Hong Kong Med J 2019 Dec;25(6):453–9 | Epub 4 Dec 2019

© Hong Kong Academy of Medicine. CC BY-NC-ND 4.0

ORIGINAL ARTICLE

Uterine Fibroid Symptom and Health-related Quality of

Life Questionnaire: a Chinese translation and validation study

SY Yeung, FHKAM (Obstetrics and Gynaecology),

FHKCOG; Janice WK Kowk, BSc; SM Law, FHKAM (Obstetrics and Gynaecology), FHKCOG;

Jacqueline PW Chung, FHKAM (Obstetrics and Gynaecology), FHKCOG; Symphorosa SC Chan, FHKAM

(Obstetrics and Gynaecology), FHKCOG

Department of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, Prince of

Wales Hospital, The Chinese University of Hong Kong, Shatin,

Hong Kong

Corresponding author: Dr SY Yeung (carolyeung@cuhk.edu.hk)

Abstract

Introduction: The Uterine

Fibroid Symptom and Health-related Quality of Life (UFS-QOL)

questionnaire is a validated tool in English language to assess

treatment outcomes for women with fibroids. We performed a Chinese

(traditional) translation and cultural adaptation of it and evaluated

its reliability, validity, and responsiveness.

Methods: Overall, 223 Chinese

women aged ≥18 years with uterine fibroids self-administered the

UFS-QOL, Short-Form Health Survey-12, pictorial blood loss assessment

chart (PBAC), and a visual analogue scale (VAS) on fibroid-related

symptom severity. Demographics and haemoglobin levels were recorded;

physical examination and ultrasound for size of fibroids were performed.

Half of the women were followed up 6 months later for responsiveness.

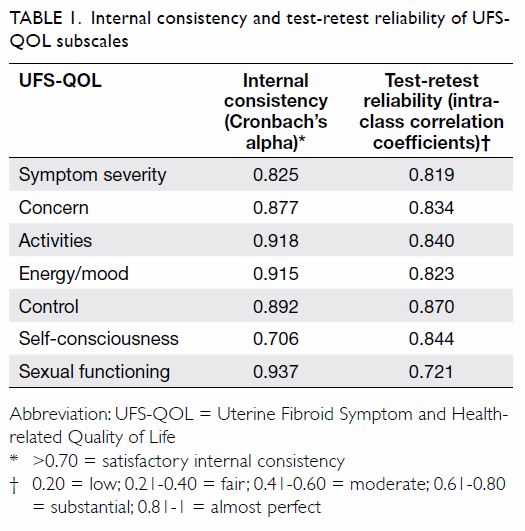

Results: Cronbach’s alpha

coefficients ranged from 0.706 to 0.937, demonstrating high internal

reliability. The intra-class correlation coefficients to measure

test-retest reliability implied excellent stability of symptom scores

(0.819, P<0.001), health-related quality of life scores (0.897,

P<0.001), and all subscales (range 0.721-0.870, P<0.001).

Convergent validity was demonstrated by positive correlations between

the findings of various symptom severity assessment tools (PBAC, VAS on

fibroid-related symptoms severity) and the symptom severity domain of

Chinese UFS-QOL. In addition, there were positive correlations between

health-related quality of life scores of Chinese UFS-QOL and the

corresponding subscales of the Short-Form Health Survey-12.

Responsiveness was shown by reduction of symptom severity scores and

improvement of health-related quality of life scores after treatment.

Conclusions: The Chinese version

of the UFS-QOL is valid, reliable, and responsive to changes after

treatment.

New knowledge added by this study

- The Chinese version of the Uterine Fibroid Symptom and Quality of Life Questionnaire (UFS-QOL) questionnaire is a valid and reliable tool to assess the impact of uterine fibroids on women’s quality of life, and it can be used to evaluate the response after treatment for uterine fibroids.

- The Chinese version of the UFS-QOL questionnaire can be used to evaluate the impact of uterine fibroids on quality of life to guide treatment and evaluate response during daily clinical practice. It is also a useful research tool to assess quality of life improvements after various fibroid treatments.

