Hong

Kong Med J 2020 Dec;26(6):510–9 | Epub 16 Dec 2020

© Hong Kong Academy of Medicine. CC BY-NC-ND 4.0

REVIEW ARTICLE

Medication-related problems in older people:

how to optimise medication management

CW Wong, FHKAM (Medicine), FHKCP

Department of Medicine and Geriatrics, Caritas Medical Centre, Kowloon, Hong Kong

Corresponding author: Dr CW Wong (wong.chitwai@gmail.com)

Abstract

Older patients are at risk of medication-related

problems because of age-related physiological

changes and multiple medications taken for multiple

co-morbidities. The resultant polypharmacy is

frequently associated with inappropriate medication

use, which in turn contributes to a range of adverse

consequences, including geriatric syndromes (eg,

falls, cognitive decline, urinary incontinence)

and hospitalisation. In addition, medication non-adherence

or discrepancies between the medications

prescribed and those actually taken by patients,

either intentional or unintentional, are prevalent and

can lead to treatment failure. A large proportion of

adverse drug events are preventable, and medication

errors occur most commonly at the stages of

prescribing and subsequent monitoring. There are

a number of strategies to address these issues with

the aim of ensuring safe prescribing. Furthermore, deprescribing with withdrawal of medications that

are inappropriate or of minimal value for patients is

increasingly emphasised for optimising medication

management. In general, optimisation of medication

management should be patient-centred, considering

individual circumstances and preferences to

determine the treatment goals or priorities for

individual patients, and a multidisciplinary approach

is recommended.

Introduction

With advances in medicine, new drugs are developed

and approved every year for particular diseases and

conditions. In addition, evidence-based clinical

practice guidelines are being developed to assist

clinicians’ decisions about the best care for patients

with specific diseases or clinical conditions for which

medications are frequently recommended. The urge

for increased prescribing gives rise to medication-related

problems, which are particularly problematic

in elderly patients because of their tendency to have

multiple co-morbidities and age-related changes

in pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics. The

resultant polypharmacy seems to be unavoidable

nowadays, and it is often associated with potentially

inappropriate medications (PIM) and adverse drug

events. Furthermore, medication adherence is

insufficient in elderly patients. All of these factors

predispose patients to adverse health outcomes,

which deviate from the original intention of

therapeutic benefit but produce morbidity and

mortality with hospitalisation1 2 and increase the

social health cost.

Appropriate medication management with

reduction of polypharmacy, reduction of use of

inappropriate medications, and improvement of

medication adherence is relevant to optimisation

of older patients’ care. Because older people are

highly heterogeneous in terms of co-morbidities,

functional state, and psychosocial aspects, clinical and medication management should be

individualised. The principle of prescribing to older

people should weigh the clinical benefits against the

risks of medication therapies or overprescribing to

address the patients’ individual care goals, current

functioning level, social support, life expectancy,

values, and preference.

