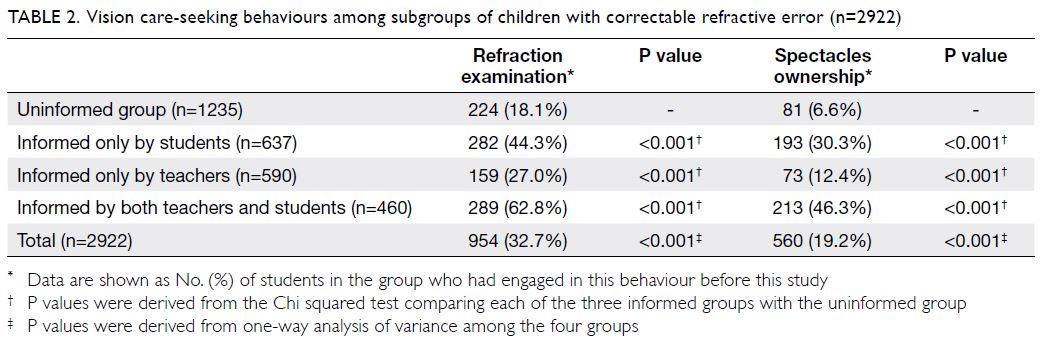

The rate of vision care–seeking behaviour

among all students was very low. The number of

students who received vision care services decreased

gradually at each step. In all, 57.7% (n=1687) of

parents were informed about vision problems in

their children; only 32.7% (n=954) of all parents took

their children for refraction examinations. Finally,

only 19.2% (n=560) of students owned spectacles

before the study (Table 2). The rates of vision care–seeking behaviour significantly differed among the

four groups. When comparing the rates of refraction

examination history and spectacle ownership among

three types of informed groups with the uninformed

group, we found significant differences (P<0.001) in

all comparisons (Table 2). In the uninformed group,

comparatively few parents took their children to

receive a refraction examination and/or obtained

spectacles for their children. In the group where

parents were informed only by students, more

children had undergone refraction examinations

and/or owned spectacles than in the group where

parents were informed only by teachers. When both

teachers and students informed parents, the rates of

refraction examinations and spectacles ownership

were highest among the four groups.

Table 2. Vision care-seeking behaviours among subgroups of children with correctable refractive error (n=2922)

