Hong Kong Med J 2019 Dec;25(6):444–52 | Epub 4 Dec 2019

© Hong Kong Academy of Medicine. CC BY-NC-ND 4.0

ORIGINAL ARTICLE

Natural clinical course of progressive supranuclear

palsy in Chinese patients in Hong Kong

YF Shea, FHKAM (Medicine), FHKCP1; Alex

CK Shum, FHKAM (Medicine), FHKCP2; SC Lee, BHS (Nursing)1;

Patrick KC Chiu, FHKAM (Medicine), FHKCP1; KS Leung, FHKAM

(Medicine), FHKCP2; YK Kwan, FHKAM (Medicine), FHKCP2;

Francis CK Mok, FHKAM (Medicine), FHKCP2; Felix HW Chan, FHKAM

(Medicine), FHKCP2

1 Department of Medicine, Queen Mary

Hospital, Pokfulam, Hong Kong

2 Department of Medicine and Geriatrics,

Tuen Mun Hospital, Tuen Mun, Hong Kong

Corresponding author: Dr YF Shea (elphashea@gmail.com)

Abstract

Introduction: Progressive

supranuclear palsy (PSP) is a common type of atypical parkinsonism. To

the best of our knowledge, there has been no study of its natural

clinical course among Chinese patients.

Methods: This retrospective

study included 21 patients with PSP who had radiological evidence of

midbrain atrophy (confirmed by magnetic resonance imaging) from the

geriatrics clinics of Queen Mary Hospital and Tuen Mun Hospital.

Clinical information was retrieved from clinical records, including age

at onset, age at presentation, age at death, duration of symptoms, level

of education, sex, presenting scores on Cantonese version of Mini-Mental

State Examination, clinical symptoms, and history of levodopa or

dopamine agonist intake and response. Clinical symptoms were clustered

into the following categories and the dates of development of these

symptoms were determined: motor symptoms, bulbar symptoms, cognitive

symptoms, and others.

Results: Motor symptoms

developed early in the clinical course of disease. Cox proportional

hazards modelling showed that the number of episodes of pneumonia, time

to vertical gaze palsy, and presence of pneumonia were predictive of

mortality. Apathy, dysphagia, pneumonia, caregiver stress, and pressure

injuries were predictive of mortality when analysed as time-dependent

covariates. There was a significant negative correlation between the age

at presentation and time to mortality from presentation (Pearson

correlation=-0.54, P=0.04). Approximately 40% of caregivers complained

of stress during the clinical course of disease.

Conclusion: Important clinical

milestones, including the development of dysphagia, vertical gaze palsy,

significant caregiver stress, pressure injuries, and pneumonia, may

guide advanced care planning for patients with PSP.

New knowledge added by this study

- Although this was a small cohort, 57% of patients with progressive supranuclear palsy (PSP) were initially misdiagnosed.

- Important clinical milestones, including the development of apathy, dysphagia, vertical gaze palsy, significant caregiver stress, pressure injuries, and pneumonia, were predictive of mortality in patients with PSP.

- Monitoring of vertical gaze palsy or levodopa response is important throughout the clinical course of disease in patients with PSP.

- Important clinical milestones, including the development of dysphagia, vertical gaze palsy, significant caregiver stress, pressure injuries and pneumonia, may be used to guide the ideal timing for discussions of advanced care planning for patients with PSP.

Introduction

With the ageing of the Hong Kong population,

clinicians must monitor increasing numbers of patients with

neurodegenerative disease. Progressive supranuclear palsy (PSP) is a

common form of atypical parkinsonism,1

with a prevalence of up to 18 cases per 100 000 people.1 Pathologically, PSP is characterised by the presence of

neurofibrillary tangles, neuropil threads, or both in the basal ganglia

and brainstem.1 In patients with

classical Richardson’s syndrome, the disease is characterised by early

postural instability, falls, vertical gaze palsy, parkinsonism with poor

response to levodopa, pseudobulbar palsy, and frontal release signs.2 Increasingly, patients with PSP have been reported to

exhibit the following manifestations: parkinsonism, progressive gait

freezing, corticobasal syndrome, apraxia of speech, frontal presentation,

or cerebellar ataxia.2 Despite

advancements in understanding the disease, there remains no approved

treatment for PSP.

