Hong Kong Med J 2021 Apr;27(2):148–9 | Epub 7 Apr 2021

© Hong Kong Academy of Medicine. CC BY-NC-ND 4.0

COMMENTARY

Formulation of a departmental COVID-19

contingency plan for contact tracing and facilities management

ST Mak, FRCSEd (Ophth), FHKAM (Ophthalmology)1,2,3; Kitty SC Fung, FHKAM (Pathology)4; Kenneth KW Li, FRCOphth, FHKAM (Ophthalmology)1,2

1 Department of Ophthalmology, United Christian Hospital, Hong Kong

2 Department of Ophthalmology, Tseung Kwan O Hospital, Hong Kong

3 Quality and Safety Office, Kowloon East Cluster, Hospital Authority, Hong Kong

4 Department of Pathology, United Christian Hospital, Kwun Tong, Hong Kong

Corresponding author: Dr ST Mak (dr.makst@gmail.com)

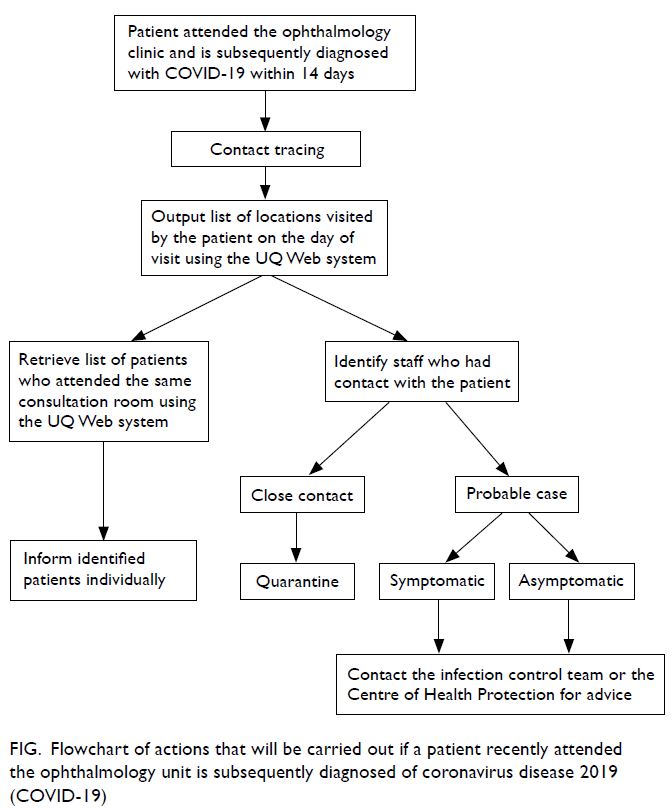

In February 2020, the ophthalmology unit of Kowloon

East Cluster, in collaboration with the infection

control team, formulated this contingency plan with

a main aim of facilitating the contact tracing of staff

and patients to control the spread of coronavirus

disease 2019 (COVID-19).1 The plan also provided

guidance to our staff on facilities management.

Contact tracing

We followed the definition of contacts described

by the Chief Infection Control Officer Office of the

Hospital Authority of Hong Kong. Contact tracing

was conducted for all staff identified as a ‘close

contact’ or a ‘probable case’. ‘Close contacts’ were

defined as healthcare workers who had cared for

patient with confirmed COVID-19 (ie, within 14 days

[the incubation period of COVID-192] of symptom

onset or the date of diagnosis for asymptomatic

patients) without wearing appropriate personal

protective equipment (PPE). Appropriate PPE was

considered as surgical masks for routine patient

handling in the ophthalmology setting, or full

PPE including N95 respirators and face shields for

aerosol-generating procedures, such those involving

the use of transnasal drills or cautery.3 Staff who

developed fever or respiratory symptoms after

exposure to a patient with COVID-19 were managed

as ‘probable cases’. In case of doubt, the exposure

situation was discussed with the Chief Infection Control Officer Office of the Hospital Authority or the Centre of Health Protection.

In United Christian Hospital, Hong Kong,

allocation of patients to consultation rooms is

managed using proprietary in-house computer

software called ‘UQ Web’. The system allows

tracking of patient movement among the different

consultation rooms, facilitating tracing of doctors,

nursing staff, and allied health workers who had come

into contact with patients later confirmed to have

COVID-19. The system can also generate a list of

patients who attended the same consultation room, allowing for contact tracing. Identified patients are

informed individually and advised to report any

relevant symptoms. In-patients are monitored by

the hospital infection control team and out-patients

are monitored by the Centre for Health Protection.