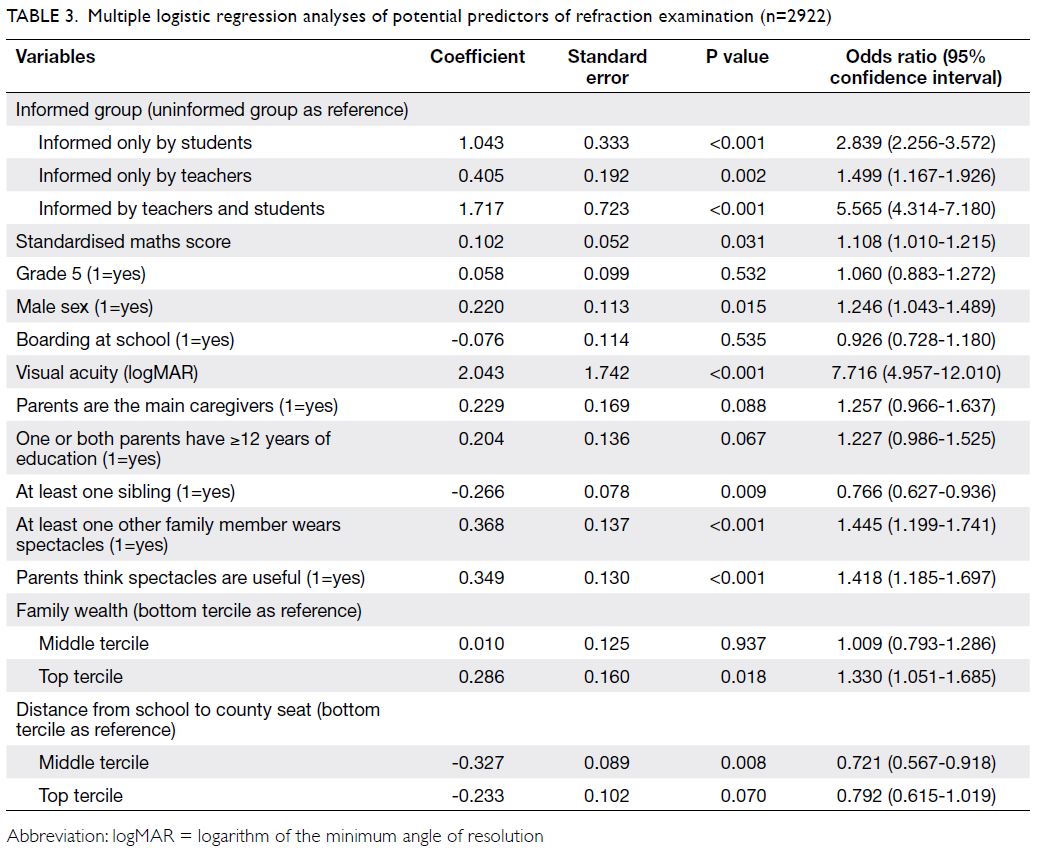

In the multiple logistic regression analyses of

potential predictors of refraction examination, we

found that information sharing (including TPC) was

significantly associated with refraction examination

history (Table 3). Compared with the uninformed

group, the odds of students having a refraction

examination was higher in each of the other three

groups. When only teachers informed parents, the odds ratio (OR) was 1.499, which was lower than

in the group where only students informed parents

(OR=2.839). When both students and teachers

informed parents, the odds of students having a

refraction examination was highest (OR=5.565). Additionally, the following characteristics were significantly positively

associated with refraction examination history:

receiving a better maths score (P=0.031), being male

(P=0.015), having a worse visual ability (P<0.001),

having at least one other family member who wears

spectacles (P<0.001), being in the top wealth

tercile (P<0.018), and having parents who think that spectacles are useful (P<0.001) [Table 3].

Table 3. Multiple logistic regression analyses of potential predictors of refraction examination (n=2922)