This article starts with case scenarios in each

section to illustrate and discuss the medication-related

problems of polypharmacy/inappropriate

medications, adverse drug events and prescribing

cascade, medication non-adherence, and post-discharge

medication discrepancy. These are followed

by patient-centred measures that recommend

prioritisation of treatment, deprescribing, and use of

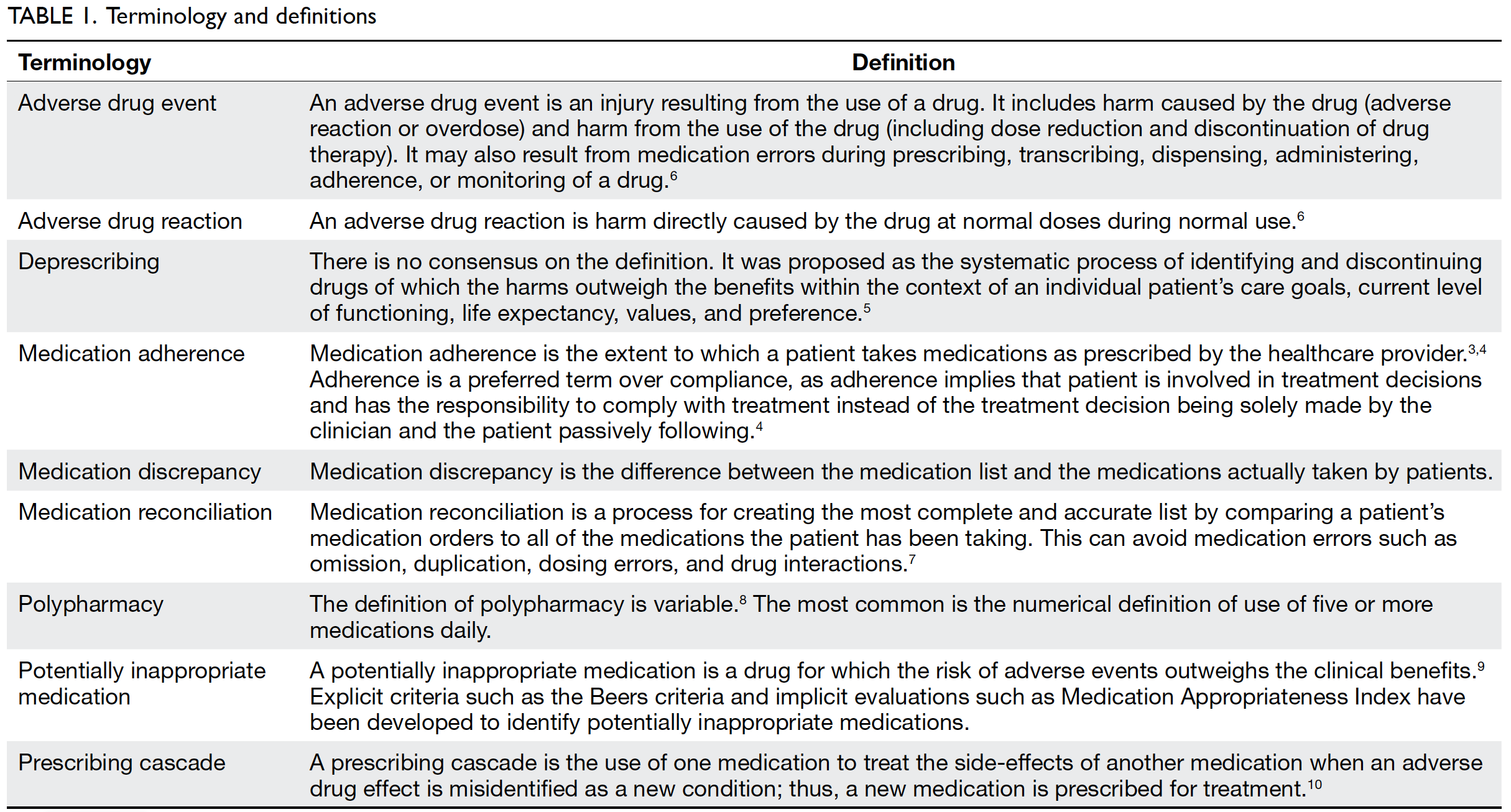

a multidisciplinary approach. Table 1 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 summarises

the terms mentioned in this article with definitions.

Polypharmacy and potentially

inappropriate medications

Case scenario 1

An 80-year-old woman had hypertension, diabetes

mellitus, and ischaemic heart disease. She had

17 medications on her prescription list: aspirin,

famotidine, amlodipine, methyldopa, enalapril,

gliclazide, metformin, simvastatin, enalapril,

isosorbide, frusemide, potassium chloride, and

as-needed drugs (betahistine, chlorphenamine,

cocillana, benadryl expectorant, and zopiclone). She strongly refused medications tapering during

follow-up at an out-patient clinic because of fear

of worsening blood pressure control, feet oedema,

dizziness, coughing, and insomnia. She was recently

admitted because of dizziness and fall, found to have

low blood pressure of 108/50 mm Hg and a heart

rate of 90 beats per minute, mild dehydration with

hyperkalaemia (urea 7.8 mmol/L, creatinine 60 μmol/L,

sodium 144 mmol/L, potassium 4.8 mmol/L) and

vitamin B12 deficiency (100 pmol/L).

Case scenario 2

A 75-year-old man had benign prostatic hyperplasia

and was taking terazosin. He developed herpes zoster

with postherpetic neuralgia, and amitriptyline was

prescribed. He then developed retention of urine.

Multiple co-morbidities are often prevalent

among older people. In Hong Kong, older patients

attending specialist out-patient clinics had an

average of four to five co-morbidities.11 With new

drugs and clinical guidelines being developed for

each disease, the number of medications taken by

individual patients is increasing. The mean number of

medications prescribed per patient were six and nine

in out-patient and in-patient settings, respectively.11 12 13

Using the concurrent use of five or more daily

medications to define polypharmacy, as many as

77.8% of older patients in Hong Kong had the burden

of polypharmacy, which was more than double the

corresponding proportion of 32% from two decades

ago,12 14 and 11% took 10 or more medications.11

Polypharmacy is positively associated with PIM

and subsequent adverse drug events, drug–drug

interactions, and drug–disease interactions.11 14 15 16

Potentially inappropriate medications are not solely

attributable to inappropriate prescribing but are

also related to changes in the benefits and risks of

a medication with time: medications can become

inappropriate for a given patient even if they were

previously appropriate. Approximately 30% to 59%

of patients in Hong Kong have been found to be

taking at least one inappropriate medication.11 12 13

The most common causes of inappropriateness

were medications without clear indications, lack of

effectiveness, incorrect dosage, difficult instructions,

unacceptable duration of therapy, and high cost in

comparison to alternatives of equal efficacy and

safety.13 Very often, it is difficult to measure the direct influence of inappropriate medications

on the patient and healthcare system. The non-specific

symptoms and geriatric syndromes caused

by inappropriate medications include fatigue,

dizziness, falls, urinary incontinence, and functional

or cognitive decline. These might be disregarded as

being related to ageing, making adverse drug events

difficult to recognise.15 16 Nonetheless, inappropriate

medications would potentially increase adverse

drug events or reactions with increased morbidity,

hospitalisation, and healthcare cost.17 18 19

Screening for potentially inappropriate

medications

Since polypharmacy are difficult to avoid nowadays,

the practical way to deal with is to enhance

appropriate use of medications with reduction

of PIM. Criteria and evaluation processes have

been developed to screen for PIM in older people.

Most are explicit criteria based on trial evidence,

systematic reviews, expert panel suggestions, and

consensus evaluation with the aims of improving

medication appropriateness and minimising adverse

drug events and subsequent hospitalisation. The

most widely used explicit prescribing criteria are

the Beers criteria and the Screening Tool of Older

Person potentially inappropriate Prescriptions

(STOPP)/Screening Tool to Alert doctors to the

Right Treatment (START) criteria.

The Beers criteria were designed for use in

people aged 65 years or older in ambulatory, acute,

and institutionalised settings but not for those

receiving hospice or palliative care.20 The Beers

criteria have undergone review and been updated

regularly since first being published in 1991. The

most updated version, the Beers 2019 criteria,21 lists

PIMs to be avoided in five categories: (1) Drugs and

drug classes to avoid; (2) Drugs and drug classes to

avoid in certain diseases or syndromes; (3) Drugs to

be used with caution; (4) Drug–drug interactions

that should be avoided; and (5) Drugs to be avoided

or dosage reduced in cases with kidney disease. Each

criterion stated is supplemented by the rationale for

the recommendation, level of evidence, and strength

of the recommendation.

The STOPP/START criteria provide

prescribing guidance tailored for older people

aged 65 years or older.22 Like the Beers criteria, the

STOPP criteria comprise a list of PIMs. In addition, a list of potential prescribing omissions

(START criteria) alert clinicians about appropriate

and indicated prescribing. Instead of listing the

offending drugs, the STOPP/START criteria outline

clinical circumstances with each criterion to

address the drug or drug class that is deemed to be

inappropriate or drugs that should be considered, so

they are considered to be more relevant in clinical

practice. The STOPP/START criteria have also been updated to maintain their clinical relevance: the

latest edition (version 2) was published in 2015.23

These explicit criteria provide only evidence-based

references but do not address individual

patients’ circumstances, such as co-morbidities and

preference. Therefore, they cannot replace clinical

judgement about patient-centred decisions but can

alert clinicians to potential instances of inappropriate

medication use.