Introduction

Fibroids are the most common benign uterine tumour

affecting reproductive age women, and the lifetime risk is up to 60% in

women aged over 45 years.1 2 They are associated with menorrhagia,3 4 which results

in anaemia and reduced vitality.5

They also exert mass effects, leading to significantly increased urinary

frequency and stress urinary incontinence compared with the general

population.6 Moreover, women with

fibroids may experience deep dyspareunia.7

All the above have negative effects on quality of life.

Measuring the symptoms and quality of life of women

with fibroids is important, as it is a major indicator for treatment. The

Uterine Fibroid Symptom and Health-related Quality of Life Questionnaire

(UFS-QOL) is an English questionnaire published in 2002 that was specially

designed to assess the whole spectrum of fibroid-related symptoms and its

impact on quality of life.8 It

consists of eight items on symptoms and 29 on health-related quality of

life (HRQL) with six subscales (concern, activities, energy/mood, control,

self-consciousness, and sexual functioning). A raw score ranging from 1 to

5 is assigned to each of the items. To calculate the symptom severity

score and HRQL score, the sum of the raw scores of the related items is

transformed into a final score (range, 0-100) based on a specific formula.

A higher symptom severity score indicates more severe symptoms, while a

higher HRQL score indicates better quality of life. The UFS-QOL has been

validated, and its responsiveness was also assessed.8 9 10 It has been widely adopted in different studies to

assess fibroid treatment outcomes11

12 and translated into multiple

languages.13

The objective of this study was to produce a valid,

reliable, culturally adapted Chinese version of the UFS-QOL. We believe

this would serve as a useful tool to assess the impact of fibroid-related

quality of life and response to treatment and facilitate future research

and clinical use in the Chinese population.

Methods

Translation

We obtained approval to use the UFS-QOL from the

Society of the Interventional Radiology Foundation. A forward-backward

procedure was applied to translate the UFS-QOL into traditional Chinese.

Two independent bilingual researchers were asked to separately produce two

forward translations aiming for conceptual translation. The two

translations were reviewed between the two researchers to produce a

provisional draft of the Chinese UFS-QOL. The provisional Chinese UFS-QOL

was then back-translated to English by two other bilingual researchers who

were blinded to the original questionnaire. The back-translated English

version was further compared to the original questionnaire by two

monolingual experts (English) with no discrepancy noted before we

finalised the Chinese version of the UFS-QOL (online Supplementary Appendix)

Study phase

The study was conducted in the gynaecology clinic

of a university hospital between July 2015 and July 2016. All women aged

≥18 years with fibroids who understood written traditional Chinese were

eligible. Women with known mental incapacity or cognitive or developmental

disability were excluded. The Mini-Mental State Examination was performed

to detect and exclude women with unreported psychiatric morbidity. Written

consent was obtained.

Women were asked to fill out the Chinese UFS-QOL

and Short-Form Health Survey-12 (SF-12) before consultation. The SF-12 is

a 12-item survey that assesses eight domains of quality of life (physical

functioning, role limitation as a result of physical and emotional

problems, bodily pain, general health, vitality, social functioning, and

mental health), and it has a validated Chinese version.14 Lower SF-12 scores are associated with worse HRQL.

The participating women were assessed by

gynaecologists who were blinded to the questionnaire information. Clinical

and socio-demographic data including age, gravidity, parity, co-existing

medical illness, menstrual status, education level, marital status,

literacy, and employment status were obtained. General examinations to

examine the subjects for pallor and measure their blood pressure, pulse,

body weight, and height were performed. Abdominal and/or gynaecological

examinations were performed to assess the uterine size and rule out other

pathology. Transabdominal and/or transvaginal ultrasound were performed to

measure uterine size and the number, location, and size of fibroids.

Complete blood work was performed. Both the women and the attending

gynaecologists were asked to grade the overall severity of symptoms on a

10-cm visual analogue scale (VAS), with higher scores indicating more

severe symptoms.

The women maintained a pictorial blood loss

assessment chart (PBAC) for two menstrual cycles. The PBAC is a validated

self-reporting tool with a score calculated every 4 weeks.15 A score ≥100 represents heavy menstrual bleeding, and

≤75 represents normal menses.

The first 60 women filled out the two

questionnaires again 2 weeks later and returned them by mail to

researchers. In addition, a question on perceived change in clinical

condition over the past 2 weeks was asked.