The risk assessment depends on the duration, proper

wearing of a surgical mask, and the closeness of

contact with the patient with confirmed COVID-19

during the exposure. (Fig)

Figure. Flowchart of actions that will be carried out if a patient recently attended the ophthalmology unit is subsequently diagnosed of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19)

In addition, the contingency plan considers

facilities management. Patients with confirmed

COVID-19 requiring urgent ophthalmology

attendance are arranged as the final scheduled

appointment of the day, to minimise service

disruption, if possible. The patients are examined in

a designated room with a high-efficiency particulate

air filtration system capable of capturing sub-micron

particulate as small as 0.1 μm.4 All staff assessing

the patients wear appropriate PPE. The consultation

room and all instruments are disinfected with 1:49

diluted bleach or 70% alcohol, respectively. The room

is vacated for 48 hours, taking reference from the

hospital’s practice of operating theatre air sampling.

With six air changes per hour in general hospital

setting, a minimum of 69 minutes is adequate to

remove 99.9% of airborne contaminants. The plan

also includes contingency for backup rooms. For

example, our clinic has two investigation rooms for

checking visual acuity and intraocular pressure. All

tests were conducted in one room, and if it had to

be closed for terminal disinfection, the other room

could be used.

Split teams

The majority of healthcare activities require direct

patient contact, and most staff cannot work from

home. In anticipation of the need for quarantine or

isolation of our staff, our department implemented

a split team arrangement to ensure adequate

manpower at all times. In this arrangement, staff were allocated to teams that worked on alternate

work sites or work schedules. The teams were

physically segregated to minimise exposure and

cross-contamination, reducing potential disruption

to patient care. Because our team serves two hospitals

(United Christian Hospital and Tseung Kwan O

Hospital), our doctors routinely visit both hospitals,

sometimes on the same day. Administrative staff also

provide clerical support to the eye clinics of both

hospitals. To achieve split teams, our administrative

staff were split into two teams with each working in

one hospital only. During the peak of the COVID-19

outbreak in February 2020, administrative staff

worked from home. We also considered splitting

our doctors to work at one hospital only without

the need to provide service at both hospitals. This

split team arrangement for doctors and allied health

staff was successfully implemented in August and

September 2020, and December 2020 to February 2021.

Conclusion

We have regularly updated the contingency plan to reflect the latest available scientific evidence on

COVID-19. This system has been used for tracing

patients 3 times, with approximately 40 patients

successfully traced each time. We encourage fellow

departments and clinics to develop their own

contingency plans to prepare for the next wave of

COVID-19 or other future outbreaks or epidemics.

Author contributions

Concept or design: All authors.

Acquisition of data: ST Mak, KKW Li.

Analysis or interpretation of data: ST Mak, KKW Li.

Drafting of the manuscript: ST Mak, KKW Li.

Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: All authors.

Acquisition of data: ST Mak, KKW Li.

Analysis or interpretation of data: ST Mak, KKW Li.

Drafting of the manuscript: ST Mak, KKW Li.

Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: All authors.

All authors had full access to the data, contributed to the study, approved the final version for publication, and take responsibility for its accuracy and integrity.

Conflicts of interest

As an editor of the journal, KKW Li was not involved in the

peer review process. The other authors have no conflicts of

interest to disclose.

Funding/support

This commentary received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

References

1. Hellewell J, Abbott S, Gimma A, et al. Feasibility of

controlling COVID-19 outbreaks by isolation of cases and

contacts. Lancet Glo Health 2020;8:e488-96. Crossref

2. Linton NM, Kobayashi T, Yang Y, et al. Incubation period

and other epidemiological characteristics of 2019 novel

coronavirus infections with right truncation: a statistical

analysis of publicly available case data. J Clin Med 2020

17;9:538. Crossref

3. Workman AD, Jafari A, Welling DB, et al. Airborne aerosol

generation during endonasal procedures in the Era of

COVID-19: risks and recommendations. Otolaryngol

Head Neck Surg 2020 May 26. Epub ahead of print. Crossref

4. Perry JL, Agui JH, Vigayakumar R. Submicron and

nanoparticulate matter removal by HEPA-rated media

filters and packed beds of granular materials. NASA

technical report 2016: NASA/TM-2016-218224,

M-1414. Available from: https://ntrs.nasa.gov/search.

jsp?R=20170005166. Accessed 2 Jul 2020.