Implicit evaluation, in contrast, is judgement-based

and focused on patients rather than drugs or

diseases. The Medication Appropriateness Index

is one set of implicit tool and is frequently used in

research.24 It includes 10 items to determine the

appropriateness of a given medication: indication,

effectiveness, correct dosage, practical direction,

drug–drug interactions, drug–disease interactions,

duplication, acceptable duration, and expense. “Yes”

or “No” is applied for each item in which “Yes” scores

0 whereas “No” scores from 1 to 3 depending on its

importance in the assessment of the appropriateness

of a given drug with indication and effectiveness are

given most weigh. A total score is then generated

with higher scores indicating more inappropriate

medications. Although these evaluation processes

are patient-centred and address the entire medication

regimen, their applicability is limited by the fact that

they are time-consuming and dependent on the

clinician’s knowledge and experience.

Remarks

Scenario 1 illustrated polypharmacy with the adverse

outcomes of dizziness and fall. The inappropriate

medications prescribed were those with no clear

indications or questionable effectiveness, or for

the treatment of a drug adverse reaction, such

as frusemide (STOPP criteria) for feet oedema,

which was possibly related to the adverse effects

of amlodipine; benadryl and cocillana for cough,

which were possibly related to the adverse effects of

enalapril; and betahistine for dizziness, which was

possibly related to methyldopa (STOPP and Beers

criteria) and vitamin B12 deficiency as a result of long-term

metformin intake. Medications were adjusted

by replacing enalapril with losartan, replacing

methyldopa and amlodipine with metoprolol

for blood pressure control and ischaemic heart

disease (START criteria), and adding a vitamin B12

supplement. The patient was tapered off frusemide,

potassium chloride, and all as-needed medications.

In scenario 2, prescribing amitriptyline (which

has strong anticholinergic properties) to an elderly

man with benign prostatic hypertrophy is considered

to be inappropriate (Beers and STOPP criteria), as

it could precipitate urinary retention, and there are

alternatives with fewer anticholinergic effects. For

example, gabapentin can be chosen for postherpetic

neuralgia.

Adverse drug events and

prescribing cascade

Case scenario 3

A 70-year-old man had behavioural psychological

symptoms of dementia and was prescribed

memantine, sertraline, quetiapine, and lorazepam.

Because of fall with back pain, paracetamol and

tramadol were prescribed. He developed nausea and

vomiting, and then metoclopramide was given. Later,

he developed fever, restlessness, and limb rigidity.

Serotonin syndrome as a result of concomitant use

of sertraline, tramadol, and metoclopramide was

suspected.

Adverse drug events are common in clinical

practice. Large-scale studies have found overall

rates of adverse drug events of 50.1 per 1000

person-years in ambulatory older people and 1.89

per 100 person-months in institutionalised elderly

residents.25 26 The most commonly implicated agents

were cardiovascular drugs in the ambulatory setting

and antipsychotics in the institutional setting, which

might be related to the frequent use of these drugs in

those corresponding settings. Accordingly, the most

common types of adverse events were electrolyte/renal, gastrointestinal tract, and haemorrhage events

in ambulatory patients, whereas neuropsychiatric

events (oversedation, confusion, hallucinations,

delirium) predominated in the institutional setting.

Up to 51% of the observed adverse drug events were

preventable, and serious, life-threatening and fatal

events were more likely to be preventable than were

less severe events.25 26 The errors associated with those

preventable events most commonly occurred at the

stages of prescribing and monitoring. Prescribing

errors included wrong dosage, significant drug

interactions, and wrong choice of drugs (eg, using

drugs with significant anticholinergic effects instead

of safer alternatives). Monitoring errors refer to

inadequate laboratory monitoring, delayed response

or failure to respond to signs and symptoms, and/or

laboratory evidence of toxicity.

Adverse drug events or reactions may

precipitate a prescribing cascade. Prescribing cascade

occurs when adverse drug events are mistaken as a

new medical condition and leads to addition of new

drugs for treatment.10 It places patients at risk of

developing additional adverse drug events because

of the potentially unnecessary treatment. Adverse

consequences of prescribing cascade include

polypharmacy and its associated adverse event as

in Case 1 (see Case 1 remarks), and exacerbation of

the harmful effects of adverse drug reactions as in

Case 3, serotonin syndrome resulted from the use of

serotonin reuptake inhibitors together with tramadol

and metoclopramide. In addition to the drugs

involved in Cases 1 and 3 (amlodipine, angiotensin-converting

enzyme inhibitor, serotonin reuptake inhibitor, and tramadol), other common drugs

implicated in prescribing cascade are cholinesterase

inhibitors which cause urinary incontinence with

subsequent oxybutynin added, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory

drugs which cause or exacerbate

hypertension with antihypertensive agent added, and

antipsychotic agents which cause extrapyramidal

sign with levodopa or anticholinergic added.27 They

are largely preventable provided that clinicians are

aware of this during the prescribing process.

Preventing adverse drug events and

prescribing cascade

Provided that a significant proportion of adverse drug

events and common sources of error are preventable,

adverse drug events are amenable to prevention

strategies. Computerised order entry is widely used

nowadays to alert prescribers about the drug dosage,

need for dose adjustment according to renal function,

potential drug interactions, or allergic reactions,

and this significantly reduces medication errors.28

However, this cannot replace clinical judgements

about relevant indications, correct drug choices, and

simplification of medication regimens. Regular review

to obtain an updated medication list is good practice,

especially when a new prescription or change in

prescription is instituted. Whenever a new symptom

occurs, assessment to rule out adverse effects from

currently taken medications to prevent a ‘prescribing

cascade’, or adding drugs to treat other drugs’ adverse

effects, should be considered. Non-pharmacological

therapies could be effective alternatives to replace

some psychoactive medications.29 The development

of a systematic approach based on patient-centred

care to facilitate decision-making about prescribing

certain medications to frail, elderly patients (eg,

anticoagulants) and subsequent monitoring

is anticipated. Furthermore, enhancement of

surveillance and reporting systems for adverse drug

events with subsequent analysis and correction of the

underlying systematic faults could achieve significant

error reduction.30

Remarks

In scenario 3, the series of adverse drug events

and the serious medical consequence of serotonin

syndrome was preventable if the prescribing cascade

had been broken by minimising medications for the

behavioural psychological symptoms of dementia,

such as stopping quetiapine or lorazepam for fall

risk at the initial stage or stopping tramadol to treat

the adverse drug reaction of nausea and vomiting

instead of giving metoclopramide at a later stage.