Women were offered appropriate treatment as

clinically indicated. In general, tranexamic acid 500 mg 4 times daily

and/or mefenamic acid 500 mg 3 times daily were prescribed for menorrhagia

unless contra-indicated. Combined oral contraceptive pills were given if

contraception was required and when there was no contraindication. If

medical treatment failed, treatment including endometrial ablation, a

levonorgestrel-containing contraceptive device, myomectomy or

hysterectomy, or uterine artery embolisation (UAE) were offered.

The first half of the recruited women were followed

up 6 months later. They were asked to perform PBAC, and complete blood

work was performed. During follow-up, the women filled out the above

questionnaires again before the gynaecologist’s assessment. The women were

also asked about improvement after treatment.

Sample size and statistical analysis

A sample size of five or more respondents per item

has been proposed for psychometric analysis.16

17 With the UFS-QOL’s total of 37

items and assuming a 20% discard rate due to incomplete filling of

questionnaires, a sample size of 220 was required to adequately assess the

questionnaire.18

We used SPSS (Windows version 20.0; IBM Corp,

Armonk [NY], United States) for statistical analysis. The psychometric

properties of the UFS-QOL were assessed following the American

Psychological Association’s Standards for Educational and Psychological

Testing.19

Reliability

Reliability was assessed by internal consistency

and test-retest correlation. Internal consistency was assessed by

Cronbach’s alpha coefficients, with >0.7 being considered acceptable.16 17

Test-retest reliability was analysed in women who reported no change to

health status over the 2-week period from the first questionnaire.

Test-retest reliability was assessed by intra-class correlation

coefficient. Values between 0.6 and 0.8 indicate substantial agreement,

and values over 0.8 indicate near-perfect agreement.20

Validity

The convergent validity of the UFS-QOL was

estimated by Pearson’s correlation, with participant-rated symptom

severity VAS score, PBAC score, and physician-rated symptom severity VAS

score as well as the quality of life domains of the SF-12. For

discriminant validity, the women were stratified into mild, moderate, and

severe symptoms according to the women-rated symptom severity VAS scores.

A score of VAS ≤4 was classified as mild, while ≥7 was classified as

severe symptomatology. The UFS-QOL scores were compared among the three

groups.

Responsiveness

Responsiveness was evaluated by comparing pre- and

post-treatment scores using paired samples t tests or Wilcoxon

signed rank tests. The effect size (ie, change in mean score divided by

the standard deviation of the baseline)20

and standardised response mean (ie, change in mean score divided by the

standard deviation of the change) were calculated. A value of 0.2 was

considered as a ‘small’ effect, 0.5 a ‘moderate’ effect, and ≥0.8 a

‘large’ effect.

Results

A total of 223 women were recruited. Their mean age

was 44.8±6.0 years (range, 28-62 years). There were multiple fibroids in

54.5% of the participants, and 51.6% of the women had uterine size ≥12

weeks. Overall, 28.3%, 73.3%, 47.1%, and 29.1% reported cycle

irregularity, menorrhagia, dysmenorrhoea, and pressure symptoms from

fibroids, respectively, while 12.1% were asymptomatic. The median UFS-QOL

score at recruitment was 40.6 (interquartile range [IQR]=25.0-56.3) and

67.2 (IQR=48.3-83.6) for symptom severity and HRQL, respectively.

Reliability

The internal consistency and test-retest

reliability values are shown in Table 1. The Cronbach’s alpha values of all

subscales were >0.7. Fifty-one women (85%) returned the questionnaire 2

weeks after the initial visit. All of them reported no health changes.

Test-retest reliability indicated substantial to perfect agreement.