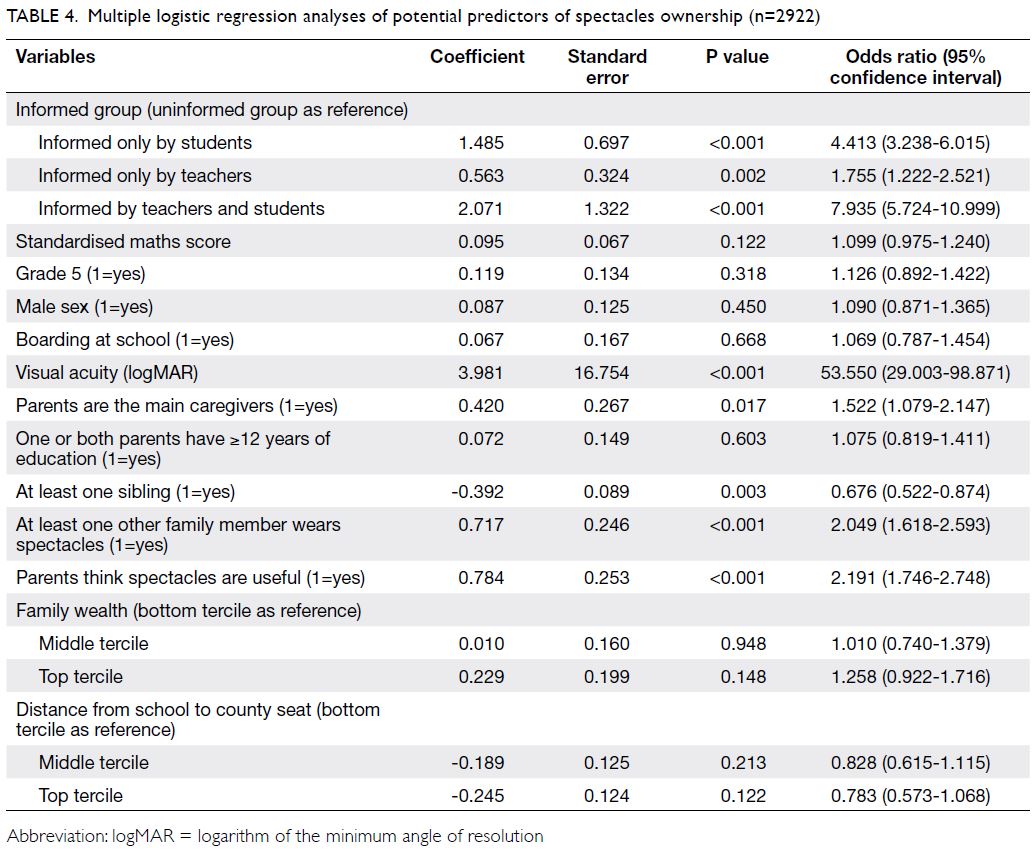

Multiple logistic regression analyses were

used to estimate the relationship between TPC

and spectacles ownership (Table 4). Teacher-to-parent

communication was significantly positively

associated with spectacles ownership, regardless of

whether students informed parents about their vision

problems. The odds of students having spectacles

ownership in the group where parents were informed

by both teachers and students (OR=7.935) was

almost 1.8 times that in the group where parents were

informed only by students (OR=4.413). The odds of

students having spectacles ownership in the group

where parents were informed by students only was

twice that in the group where parents were informed

only by teachers (OR=1.755). Furthermore, the

following characteristics were significantly positively

associated with spectacles ownership: having worse

visual acuity (P<0.001), having parents as the main

caregivers (P<0.017), having at least one other family

member who wears spectacles (P<0.001), and having

parents who think spectacles are useful (P<0.001).

Notably, students with at least one sibling (P=0.003)

were more unlikely to purchase spectacles (Table 4).

Table 4. Multiple logistic regression analyses of potential predictors of spectacles ownership (n=2922)

Discussion

Factors affecting vision care–seeking

behaviour

In this study, we found that the rate of vision care–seeking behaviour was very low in our sample area,

similar to previous results.16 17 There are two possible

reasons for the low vision care–seeking behaviour

rate. First, parents may not know that their children

cannot see the blackboard clearly; thus, they will

not actively seek vision care services. Second, the

number of students receiving vision care services

has been decreasing throughout the process of three

stages: parental knowledge that their children have

vision problems, parental action to ensure their

children undergo refraction examinations, and

parental acquisition of spectacles for their children.

Furthermore, despite sufficient information, many

parents do not seek vision care services because of

misinformation or misunderstanding.18 19

Knowledge of vision problems is the initial

aspect of the vision care–seeking process for

students. The rates of refraction examination history

(18.1%) and spectacles ownership (6.6%) were the lowest in the uninformed group, which comprised

more than 40% of parents in this study. When

parents were informed by students and/or teachers,

the rate of vision care–seeking behaviour was much

higher. Teacher-to-parent communication provides

an important method for parents to learn about

vision problems in their children. In this study,

20.2% of parents learned about their children’s vision

problems only from teachers.

Effects of teacher-to-parent communication

on vision care–seeking behaviour

Although a considerable proportion of students did

not receive vision care in the care-seeking process,

TPC can reduce this to some extent. When both

teachers and students informed parents, the rate

of spectacles ownership was the highest. In the group that parents were

informed by both teachers and students, 46% of

students finally received spectacles, which is 7-times

more students than in the group in which parents

were not informed. Furthermore, the odds of students

having refraction examination and spectacles

ownership were higher in the group where parents

were informed only by students than in the group where parents were informed only by teachers. These

additional opportunities may increase the likelihood

that parents act to correct those vision problems.

There are two possible explanations for the

positive association between TPC and vision care–seeking behaviours among students in this study.

Teacher-to-parent communication provides an

important channel for parents to learn about the

vision problems in their children, which is a starting

point and key aspect of vision care for students.

Second, TPC reinforces the effects of students

informing their parents. Compared with the group

where parents were informed only by students,

the rates of refraction examinations and spectacles

ownership were nearly twofold greater in the group

where parents were informed by both students and

teachers. This was presumably because parents

learned about vision problems in their children from

two sources; the information from the students was

reinforced by the information from the teacher.20

Implications of promoting teacher-to-parent

communication

Small efforts by teachers may have great benefits in terms of vision care for students. Compared with intervention programmes to increase the

correction rate,7 21 the results of present study

indicate that TPC is both easy and cost-effective.

Teachers should inform parents that their children

cannot see the blackboard clearly. Studies of free

spectacles distribution programmes have also shown

that teachers can improve spectacles usage rates

among students who have received spectacles.13 22

Moreover, wearing spectacles can improve academic

performance,7 21 implying that TPC may both

increase the correction rate and have a positive role

in academic performance. Therefore, policymakers

should carefully consider the role of teachers in

protecting vision among students. Indeed, the

Chinese Government has noted that multilateral

cooperation (involving teachers, schools, parents,

and society in general) should be encouraged to

protect vision among students, in an effort to improve

health status among young people by 2020.23

Unfortunately, the TPC ratio is very low. A

recent study in China noted that approximately half

of the parents and teachers communicate, in any

form, during the course of an entire school year.24

In our study, the proportion of parents who were

informed by teachers was only approximately 36%,

including parents informed only by teachers (20%)

and parents informed by both teachers and students

(16%). This is presumably because teachers do not

know a particular student’s vision status because it

is not a vital consideration for most education work.