Medication adherence

Case scenario 4

A 76-year-old man had paroxysmal supraventricular

tachycardia, for which he had been prescribed sotalol, and iatrogenic Cushing syndrome, for which he was

on hydrocortisone replacement. He was admitted for

a supraventricular tachycardia attack. He admitted

that he did not take sotalol because of fatigue and low

heart rate and took hydrocortisone only occasionally

because of facial puffiness.

Case scenario 5

A 79-year-old woman lived alone and was referred to a

community nurse for medication management. Many

drug stocks were found in her home. She was suspected

to have cognitive impairment on initial assessment.

Poor medication adherence is common in

clinical practice, with a 50% adherence rate observed

among patients with chronic conditions.3 Poor

medication adherence is even more problematic

in elderly people because they may have decreased

functionality and cognitive impairment. Because of

the differences in measurement methods used and

the settings of the studied populations, the prevalence

of medication non-adherence among elderly patients

has varied widely in local studies (9%-54%).31 32 33

Medication non-adherence leads to drug waste and

treatment failure, with resultant hospitalisation

and increased healthcare cost. It may also prompt

inappropriate increases in drug dosage, addition

of or changes to more potent drugs, and increased

risk of adverse drug events if it is unrecognised and

regarded as poor response to treatment.

There are many ways to assess medication

adherence, such as measuring medication or their

metabolite levels in blood, using questionnaires or

self-reports, and pill counting. Nonetheless, the

simplest and most direct method is asking the patient

nonjudgmentally about how often they miss doses

and encouraging them to talk about their difficulties

with medication management.4 Barriers to poor

medication adherence are multifactorial and can

generally be categorised into prescriber-related (eg,

poor communication or relationship with patients,

lack of time for patient education), patient-related (eg,

poor knowledge, fear of adverse reactions, depression,

diminished physical or mental capacity), medication-related

(eg, polypharmacy, complexity of medication

regimen), and poor social support.3 34 35 Common

factors related to poor medication adherence in studies

have included adverse drug events,32 33 35 complicated

drug regimen,32 33 35 36 recent changes in medication

regimen,37 and multiple morbidities or self-perceived

poor health.31 35 36 Because both cognitive impairment

and depression are prevalent among elderly patients,

and these conditions can impede functionality and

thus medication management, these two conditions

should be looked for in older patients with poor

medication adherence.31 35 36

Improving medication adherence

As poor medication adherence is often multifactorial, a multidimensional approach is required. In general,

such an approach includes patient education,

enhancing clinician–patient communication,

improving medication regimens, and facilitating

social support. Providing education to the patient and

their family members or caregivers on medication-and

disease-related information, indications and

adverse reactions of the medications prescribed, and

how to handle the regimen is effective for improving

adherence.38 Besides, enhancing communication by

listening to the patient or caregiver’s concerns and

formulating a compromised treatment plan can

encourage adherence.4 Furthermore, encouraging

the patient to participate in disease management,

such as self-monitoring of blood pressure or blood

glucose, can also enhance adherence.4 Simplification

and regular review of the medication regimen should

be emphasised.31 38 Older patients with suspicion

of cognitive impairment or depression should be

assessed for management. Family members of

patients with cognitive impairment, mood disorders,

or decreased functionality are encouraged to assist

in medication management.31 32 For those with poor

family support, social support from, eg, a community

nursing service to assist in packing medications

with use of medication boxes or charts can also be

helpful.32 38 Reinforcement of the above strategies

and assessment of adherence should be performed

continuously to maintain adherence.

Remarks

In scenario 4, adverse drug reactions resulted

in poor medication adherence. After education

and explanation about his medical condition and

medication indications, and after his concerns were

addressed, the patient agreed to take hydrocortisone

and resumed low-dose sotalol with regular review at

follow-up clinic.

In scenario 5, cognitive impairment impeded

proper drug management. Patients with poor social

support, poor disease control, and many drug stocks

at home should have a high index of suspicion.

The drug regimen was simplified to once/day, and

the patient was referred for cognitive assessment,

management, and social support.

Post-hospital discharge

medication discrepancies

Case scenario 6

An 80-year-old woman complained of dizzy spells,

and she had a blood pressure of 87/39 mm Hg and a

pulse of 50 beats per minute at follow-up clinic. She

had recently been hospitalised for congestive heart

failure, and her medications were adjusted (atenolol

was replaced by carvedilol, and ramipril and

frusemide were added). However, she did not notice

that the medications had been adjusted and took all of the previous medications together with the newly

prescribed medications.