Validity

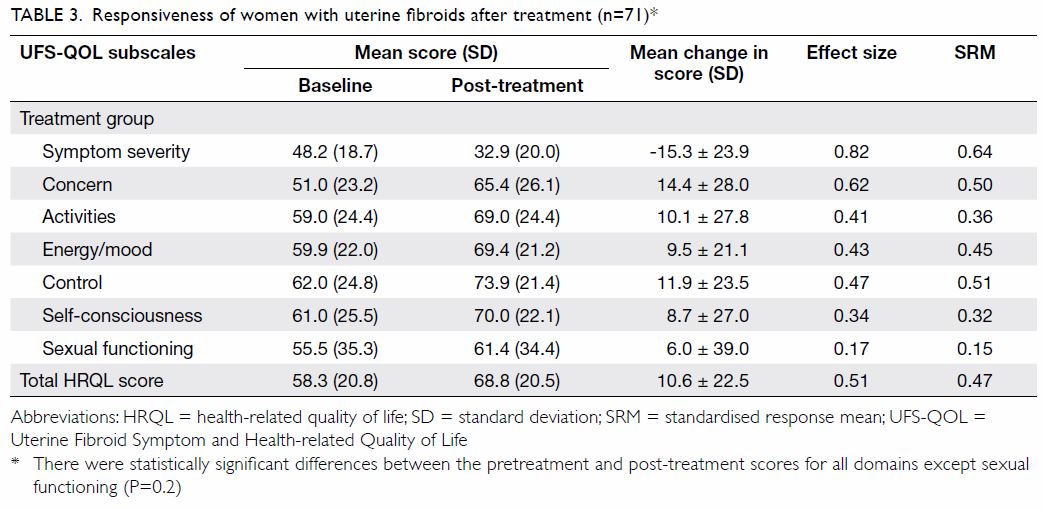

Convergent validity was assessed by the degree of

correlation of the UFS-QOL symptoms severity score on the one hand with

the women-rated and physician-rated VAS scores and PBAC score on the

other. There was a moderate degree of correlation between the UFS-QOL and

these assessment tools (Table 2).

Table 2. Convergent validity—Pearson’s correlation between UFS-QOL symptom severity subscale, VAS by women and gynaecologists, and PBACs

A negative correlation was seen between the UFS-QOL

symptom severity subscale and all domains of the SF-12, and a positive

correlation was observed between the HRQL subscales and SF-12 domains. The

energy/mood and activities subscales had the strongest correlation with

the role-emotional domain of the SF-12 (r=0.597, P<0.001).

The UFS-QOL scores for symptomatic and asymptomatic

women were significantly different across all subscales (median symptom

severity score: 43.8 vs 21.9, P<0.001; median HRQL score: 79.3 vs 63.8,

P<0.001). For women with clinically palpable uterus, the scores on the

control and self-consciousness subscales were lower than those of women

with smaller uterus size (median score of control subscale: 65.0 vs 75.0,

P=0.025; median score of self-consciousness subscale: 67.0 vs 75.0,

P=0.015). Women with significant anaemia (haemoglobin level <80 g/L)

had lower energy and activity subscale scores (median energy score: 50.0

vs 67.9, P=0.014; median activity score: 42.9 vs 66.1, P=0.013) than women

who were not anaemic had.

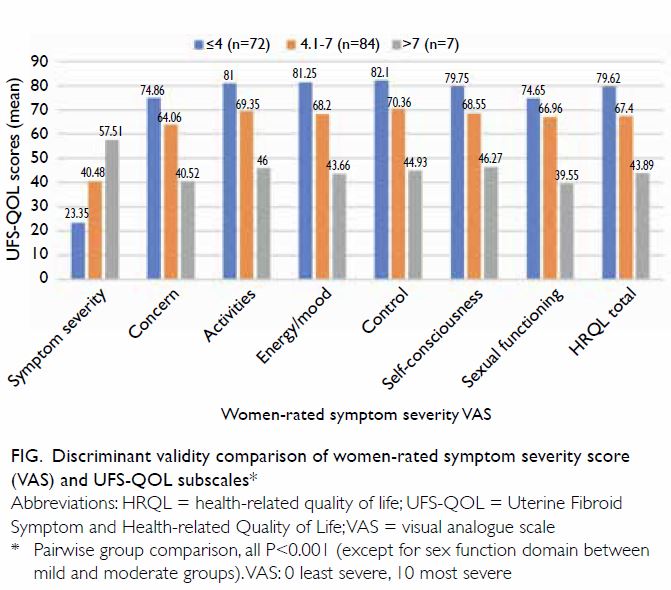

Women were classified into three groups (mild,

moderate and severe symptoms) according to their symptom severity VAS

score (≤4, 4.1-7, and ≥7). Higher women-rated severity score was

associated with higher UFS-QOL symptom severity score, with significant

differences between different severity groups. Similarly, higher women’s

VAS severity score was associated with lower UFS-QOL HRQL scores. The

differences in UFS-QOL score among the three groups were statistically

significant (P<0.001) for all except the mild versus moderate groups on

the sexual functioning subscale (Fig).