Vision screening is the best method to detect vision

problems.25 The education bureau and the health

bureau should conduct routine vision screenings

and encourage teachers to engage in vision

protection (eg, communicate with parents about

vision problems in students).5 25 If those stakeholders

began to take action, more parents will learn about

vision problems in their children and seek vision

care services.

Effects of students’ informing on vision care–seeking behaviour

In the present study, the effects of students

informing parents were greater than the effects of

teachers informing parents when only one party

informs the parents of vision problems. This finding

implies that parents were more likely to act when

they received information from students. However,

students are often unaware of vision problems. Thus,

teachers have an important effect; a previous survey

reported that teachers were most likely to perceive

visual impairment in children (70.6%), followed by

the children’s parents (18.9%) and by the children

themselves (7.9%).26 Therefore, careful attention is

needed concerning the role of teachers in identifying

vision problems, encouraging communication

between students and their parents about such

problems.

Limitations

There were three important limitations in this

study. First, the study could not investigate any

causal link between TPC and vision care–seeking

behaviour because of the cross-sectional design.

However, the findings provide a foundation for

follow-up analyses of causality. Second, this study

only focused on whether teachers informed parents

about vision problems in their children; it did not

collect information concerning how parents were

informed. Teacher-to-parent communication may

happen in many ways, particularly in the internet

era (eg, teachers communicate with parents via

instant messenger). Additional research is needed to

determine the types of TPC that are most effective

in vision care for students. Third, the participants

in this study were recruited from two provinces in

rural north-western China, which limits the external

validity of the findings. Despite this limitation,

in the context of widespread uncorrected vision

impairment among students,27 our study still has

important implications for improving the uptake

rate of vision care services.

Conclusions

Teacher-to-parent communication can significantly

enhance the rates of refractive examinations and

spectacles uptake through direct and indirect ways.

Not only teacher informing provides a new channel

for parents to learn about their students’ vision

problems, but also reinforce the information told

by students. Teacher-to-parent communication is

an easy and cost-effective way to improve the rate

of vision care–seeking behaviour. Policymakers

should encourage teachers to be more involved

in students’ vision protection, such as motivating

teachers to communicate timely with parents about

the students’ vision status.

Author contributions

Concept or design: K Du, J Huang.

Acquisition of data: H Guan, Y Shi.

Analysis or interpretation of data: All authors.

Drafting of the manuscript: K Du.

Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: All authors.

Acquisition of data: H Guan, Y Shi.

Analysis or interpretation of data: All authors.

Drafting of the manuscript: K Du.

Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: All authors.

All authors had full access to the data, contributed to the study, approved the final version for publication, and take responsibility for its accuracy and integrity.

Conflicts of interest

All authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Funding/support

This research was supported by the 111 Project (Ref: B16031).

H Guan has received funding from the National Natural

Science Foundation of China (Ref: 71803107). The funders

had no role in the design of the study, the acquisition or

interpretation of results, or the decision to submit the

manuscript for publication.

Ethics approval

This study was approved by Stanford University (No.

ISRCTN03252665). Permission was received from local

boards of education in each region and the principals of all

schools. The presented data are anonymised, and the risk

of identification is low. The principles of the Declaration of

Helsinki were followed throughout.

References

1. Jonas JB, Xu L, Wei WB, et al. Myopia in China: a population-based cross-sectional, histological, and

experimental study. The Lancet 2016;388:S20. Crossref

2. Smith TS, Frick KD, Holden BA, Fricke TR, Naidoo KS. Potential lost productivity resulting from the global burden

of uncorrected refractive error. Bull World Health Organ

2009;87:431-7. Crossref

3. Yi H, Zhang L, Ma X, et al. Poor vision among China’s rural primary school students: Prevalence, correlates and consequences. China Econ Rev 2015;33:247-62. Crossref

4. Chadha RK, Subramanian A. The effect of visual impairment on quality of life of children aged 3-16 years.

Br J Ophthalmol 2011;95:642-5. Crossref

5. World Health Organization. Sight test and glasses could dramatically improve the lives of 150 million people with

poor vision. 2006; Available from: http://www.who.int/mediacentre/news/releases/2006/pr55/en/. Accessed 9 Jan

2018.