In addition to the need for accurate diagnosis of

PSP, the natural clinical course of the disease is a concern for

caregivers.3 4 Important problems for patients with PSP include

increased risks of falls, dysphagia, aspiration pneumonia, pressure

injuries, caregiver stress leading to institutionalisation, and long-term

mortality.1 Given the lack of

definitive treatment, it remains prudent for clinicians to educate

caregivers regarding the natural course of PSP, which will ensure that

caregivers are better prepared to care for their relatives; it will also

allow implementation of different methods to avoid long-term

complications, and may facilitate discussions of advanced care planning

(ACP) at earlier stages of disease.3

In particular, clinicians need to identify the appropriate timing to

discuss ACP. Previous studies have shown that the mean age at onset of PSP

is 61 to 67.2 years, and that the disease affects both sexes equally;

moreover, the median survival ranges from 5.3 to 10.2 years.5 Factors predictive of mortality included age at onset,

early clinical milestones (eg, falls, vertical gaze palsy, neck or limb

stiffness, dysphagia, and incontinence), cognitive impairment, language

impairment, autonomic dysfunction, male sex, and certain subtypes of PSP,

such as classical Richardson’s syndrome and pneumonia.6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16

To the best of our knowledge, there have been no

studies of the natural clinical course of disease in Chinese patients with

PSP. This information is important for clinical treatment and the design

of future intervention studies (eg, for the purposes of sample size

estimation). In the present study, we hypothesised that bulbar symptoms

and pneumonia could predict mortality in patients with PSP. The aims of

this study were (1) to calculate the prevalences of motor symptoms,

cognitive symptoms, bulbar symptoms, other systemic symptoms, and

long-term outcomes (eg, falls, tube feeding, pressure injuries, and

institutionalisation) during the clinical course of PSP, and (2) to

identify factors predictive of mortality among patients with PSP.

Methods

Patients

This retrospective study protocol was approved by

the Institutional Review Board of the University of Hong Kong/Hospital

Authority Hong Kong West Cluster (HKU/HA HKW IRB; Approval No. UW 17-483)

and New Territories West Cluster Clinical and Research Ethics Committee

(NTWC CREC; Approval No. NTWC/CREC/17127); the requirement for informed

consent was waived by the review board. This study comprised a

retrospective review of the clinical records of all patients who presented

to the geriatrics clinics of Queen Mary Hospital and Tuen Mun Hospital

between 1 January 2008 and 30 December 2017. All patients had at least 1

year of clinical follow-up and fulfilled the latest Movement Disorder

Society Criteria for clinical diagnosis of PSP.2

In addition, magnetic resonance imaging scans showed radiological evidence

of midbrain atrophy (Hummingbird sign or Morning Glory sign) in all

patients, according to radiological reports prepared by licensed

radiologists.1 Twenty-five patients

with clinically probable PSP and radiological evidence of midbrain atrophy

were considered for inclusion in this study. Four patients were excluded

because their clinical history and radiology findings were not suggestive

of PSP. Finally, 21 patients were included: 19 had Richardson syndrome

variant, one had PSP-corticobasal syndrome, and one had PSP with language

impairment. The patient who had PSP with language impairment was

previously described.17 Seven and

14 patients were recruited from Queen Mary Hospital and Tuen Mun Hospital,

respectively.

Baseline clinical information retrieved

Clinical information was retrospectively retrieved

from clinical records, including age at onset, age at presentation, age at

death, duration of symptoms, level of education, sex, presenting scores on

Cantonese version of Mini-Mental State Examination (C-MMSE),18 clinical symptoms, and history of levodopa or

dopamine agonists intake or response. Clinical symptoms were clustered

into the following categories: motor symptoms (including limb or neck

stiffness, slowness of movement, balance impairment, gait impairment,

falls, tremor, and vertical gaze palsy), bulbar symptoms (including

dysarthria, dysphagia, and drooling), cognitive symptoms (including memory

impairment, apathy, apraxia, dysexecutive syndrome, behavioural

disinhibition, repetitive motor behaviour, hyperorality, and visual

hallucination), and others (including faecal or urinary incontinence,

constipation, insomnia, depression, and caregiver stress).6 The dates of development of the above symptom clusters

were retrospectively determined.

‘Age at presentation’ was defined as the age at

which the patient first presented to the geriatrics clinic. ‘Duration of

symptoms’ was defined as the time between the first appearance of clinical

symptoms of neurodegenerative disease and the first presentation. ‘Age at

onset’ was defined as the difference between the ‘age at presentation’ and

the ‘duration of symptoms’. ‘Disease duration’ was defined as the

difference between ‘age at onset’ and ‘age at death’ or the last date of

follow-up. ‘Time to diagnosis’ was defined as the time between the date of

disease onset and the date of diagnosis with PSP. The times to development

of the above categories of symptoms were calculated in relation to both

disease onset and presentation.

Long-term outcomes

Long-term outcomes were recorded, including falls,

dysphagia, pneumonia, pressure sore development, and mortality. ‘Time to

event’ was defined by the difference between the onset of clinical

symptoms and first appearance of these long-term events. The time to each

event from the time of first presentation was also calculated.