Figure. Discriminant validity comparison of women-rated symptom severity score (VAS) and UFS-QOL subscales

Responsiveness

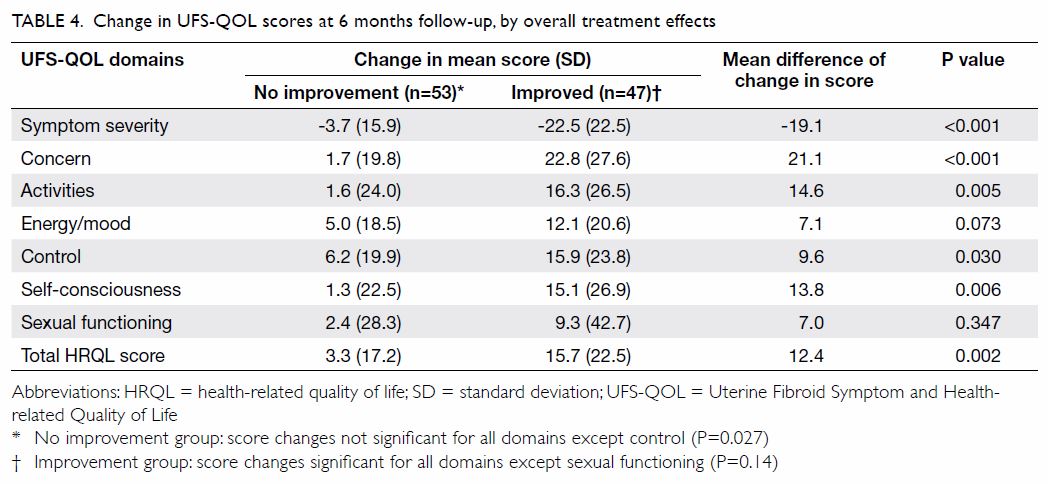

Among the 100 women being followed up, 50 received

medical treatment, 21 received surgery and UAE (15 hysterectomies, 4

myomectomies, 2 UAE), and 29 did not receive any treatment. There was a

significant reduction in symptom severity score and improvement in HRQL

subscale scores after any treatment, except on the sexual functioning

subscale (Table 3). Despite the results being statistically

insignificant, the sexual functioning subscale still showed a trend

towards quality of life improvement with treatment. For surgically treated

women, the reduction in symptom severity score ranged from 22 to 38 with a

large effect size (range, 0.8-2.6).