Sometimes, it is not the patient’s intention not

to follow the medication instructions, but they may

not notice or may misunderstand the changes in

their medication regimen. Such errors often occur at

the time of hospital discharge, as hospital admission

typically results in adjustments to medication

regimens. Discrepancies between the medications

listed on discharge instructions and the medications

actually taken by patients were found in up to half

of patients following hospital discharge.39 40 Older

patients are particularly at risk, with fewer than

10% of community-dwelling older patients adhering

completely to their discharge medication lists in one

study.41 Medication discrepancies include addition/duplication or omission of medications and changes

to dosing or frequency. This might endanger patients’

health because of adverse drug events or suboptimal

disease control. One study found that 14% of older

patients with medication discrepancies were re-hospitalised

at 30 days after hospital discharge.42

The discharge process is often criticised for

its contribution to medication discrepancy. Poor

clinician–patient communication, the lack of or

incomplete review of medication regimen, or failure

to inform the patient about medication changes

upon discharge are often blamed as causes.43

In addition, inaccurate discharge medication

instructions, such as duplication, omission,

incorrect dosage or frequency of medications, and

unclear prescribing instructions are commonly

encountered.40 42 44 Discharge medication lists that

are not integrated with medications the patient took

from other specialties before admission may cause

confusion as to whether the patient should continue

to take those prior medications or adjust their

dosages after discharge. Patients at high risk of post-discharge

medication discrepancy include those

with depression,39 impaired cognitive function or

low medication literacy (ie, difficulty understanding

medication-related information),39 40 and those

who receive multiple medications or complicated

regimens.41 42

Minimising post-discharge medication

discrepancy

Improvement of the hospital discharge process

is the first and most important step to improve

medication adherence and reduce preventable

post-hospitalisation complications. Medications

reconciliation to construct an integrated discharge

medication list, which combines medications

adjusted during hospitalisation and those from

other specialties, is recommended.45 In addition,

reminders to the involved clinicians from other

departments about the changes to medications

previously prescribed by them are suggested. Counselling and education for patients and their

families or caregivers about the new regimen of

medications with focus on medication changes

from pre-admission and high-risk medications (eg,

warfarin and insulin) could promote adherence and

medication safety after discharge.46 Post-discharge

surveillance by phone contact with patients to

address post-discharge problems or answer questions

has been found to be beneficial.45 Arrangements

for early follow-up can help with monitoring post-hospitalisation

medication adherence, adverse

effects, and prescribing mistakes.

Remarks

Medication incidents similar to those in scenario 6

could be avoided with better communication

highlighting the adjusted medications upon discharge.

Prioritisation of disease

management

Case scenario 7

A 60-year-old man had metastatic lung carcinoma

and opted for palliative care. Other medical history

included diabetes mellitus, hypertension, and

cerebrovascular disease. He had cachexia, pain,

dyspnoea, and poor oral intake. Medications included

morphine, metoclopramide, senokot, enalapril,

metformin, gliclazide, simvastatin, aspirin, and

pantoprazole.

Patient-centred care has increasingly

emphasised addressing the needs of individual

patients to maintain their quality of life and

functioning.45 The goal of care should be

individualised, taking into account the disease’s

impact on both the patient’s short- and long-term

health, the patient’s circumstances, and their

preference. Patient-centred care identifies the

patient’s clinically dominant condition to determine

the priority of care. This can guide medication use

towards the area most important to the patient and

reduce or stop medications that are less meaningful

to their health status. In scenario 6, a patient with

multiple co-morbidities had been diagnosed

with metastatic carcinoma and had a limited life

expectancy. Both the patient and their family opted for

palliative care (goal of care), and their main concerns

were pain and shortness of breath (clinical dominant

condition). Proper control of these distressing

symptoms should be the priority. In addition to

non-pharmacological therapy, medications should

be adjusted for symptomatic relief. Medications for

other chronic conditions, such as diabetes mellitus

and cerebrovascular disease, should be minimised, as

the potential benefits would likely not be observed,

but there would be increased drug interactions and

adverse events (eg, hypoglycaemia, poor appetite,

bleeding).

Deprescribing

Case scenario 8

A 90-year-old woman with right middle cerebral

artery infarction was discharged to a residential

home. She was bedbound, non-communicable,

and totally dependent. Her medications included

warfarin, amlodipine, simvastatin, lansoprazole,

donepezil, haloperidol, and quetiapine.

Deprescribing is increasingly considered as a

part of good clinical practice. Through the process

of medication review to withdraw medications that

are no longer appropriate or to taper medications

to the minimum effective dosage, the benefits and

risks of medications can be balanced according to

the patient’s current health status. Deprescribing is

particularly relevant to patients with the burden of

polypharmacy or changing clinical conditions. The

evidentiary base for deprescribing in older people

is growing. Systematic reviews have demonstrated

that carefully selecting patients to undergo planned

medications withdrawal had no detrimental effects in

a substantial proportion of older people.47 48 49 Common

drug classes studied in medication withdrawal trials

are antihypertensive agents, benzodiazepines, and

psychotropic agents. The benefits of discontinuation

of these medications is not limited to polypharmacy

reduction but also include reduced fall risk and

improved cognition and psychomotor function.47 48 49

Although deprescribing is generally regarded

as feasible and safe, fear of rebound or return of

symptoms and exacerbation of underlying conditions

are the major barriers to prescribing. There are

practical guides and algorithms to assist with the

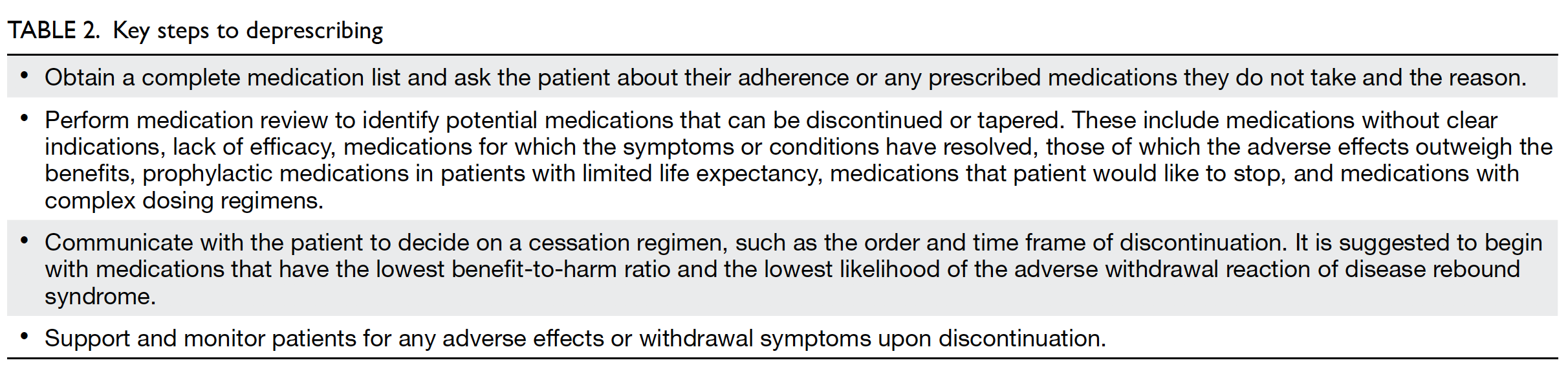

deprescribing process.5 50 51 All highlight that it is a

supervised process. Table 2 shows the key steps to

deprescribing.