6. He M, Xu J, Yin Q, Ellwein LB. Need and challenges of refractive correction in urban Chinese school children.

Optom Vis Sci 2005;82:229-34. Crossref

7. Ma X, Zhou Z, Yi H, et al. Effect of providing free glasses on children’s educational outcomes in China: cluster randomized controlled trial. BMJ 2014;349:g5740. Crossref

8. Resnikoff S, Pasolini D, Mariotti SP, Pokharel GP. Global magnitude of visual impairment caused by uncorrected

refractive errors in 2004. Bull World Health Organ 2008;86:63-70. Crossref

9. Adams KS, Christenson SL. Trust and the family–school relationship examination of parent–teacher differences

in elementary and secondary grades. J Sch Psychol

2000;38:477-97. Crossref

10. Franklin CG, Kim JS, Ryan TN, Kelly MS, Montgomery KL. Teacher involvement in school mental health interventions: A systematic review. Child Youth Serv Rev 2012;34:973-82. Crossref

11. Kraft M, Dougherty SM. The effect of teacher-family communication on student engagement: evidence from a

randomized field experiment. J Res Educ Eff 2013;6:199-222. Crossref

12. Sharma A, Li L, Song Y, et al. Strategies to improve the accuracy of vision measurement by teachers in rural Chinese secondary schoolchildren: Xichang pediatric

refractive error study (X-PRES) report no. 6. Arch

Ophthalmol 2008;126:1434-40. Crossref

13. Yi H, Zhang H, Ma X, et al. Impact of free glasses and a teacher incentive on children’s use of eyeglasses: a cluster-randomized controlled trial. Am J Ophthalmol

2015;160:889-96.e1. Crossref

14. China National Bureau of Statistics. China Statistical Yearbook. Beijing, China: China State Statistical Press;

2013.

15. Camparini M, Cassinari P, Ferrigno L, Macaluso C. ETDRS-Fast: implementing psychophysical adaptive

methods to standardized visual acuity measurement with

ETDRS charts. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 2001;42:1226-31.

16. Qian DJ, Zhong H, Nie Q, Li J, Yuan Y, Pan CW. Spectacles need and ownership among multiethnic students in rural

China. Public Health 2018;157:86-93. Crossref

17. Zhao J, Guan H, Du K, et al. Visual impairment and spectacles ownership among upper secondary school

students in northwestern China. Hong Kong Med J

2020;26:35-43. Crossref

18. Dudovitz RN, Izadpanah N, Chung PJ, Slusser W. Parent, teacher, and student perspectives on how corrective lenses improve child wellbeing and school function. Matern Child

Health J 2016;20:974-83. Crossref

19. Senthilkumar D, Balasubramaniam SM, Kumaran SE, Ramani KK. Parents’ awareness and perception of children’s eye diseases in Chennai, India. Optom Vis Sci

2013;90:1462-6. Crossref

20. Verhulst FC, Dekker MC, van der Ende J. Parent, teacher and self-reports as predictors of signs of disturbance in

adolescents: whose information carries the most weight?

Acta Psychiatr Scand 1997;96:75-81. Crossref

21. Ma Y, Congdon N, Shi Y, et al. Effect of a local vision care center on eyeglasses use and school performance in

rural China: a cluster randomized clinical trial. JAMA

Ophthalmol 2018;136:731-7. Crossref

22. Wang X, Ma Y, Hu M, et al. Teachers’ influence on purchase

and wear of children’s glasses in rural China: The PRICE

study. Clin Exp Ophthalmol 2019;47:179-86. Crossref

23. Ministry of Education, PRC Government. Ministry

of education on implement plan for comprehensive

prevention and control of myopia among children and

adolescents. Available from: http://www.moe.gov.cn/srcsite/A17/moe_943/s3285/201808/t20180830_346672.html. Accessed 9 Jan 2020.

24. Li G, Lin M, Liu C, Johnson A, Li Y, Loyalka P. The prevalence of parent-teacher interaction in developing

countries and its effect on student outcomes. Teach Teach

Educ 2019;86:102878. Crossref

25. Glewwe P, Park A, Meng Z. A better vision for development: eyeglasses and academic performance in rural primary

schools in China. J Dev Econ 2016;122:170-82. Crossref

26. Alves MR, Temporini ER, Kara-José N. Ophthalmological

evaluation of schoolchildren of the public educational

system of the city of São Paulo, Brazil: medical and social

aspects [in Portuguese]. Arq Bras Oftalmol 2000;63:359-63. Crossref

27. Ma Y, Zhang X, He F, et al. Visual impairment in rural and migrant Chinese school-going children: prevalence,

severity, correction and associations. Br J Ophthal

2022;106:275-80. Crossref