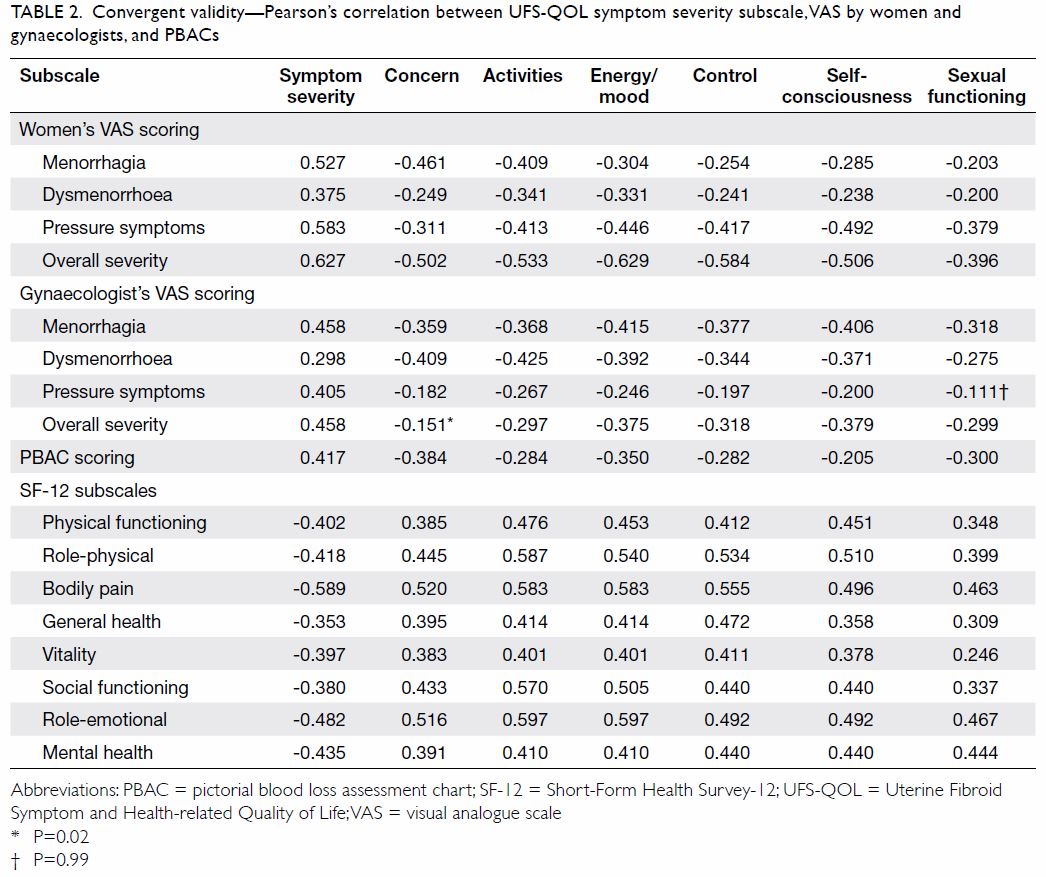

For women reporting no improvement (n=53),

reduction in symptom severity scores and improvement in HRQL scores were

modest except for the control subscale (P=0.027). For those participants

who reported improvement (n=47), there was a significant reduction in

symptom severity score and improvement in HRQL scores. The changes were

significant except for the sexual functioning subscale (P=0.14). Women who

reported improvement demonstrated greater improvement in symptom severity

and all HRQL subscales by 7 to 19 points. The differences were significant

for all except the energy/mood and sexual functioning subscales (Table

4).

Discussion

Fibroids are common in women, and the Chinese

population is no exception. Newer treatments such as ulipristal acetate

and high intensity focused ultrasound ablation can shrink fibroids to

improve symptoms.21 22 23 24 Assessment of effects on quality of life is essential

for evaluation of the usefulness of these modalities.

The UFS-QOL is a simple, disease-specific tool that

has been used in various studies to assess treatment outcomes. The Chinese

version of the UFS-QOL needs to be validated before application for

clinical and research purposes because of cultural differences and

language-specific concerns.

Our results showed that the Chinese UFS-QOL is a

reliable tool with high internal consistency (Cronbach’s alpha >0.7 for

all subscales) and almost perfect agreement between test and retest

results (intra-class correlation coefficient >0.8 for all except the

sexual functioning subscale). These results are comparable with the

original and other translated version of the UFS-QOL.8 13

The validity of the Chinese UFS-QOL was supported

by moderate positive correlations between the women-rated VAS score,

physician-rated VAS score, PBAC score, and UFS-QOL symptom severity score

(with correlation coefficients ranging 0.3-0.6). There was also a moderate

positive correlation between the SF-12 and UFS-QOL HRQL subscale scores.

The energy/mood domain of the UFS-QOL had the strongest correlation with

the SF-12 role-emotion domain (r=0.597). Women with larger uterus

size scored lower in the control and self-consciousness domains, and those

with significant anaemia also had lower energy and activity scores. These

results reflected the ability of the Chinese UFS-QOL to assess the

underlying constructs.

The Chinese UFS-QOL also demonstrated

responsiveness towards change in women who received treatment. The mean

change in subscale scores ranged from 6 to 15 points at 6 months

post-treatment. The changes were most pronounced for women who received

surgery (myomectomy or hysterectomy), who had a mean score increase from

22 to 39 and an effect size of ≥0.8 for all subscales. Similar findings

were also reported in a previous study.23

In addition, larger score changes was observed in women who received

surgery compared with medical treatment, an effect that has also been

shown in other studies.24 The

Chinese UFS-QOL was able to discriminate between women who reported that

their treatment was effective compared with those who did not. Although

there were mean increases of 7 points in both the energy/mood and sexual

functioning subscales, they did not reach statistical significance. This

might be explained by the fact that mood and sexual satisfaction could be

affected by multiple factors other than fibroid symptoms alone.