Besides the general approach to deprescribing,

there is medication class-based guidance on how to

taper particular medications. There are evidence-based

guidelines that provide the reasons for and

benefits of deprescribing an identified medication,

recommendations on how to taper or stop, the

period and symptoms to monitor, non-medication

approaches for management of symptoms, and instructions if symptoms relapse.52 53 The medication

classes considered as high priority for deprescribing

in older patients are those with high prevalence of

use or overtreatment, significant adverse effects,

other effective treatment options available, or those

that are easy to stop. These medication classes

include antipsychotics, statins, benzodiazepines,

proton pump inhibitors, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory

drugs, furosemide, antihypertensive

agents, antihyperglycaemic agents, cholinesterase

inhibitors, and memantine.51 52 53 54

Patients or caregivers who are reluctant or

disagree with medications cessation are common.

Such attitudes negatively influence the success of

deprescribing. The reasons against medications

cessation include patients’ perceptions that the

medications are necessary or beneficial and their

fears of worsening clinical conditions or withdrawal

effects, especially if they had previous bad

experiences with medication cessation.55 Another

barrier is the limited consultation time and lack

of support from clinicians.55 A stepwise approach

with time given for shared decision-making about

deprescribing is reasonable.51 Such an approach

starts with patient or caregiver education on the

purpose of deprescribing, including exploration of

and addressing their concerns. Then, options should

be provided with respect to medication tapering,

non-pharmacological interventions, and monitoring

for adverse withdrawal effects, and reassurance

should be given that the discontinued medications

can be restarted if needed. A multidisciplinary

approach with the clinician being supported by other

healthcare professionals can relieve time pressure

during consultations. Patients with depression and

anxiety disorders may need treatment for their

psychiatric conditions before they can participate in

deprescribing.

Remarks

The patient in scenario 8 was non-communicable and

totally dependent. Anticoagulants and simvastatin,

which no longer provided cardiovascular/cerebrovascular benefits, and donepezil, which no longer provided cognitive benefits, were tapered off.

Haldol and quetiapine were also tapered off because

of the patient’s lack of disturbing behaviour.

Multidisciplinary team approach

A multidisciplinary team approach is recommended

to optimise medication management and treatment

decisions, minimise adverse drug effects, enhance

medication safety, and promote medication

adherence.45 56

Clinician

The clinician plays a central role in prescribing

and the subsequent medication-related problems.

The following points are recommended to improve

clinicians’ medication management for older

patients:

Pharmacist

The role of the pharmacist in the healthcare system is

expanding from dispensing service to direct patient

care. Pharmacists can help with medication-related

problems in different settings.13 57 58 59 Polypharmacy

and inappropriate medications: the pharmacist can

check the appropriateness of medications to make

recommendations for clinicians; Non-adherence:

the pharmacist can check the patient’s medication

adherence or discrepancy, provide counselling,

identify the patient’s difficulties, and communicate

with clinicians to modify the medication regimen.

Pharmacists provide both in-patient and out-patient

service, the latter in the form of pharmacist-led

drug compliance clinics, and their services further

extend to the community through public-private

partnerships.

Although the results of studies on the efficacy

of clinical pharmacy service are equivocal,58 pharmacists’ positive impact cannot be denied, as

those equivocal results are probably related to the

complexity of pharmacists’ interventions and the lack

of an evaluation standard in studies. Nonetheless, a

recent local study on a pharmacist-led medication

review programme for hospitalised elderly patients

that included medication reconciliation, medication

review, and medication counselling showed

significantly reduced numbers of inappropriate

medications and unplanned hospital admissions.13

Another local study also demonstrated a positive

impact of pharmacists on identifying, resolving, and

preventing medication-related problems.59

Nurse

Besides administering medications, nurses are also

involved in medication care for older patients in the

following ways:

Conclusion

Numerous studies have shown that medication-related

problems (eg, polypharmacy, inappropriate

medication, adverse drug events, medication non-adherence,

and medication discrepancy) are common

in older patients. Strategies or interventions such

as screening tools for inappropriate medications,

deprescribing, and multidisciplinary approaches

have been introduced to optimise medication

management. However, helping patients to take

medications safely and effectively is still challenging.

Very often, we are aware of the problem, but it is

difficult to alter or deal with, as there are multiple

barriers (eg, pressure from patients/caregivers, short

consultation time). Thus, in addition to continuous

education, reminding clinicians about appropriate

prescribing, regular review, and medication regimen

adjustment, public education to promote the

rational use of medications is important. Continuing to review and address the effects of deficiencies in

the healthcare system on medication safety could

lead to a reduction in medication-related problems

with time.

Author contributions

The author contributed to the concept or design of the study,

acquisition of the data, analysis or interpretation of the

data, drafting of the manuscript, and critical revision of the

manuscript for important intellectual content. The author had

full access to the data, contributed to the study, approved the

final version for publication, and takes responsibility for its

accuracy and integrity.

Conflicts of interest

The author has disclosed no conflicts of interest.

Funding/support

This research received no specific grant from any funding

agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

References

1. Lazarou J, Pomeranz BH, Coret RN. Incidence of adverse

drug reactions in hospitalized patients: a meta-analysis of

prospective studies. JAMA 1998;279:1200-5. Crossref

2. Davies EC, Green CF, Taylor S, Williamson PR, Mottram DR,

Pirmohamed M. Adverse drug reactions in hospital in-patients:

prospective analysis of 3695 patient-episodes.

PLoS One 2009;4:e4439. Crossref

3. World Health Organization. Adherence to

long term therapies: evidence for action. 2003.

Available from: https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/42682/9241545992.pdf. Accessed 23 Nov

2020.

