© Hong Kong Academy of Medicine. CC BY-NC-ND 4.0

COMMENTARY

Appendiceal endometriosis: a greater mimicker of

appendicitis

David H Jeong, MD; Hyojin Jeon, MD, MPH; Karen

Adkins, MD

Department of Surgery, Trinity School of Medicine,

Ribishi, Saint Vincent

Corresponding author: Mr David H Jeong (kb_1991@hotmail.com)

Endometriosis is defined as the presence of

functioning endometrial glandular cells outside the uterine cavity. It is

a common cause of pelvic pain that is worse during the menstruation cycle.

Endometriosis is extremely difficult to diagnose based on clinical

features, because the location of the ectopic endometrial cells could lead

to diagnosis of other common pathological causes of abdominal pain

specific to that area. Although some female patients remain asymptomatic,

endometriosis is usually associated with dysmenorrhea, chronic pelvic

pain, and infertility and can lead to bowel obstruction or abdominal mass.1

Although endometriosis within the uterine muscle

wall is commonly seen in about 10% of women of menstrual age, ectopy of

endometrial cells into the appendix is rare. The true prevalence of

extragenital endometriosis is unclear, owing to the lack of studies or

cases; the incidence of appendiceal endometriosis has been reported to be

as low as 0.054% and as high as 0.8%.2

Although endometriosis has been reported in almost any part of the human

body, to the best of our knowledge no cases have yet reported

endometriosis in the spleen.3

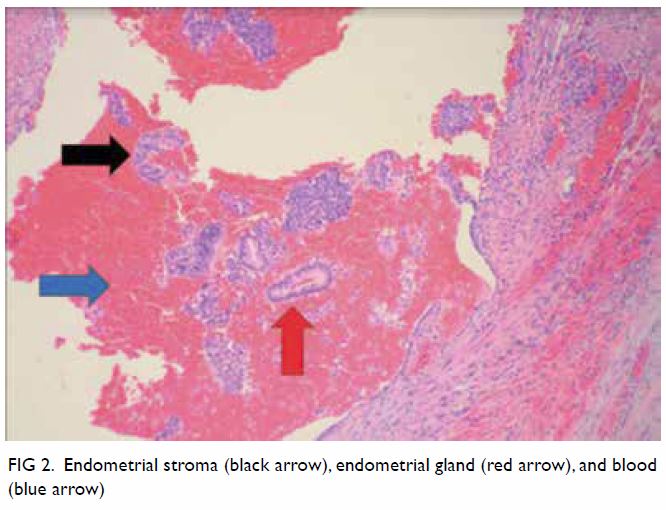

Appendiceal endometriosis is diagnosed

pathologically. The presence of glandular tissue, endometrial stroma, and

haemorrhage are typical findings in patients with endometriosis regardless

of the location.4 There is no

correlation between the location of the endometriotic foci and clinical

symptoms5 and endometriosis is much

likely to mimic primary inflammatory diseases. In the patient described in

this case report, ectopic endometrial cells mimicked inflammation inside

the appendiceal cavity and the patient presented with clinical symptoms

that were consistent with acute appendicitis.

In 2018, we experienced a 34-year-old woman who

presented with right lower quadrant abdominal pain for 1 day. The patient

described the localised pain as crampy and rated the pain severity as “10”

on a scale of 1 to 10. The patient presented with nausea, vomiting,

headache, constipation, menorrhagia, and dizziness. She also reported that

she was actively menstruating and that these symptoms typically occurred

monthly with menstruation, but had been particularly severe in that month.

The patient has two children and reported not using any form of

contraception. The patient’s medical history included inflammatory bowel

disease, migraine, chronic lower back pain, and asthma. The patient had a

Caesarean section delivery in 2000 and left fallopian tube/ovary removal

secondary to ruptured ectopic pregnancy in 2008. The patient denied use of

alcohol, tobacco, or illicit drugs. There was no relevant family history

of gastrointestinal diseases or malignancies and the patient was allergic

to morphine and azithromycin.