Improvement in fibroid-related symptoms alone might not result in dramatic

changes in these aspects of quality of life.

Strengths and limitations

Our study sample included a wide range of

disease severities and a broad symptom spectrum, which allows generalisation of the

findings to the community of women with fibroids. Another strength is that

the responsiveness of the UFS-QOL was evaluated, which allows its use to

assess treatment effects. However, the study has a few limitations. The

minimal important difference, ie, the smallest clinically significant

change in score large enough to implicate treatment, was not assessed. In

addition, the majority of women who returned for follow-up received either

medical treatment or hysterectomy, whereas few underwent myomectomy

or UAE. Further studies may be required to address these issues. Finally,

there are two forms of written Chinese characters (traditional and

simplified). Because the Chinese UFS-QOL is a self-administered

questionnaire written in traditional Chinese, application to women who can

read only simplified Chinese characters may be limited.

Conclusion

Our study showed that the Chinese version of

UFS-QOL is comparable to the original and other translated version of this

questionnaire in terms of reliability, validity,8

9 13

and responsiveness.10 In

conclusion, the Chinese version of the UFS-QOL is a reliable, valid tool

for the assessment of symptom severity and HRQL. It can be used to

evaluate efficacy and treatment effects on fibroids in women in the

future.

Author contributions

All authors had full access to the data,

contributed to the study, approved the final version for publication, and

take responsibility for its accuracy and integrity.

Concept or design: SY Yeung, SM Law, SSC Chan.

Acquisition of data: SY Yeung, SM Law, JWK Kwok.

Analysis or interpretation of data: SY Yeung, JWK Kwok.

Drafting of the article: SY Yeung.

Critical revision for important intellectual content: SM Law, SSC Chan, JPW Chung.

Acquisition of data: SY Yeung, SM Law, JWK Kwok.

Analysis or interpretation of data: SY Yeung, JWK Kwok.

Drafting of the article: SY Yeung.

Critical revision for important intellectual content: SM Law, SSC Chan, JPW Chung.

Acknowledgement

The authors thank Dr Linda WY Fung for performing

the forward translation, Dr Alyssa SW Wong for the backward translation,

Professor Sonia Grover and Dr Sotirios Saravelos for evaluating the final

English version against the original questionnaire.

Conflicts of interest

As an editor of the journal, JPW Chung was not

involved in the peer review process of the article. Other authors have

disclosed no conflict of interest.

Declaration

The preliminary results of part of this study

(reliability and validity) have been presented during an oral presentation

session at the 25th Asian & Oceanic Congress of Obstetrics &

Gynaecology in Hong Kong, June 2017.

Funding/support

This research received no specific grant from any

funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Ethics approval

Ethics approval was obtained in April 2015 from the

Joint Chinese University of Hong Kong–New Territories East Cluster

Clinical Research Ethics Committee (CREC Ref 2015.085).

References

1. Stewart EA, Cookson CL, Gandolfo RA,

Schulze-Rath R. Epidemiology of uterine fibroids: a systematic review.

BJOG 2017;124:1501-12. Crossref

2. Okolo S. Incidence, aetiology and

epidemiology of uterine fibroids. Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol

2008;22:571- 88. Crossref

3. Vercellini P, Vendola N, Ragni G,

Trespidi L, Oldani S, Crosignani PG. Abnormal uterine bleeding associated

with iron-deficiency anemia. Etiology and role of hysteroscopy. J Reprod

Med 1993;38:502-4.

4. Emanuel MH, Verdel MJ, Stas H, Wamsteker

K, Lammes FB. An audit of true prevalence of intra-uterine pathology: the

hysteroscopical findings controlled for patient selection in 1202 patients

with abnormal uterine bleeding. Gynaecological Endoscopy 1995;4:237-42.