4. Osterberg L, Blaschke T. Adherence to medication. N Engl J Med 2005;353:487-97. Crossref

5. Scott IA, Hilmer SN, Reeve E, et al. Reducing inappropriate

polypharmacy: the process of deprescribing. JAMA Intern

Med 2015;175:827-34. Crossref

6. VA Centre for Medication Safety, VHA Pharmacy

Benefits Management Strategic Healthcare Group,

Medical Advisory Panel. Adverse drug events, adverse

drug reactions, medications error. Frequently asked

questions. November 2006. Available from: https://www.pbm.va.gov/PBM/vacenterformedicationsafety/tools/AdverseDrugReaction.pdf. Accessed 23 Nov 2020.

7. The Joint Commission. National patient safety goals

effective July 2020 for the ambulatory health care program.

Available from: https://www.jointcommission.org/-/media/tjc/documents/standards/national-patient-safety-goals/2020/npsg_chapter_ahc_jul2020.pdf. Accessed 23

Nov 2020.

8. Masnoon N, Shakib S, Kalish-Ellett L, Caughey GE. What is polypharmacy? A systematic review of definitions. BMC

Geriatr 2017;17:230. Crossref

9. Corsonello A, Pranno L, Garasto S, Fabietti P, Bustacchini S, Lattanzio F. Potentially inappropriate medications in elderly

hospitalized patients. Drugs Aging 2009;26 Suppl 1:31-9. Crossref

10. Rochon PA, Gurwitz JH. Optimising drug treatment

for elderly people. The prescribing cascade. BMJ

1997;315:1096-9. Crossref

11. Lam DP, Mak CF, Chan SM, Yao RW, Leung SS, You JH.

Polypharmacy and inappropriate prescribing in

elderly Hong Kong Chinese patients. J Am Geriatr Soc

2010;58:203-5. Crossref

12. Lam MP, Cheung BM, Wong IC. Prevalence of potentially

inappropriate prescribing among Hong Kong older adults:

a comparison of the Beers 2003, Beers 2012, and screening

tool of older person’s prescriptions and screening tool to

alert doctors to right treatment criteria. J Am Geriatric Soc

2015;63:1471-2. Crossref

13. Chiu P, Lee A, See T, Chan F. Outcomes of a pharmacist-led

medication review programme for hospitalised elderly

patients. Hong Kong Med J 2018;24:98-106.

14. Ko CF, Ko PS, Tsang ML. A survey on the polypharmacy

and use of inappropriate medication in a geriatric

outpatient clinic. J HK Geriatr Soc 1996;7:28-31.

15. Maher RL, Hanlon J, Hajjar ER. Clinical consequence of polypharmacy in elderly. Expert Opin Drug Saf 2014;13:57-

65. Crossref

16. Hajjar ER, Cafiero AC, Hanlon JT. Polypharmacy in elderly

patients. Am J Geriatr Pharmacother 2007;5:345-51. Crossref

17. Onda M, Imai H, Takada Y, Fujii S, Shono T, Nanaumi Y.

Identification and prevalence of adverse drugs events

caused by potentially inappropriate medication in

homebound elderly patients: a retrospective study using

a nationwide survey in Japan. BMJ Open 2015;5:e007581. Crossref

18. Fu Az, Liu GG, Christensen DB. Inappropriate medication

use and health outcomes in the elderly. J Am Geriatr Soc

2002;52:1934-9. Crossref

19. Laroche ML, Charmes JP, Nouaille Y, Picard N, Merle L. Is

inappropriate medication use a major cause of adverse drug

reactions in the elderly? Br J Clin Pharmacol 2007;63:177-86. Crossref

20. American Geriatrics Society 2015 Beers Criteria Update

Expert Panel. American Geriatrics Society 2015 updated

Beers Criteria for potentially inappropriate medication use

in older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc 2015;63:2227-46. Crossref

21. American Geriatrics Society 2019 Beers Criteria Update

Expert Panel. American Geriatrics Society 2019 updated

AGS Beers Criteria for potentially inappropriate medication

use in older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc 2019;67:674-94. Crossref

22. Gallagher P, Ryan C, Byrne S, Kennedy J, O’Mahony D.

STOPP (Screening Tool of Older Person’s Prescriptions)

and START (Screening Tool to Alert doctors to Right

Treatment). Consensus validation. Int J Clin Pharmacol

Ther 2008;46:72-83. Crossref

23. O’Mahony D, O’Sullivan D, Byne S, O’Connor MN, Ryan C,

Gallagher P. STOPP/START criteria for potentially

inappropriate prescribing in older people: version 2. Age

Ageing 2015;44:213-8. Crossref

24. Hanlon JT, Schmader KE, Samsa GP, et al. A method for

assessing drug therapy appropriateness. J Clin Epidemiol

1992;45:1045-51. Crossref

25. Gurwitz JH, Field TS, Harrold LR, et al. Incidence and

preventability of adverse drug events among older persons

in the ambulatory setting. JAMA 2003;289:1107-16. Crossref

26. Gurwitz JH, Field TS, Avorn J, et al. Incidence and

preventability of adverse drug events in nursing homes.

Am J Med 2000;109:87-94. Crossref

27. Kalisch LM, Caughey GE, Roughead EE, Gilbert AL. The

prescribing cascade. Aust Prescr 2011;34:162-6. Crossref

28. Bates DW, Leape LL, Cullen DJ, et al. Effect of computerised

physician order entry and a team intervention on prevention of serious medication error. JAMA 1998;280:1311-6. Crossref

29. de Oliverira AM, Radanovic M, de Mello PC, et al.

Nonpharmacological interventions to reduce behavioural

and psychological symptoms of dementia: a systematic

review. Biomed Res Int 2015;2015:218980. Crossref

30. Leape LL. Error in medicine. JAMA 1994;272:1851-7. Crossref

31. Leung DY, Bai X, Leung AY, Lou BC, Chi I. Prevalence of

medication adherence and its associated factors among

community-dwelling Chinese older adults in Hong Kong.