Physical examination showed mild distension of the

abdomen and tenderness to palpation on both right and left lower

quadrants. No rebounding tenderness or guarding was noted. Vital signs and

laboratory test results were all within normal limits with the exception

of slightly elevated white blood cell at 11.69 K/mm3. Although

5.32 M/mm3 of red blood cell was observed in the urinalysis,

the results were considered within normal limits since the patient was

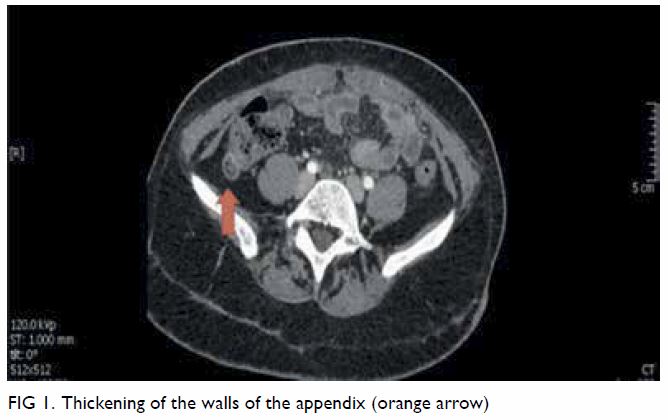

actively menstruating at the time of the test. Computed tomography scan of

the patient’s abdomen and pelvis (Fig 1) showed thick-walled appendix (>7 mm)

consistent with acute appendicitis.

The patient was taken to the operation room for

laparoscopic appendectomy. When the laparoscope was inserted inside the

patient’s abdominal cavity, significant adhesion of the entire abdominal

wall was noted. The appendix was unable to be visualised even after lysis

of adhesion was attempted using electrocautery. A decision was made to

proceed to open appendectomy. Further lysis of adhesions had to be done to

visualise the appendix, which did not show any gross inflammation. The

appendix was excised and sent to pathology lab for further investigation.

The appendix did not show any signs of

inflammation, and the preoperative diagnosis of acute appendicitis was

changed to possible endometriosis or ruptured cyst. However, 3 days after

the appendectomy, pathology results showed infiltration of endometrial

glands, endometrial stroma, and blood into the appendix (Fig

2). On the basis of these findings, appendiceal endometriosis was

finally diagnosed. After the appendectomy, the patient reported

substantial improvement of the right lower quadrant pain.

Appendiceal endometriosis is rare and its

preoperative diagnosis based on clinical features and/or imaging is

extremely difficult. Differential diagnosis in female patients who present

with acute pain in the right lower quadrant, especially those who are of

menstruating age, should include appendiceal endometriosis. Laparoscopy is

useful for the diagnosis since no gross inflammation is observed in the

appendix itself and appendectomy relieves the acute symptoms.

Author contributions

All authors contributed to the concept of study,

acquisition and analysis of data, drafting of the article, and critical

revision for important intellectual content. All authors had full access

to the data, equally contributed to the study, approved the final version

for publication and take responsibility for the accuracy and integrity of

the content.

Conflicts of interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest to

disclose.

Funding/support

This research has received no specific grant from

any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Ethics approval

The patient was treated in accordance with the

Declaration of Helsinki. The patient provided informed consent for all

procedures.

References

1. Yantiss RK, Clement PB, Young RH.

Endometriosis of the intestinal tract: a study of 44 cases of a disease

that may cause diverse challenges in clinical and pathological evaluation.

Am J Surg Pathol 2001;25:445-54. Crossref

2. Collins DC. A study of 50,000 specimens

of the human vermiform appendix. Surg Gynecol Obstet 1955;101:437-45.

3. Berker B, Lashay N, Davarpanah R,

Marziali M, Nezhat CH, Nezhat C. Laparoscopic appendectomy in patients

with endometriosis. J Minim Invasive Gynecol 2005;12:206-9. Crossref

4. Apostolidis S, Michalopoulos A,

Papavramidis TS, Papadopoulos VN, Paramythiotis D, Harlaftis N. Inguinal

endometriosis: three cases and literature review. South Med J

2009;102:206-7. Crossref

5. Uncu H, Taner D. Appendiceal

endometriosis: two case reports. Arch Gynecol Obstet 2008;278:273-5. Crossref