5. Ando K, Morita S, Higashi T, et al.

Health-related quality of life among Japanese women with iron-deficiency

anemia. Qual Life Res 2006;15:1559-63. Crossref

6. Dancz CE, Kadam P, Li C, Nagata K, Özel

B. The relationship between uterine leiomyomata and pelvic floor symptoms.

Int Urogynecol J 2014;25:241-8. Crossref

7. Moshesh M, Olshan AF, Saldana T, Baird

D. Examining the relationship between uterine fibroids and dyspareunia

among premenopausal women in the United States. J Sex Med 2014;11:800-8. Crossref

8. Spies JB, Coyne K, Guaou Guaou N, Boyle

D, Skyrnarz-Murphy K, Gonzalves SM. The UFS-QOL, a new disease-specific

symptom and health-related quality of life questionnaire for leiomyomata.

Obstet Gynecol 2002;99:290-300. Crossref

9. Coyne KS, Margolis MK, Bradley LD, Guido

R, Maxwell GL, Spies JB. Further validation of the uterine fibroid symptom

and quality-of-life questionnaire. Value Health 2012;15:135-42. Crossref

10. Harding G, Coyne KS, Thompson CL,

Spies JB. The responsiveness of the uterine fibroid symptom and

health-related quality of life questionnaire (UFS-QOL). Health Qual Life

Outcomes 2008;6:99. Crossref

11. Smith WJ, Upton E, Shuster EJ, Klein

AJ, Schwartz ML. Patient satisfaction and disease specific quality of life

after uterine artery embolization. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2004;190:1697-703.

Crossref

12. Olive DL. Sustained relief of

leiomyoma symptoms by using focused ultrasound surgery. Obstet Gynecol

2008;111:775. Crossref

13. Oliveira Brito LG, Malzone-Lott DA,

Sandoval Fagundes MF, et al. Translation and validation of the Uterine

Fibroid Symptom and Quality of Life (UFS-QOL) questionnaire for the

Brazilian Portuguese language. Sao Paulo Med J 2017;135:107-15. Crossref

14. Lam CL, Tse EY, Gandek B. Is the

standard SF-12 health survey valid and equivalent for a Chinese

population? Qual Life Res 2005;14:539-47. Crossref

15. Higham JM, O’Brien PM, Shaw RW.

Assessment of menstrual blood loss using a pictorial chart. Br J Obstet

Gynaecol 1990;97:734-9. Crossref

16. Bryant FB, Yarnold PR. Principal

components analysis and exploratory and confirmatory factor analysis. In:

Grimm LG, Yarnold PR, editors. Reading and Understanding Multivariate

Statistics. American Psychological Association, Washington DC; 1995:

99-136.

17. Gorsuch RL. Factor Analysis. 2nd ed.

Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; 1983.

18. Machin D, Campbell MJ, Tan SB, Tan SH.

Sample Size Tables for Clinical Studies, 3rd ed. Chichester, UK:

Wiley-Blackwell; 2009. Crossref

19. American Educational Research

Association, American Psychological Association, National Council on

Measurement in Education; Joint Committee on Standards for Educational and

Psychological Testing. Standards for educational and psychological

testing. Washington, DC: American Educational Research Association; 1999.

20. Cohen J. Statistical power analysis

for the behavioral sciences. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates;

1988.

21. Donnez J, Hudecek R, Donnez O, et al.

Efficacy and safety of repeated use of ulipristal acetate in uterine

fibroids. Fertil Steril 2015;103:519-27.e3. Crossref

22. Donnez J, Donnez O, Matule D, et al.

Long-term medical management of uterine fibroids with ulipristal acetate.

Fertil Steril 2016;105:165-73.e4. Crossref

23. Froeling V, Meckelburg K, Schreiter

NF, et al. Outcome of uterine artery embolization versus MR-guided

highintensity focused ultrasound treatment for uterine fibroids: long-term

results. Eur J Radiol 2013;82:2265-9. Crossref

24. Chan SS, Cheung RY, Lai BP, Lee LL,

Choy KW, Chung TK. Responsiveness of the Pelvic Floor Distress Inventory

and Pelvic Floor Impact Questionnaire in women undergoing treatment for

pelvic floor disorders. Int Urogynecol J 2013;24:213-21. Crossref