Geriari Gerontol Int 2015;15:789-96. Crossref

32. Lam PW, Lum CM, Leung MF. Drug non-adherence and

associated risk factors among Chinese geriatric patients in

Hong Kong. Hong Kong Med J 2007;13:284-92.

33. Chong CK, Chan JC, Chang S, Yuen YH, Lee SC, Critchley JA.

A patient compliance survey in a general medical clinic. J

Clin Pharm Ther 1997;22:323-6. Crossref

34. Hale LS, Calder DR. Managing medication nonadherence.

In: Muma RD, Lyons BA, editors. Patient Education: a

Practical Approach. 2nd ed. Boston, MA: Jones & Barlett

Learning; 2012: 41-7.

35. Yap AF, Thirumoorthy T, Kwan YH. Systematic review of

the barriers affecting medication adherence in older adults.

Geriatric Gerontol Int 2016;16:1093-101. Crossref

36. Smaje A, Weston-Clark M, Raj R, Orlu M, Davis D, Rawle M.

Factors associated with medication adherence in older

patients: a systematic review. Aging Med (Milton)

2018;1:245-66. Crossref

37. Barber N, Parsons J, Clifford S, Darracott R, Horne R.

Patients’ problems with new medication for chronic

conditions. Qual Saf Health Care 2004;13:172-5. Crossref

38. Wilhelmsen NC, Eriksson T. Medication adherence

intervention and outcomes: an overview of systematic

reviews. Eur J Hosp Pharm 2019;26:187-92. Crossref

39. Mixon AS, Myers AP, Leak CL, et al. Characteristics

associated with post-discharge medications errors. Mayo

Clin Proc 2014;89:1041-51. Crossref

40. Lindquist LA, Go L, Fleisher J, Jain N, Friesema E,

Baker DW. Relationship of health literacy to intentional

and unintentional non-adherence of hospital discharge

medications. J Gen Intern Med 2012;27:173-8. Crossref

41. Mulhem E, Lick D, Varugese J, Barton E, Ripley T, Haveman J.

Adherence to medications after hospital discharge in the

elderly. Int J Family Med 2013;2013:901845. Crossref

42. Coleman EA, Smith JD, Raha D, Min SJ. Posthospital

medication discrepancies: prevalence and contributing

factors. Arch Intern Med 2005;165:1842-7. Crossref

43. Forster AJ, Murff HJ, Peterson JF, Gandhi TK, Bates DW.

The incidence and severity of adverse events affecting

patient after discharge from the hospital. Ann Intern Med

2003;138:161-7. Crossref

44. Caleres G, Modig S, Midlöv P, Chalmers J, Bondesson A. Medication discrepancies in discharge summaries and

associated risk factors for elderly patients with many drugs.

Drugs Real World Outcomes 2020;7:53-62. Crossref

45. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence, UK

Government. Medicines optimisation: the safe and

effective use of medicine to enable the best possible outcomes. NICE guideline [NG5]. 2015. Available from:

https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng5/chapter/1-Recommendations#medicines-related-models-of-organisational-and-cross-sector-working. Accessed 23

Nov 2020.

46. Kripalani S, Roumie CL, Dala AK, et al. Effect of

a pharmacist intervention on clinically important

medication errors after hospital discharge: a randomized

controlled trial. Ann Intern Med 2012;157:1-10. Crossref

47. Iyer S, Naganathan V, McLachlan AJ, Le Couteur DG.

Medication withdrawal trials in people aged 65 years and

older: a systematic review. Drugs Aging 2008;25:1021-31. Crossref

48. van der Cammen TJ, Rajkumar C, Onder G, Sterke CS,

Petrovic M. Drug cessation in complex older adults: time

for action. Age Ageing 2014;43:20-5. Crossref

49. Declercq T, Petrovic M, Azermai M, et al. Withdrawal

versus continuation of chronic antipsychotic drugs

for behavioural and psychological symptoms in older

people with dementia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev

2013;(3):CD007726. Crossref

50. Page AT, Potter K, Clifford R, Etherton-Beer C.

Deprescribing in older people. Maturitas 2016;91:115-34. Crossref

51. NHS Derby and Derbyshire. Clinical Commissioning Group.

Deprescribing: a practical guide. NHS 2019. Available

from: http://www.derbyshiremedicinesmanagement.nhs.uk/assets/Clinical_Guidelines/clinical_guidelines_front_page/Deprescribing.pdf. Accessed 23 Nov 2020.

52. McGrath K, Hajjar ER, Kumar C, Hwang C, Salzman B.

Deprescribing: a simple method for reducing

polypharmacy. J Fam Pract 2017;66:436-45.

53. Deprescribing.org. Deprescribing guidelines and

algorithms. Available from: https://deprescribing.org/resources/deprescribing-guidelines-algorithms/. Accessed

23 Nov 2020.

54. Farrell B, Tsang C, Raman-Wilms L, Irving H, Conklin J,

Pottie K. What are priorities for deprescribing for elderly

patients? Capturing the voice of practitioners: a modified

delphi process. PLoS One 2015;10:e0122246. Crossref

55. Reeve E, To J, Hendrix I, Shakib S, Roberts MS, Wiese MD.

Patient barriers to and enablers of deprescribing: a

systematic review. Drug Aging 2013;30:793-807. Crossref

56. Topinková E, Baeyens JP, Michel JP, Lang PO. Evidence-based

strategies for the optimization of pharmacotherapy

in older people. Drugs Aging 2012;29:477-94. Crossref

57. Bonetti AF, Reis WC, Mendes AM, et al. Impact of

pharmacist-led discharge counselling on hospital

readmission and emergency department visits: a systematic

review and meta-analysis. J Hosp Med 2020;15:52-9. Crossref

58. Renaudin P, Boyer L, Esteve MA, Bertault-Peres P,

Auquier P, Honore S. Do pharmacist-led medication

reviews in hospitals help reduce hospital readmission? A

systematic review and meta-analysis. Br J Clin Pharmacol

2016;82:1660-73. Crossref

59. Chung AY, Anand S, Wong I, et al. Improving medication

safety and diabetes management in Hog Kong: a

multidisciplinary approach. Hong Kong Med J 2017;23:158-67. Crossref