Falls

These were defined as events that resulted in the

patient’s body or body part inadvertently coming to rest on the ground or

other surface lower than the body. The dates and numbers of falls were

recorded. Geriatric day hospital training was recorded, including the

pre-/post-training elderly mobility scale.19

Parkinsonism medications were often titrated in the geriatric day

hospital.

Pneumonia

A diagnosis of pneumonia was made based on the

following criteria: clinical signs and symptoms, white cell count of

≥10×109/L or proportion of neutrophils of ≥80%, fever (body

temperature of ≥37.6℃), and new infiltrates or consolidations on chest

radiography (X-ray or computed tomography).20

The dates and total numbers of pneumonia diagnoses were recorded.

Dysphagia

Any documentation of dysphagia by a speech

therapist was recorded; alternatively (if available), reports of video

fluoroscopic swallowing studies were obtained. Penetration was defined as

the entry of barium material into the airway without passage below the

vocal cords; aspiration was defined as the passage of barium material

below the level of the vocal cords.21

The dates of diagnosis of dysphagia and tube feeding were recorded.

Pressure injuries

The locations of pressure injuries and their

stages, according to National Pressure Ulcer Advisory Panel guidelines,

were recorded.22 The dates of

discovery of pressure injuries were recorded.

Institutionalisation

This was defined as institutionalisation of the

patient, regardless of the level of care (eg, personal care facility or

health care facility). The dates of institutionalisation were recorded

where possible.

Mortality

The date and cause of death were recorded.

Statistical analysis

For descriptive statistics, continuous variables

with normal distributions were expressed as means ± standard deviations;

variables that did not exhibit a normal distribution were expressed as

medians (interquartile ranges). Symptom prevalences (cumulative

incidences) were estimated using Kaplan-Meier method, with the first

presentation defined as time zero. Patients who did not exhibit a

particular symptom by the most recent assessment were censored at that

point. Median times to clinical events were used as cut-offs to define

‘early’ or ‘late’ development of those events (binary classification).

Time zero was consistently defined as the first clinical presentation or

onset of disease, while the event time was defined as the number of months

from first presentation or disease onset to occurrence of the event. Cox

proportional hazards modelling was used to identify factors predictive of

mortality based on the above binary classification or clinical events as

time-dependent covariates. Pearson correlation coefficients were used to

study the correlations between age at presentation and time to mortality

(from the date of presentation). A two-tailed P value of <0.05 was

considered statistically significant. All statistical analyses were

performed using SPSS for Windows (version 24; IBM Corp, Armonk [NY],

United States).

Results

Basic demographics

Twenty-one patients were included in this analysis,

with a total of 1671.4 months of follow-up from onset (1428.4 months from

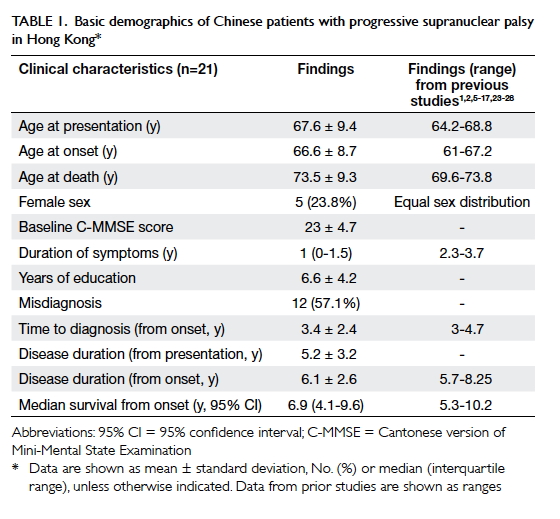

presentation). The baseline demographics are summarised in Table

1. The mean age of the patients at presentation was 67.6 ± 9.4

years, and most patients were men (76.2%). Fifty-seven percent of the

patients received another diagnosis at the time of presentation: nine

patients were diagnosed with Parkinson’s disease, one patient was

diagnosed with Lewy body dementia, one patient was diagnosed with cervical

myelopathy, and one patient was diagnosed with myasthenia gravis. None of

the patients showed improvement when treated with levodopa or a dopamine

agonist. Six patients (28.6%) exhibited dementia at the time of

presentation. Seventeen patients (81%) had been referred to the geriatric

day hospital for rehabilitation after a median of 20 months from

presentation; they showed improvement in elderly mobility scale score

(pre-geriatric day hospital elderly mobility scale score vs post-geriatric

day hospital elderly mobility scale score: 14 ± 4.6 vs 16 ± 4.3,

respectively, P=0.02). Fifteen patients (71.4%) died during follow-up with

mean survival of 6.1 ± 2.6 years from onset (5.2 ± 3.2 years from

presentation); 12 of these 15 patients (80%) died of pneumonia, while two

(13.3%) died of sudden cardiac arrest.

Clinical features

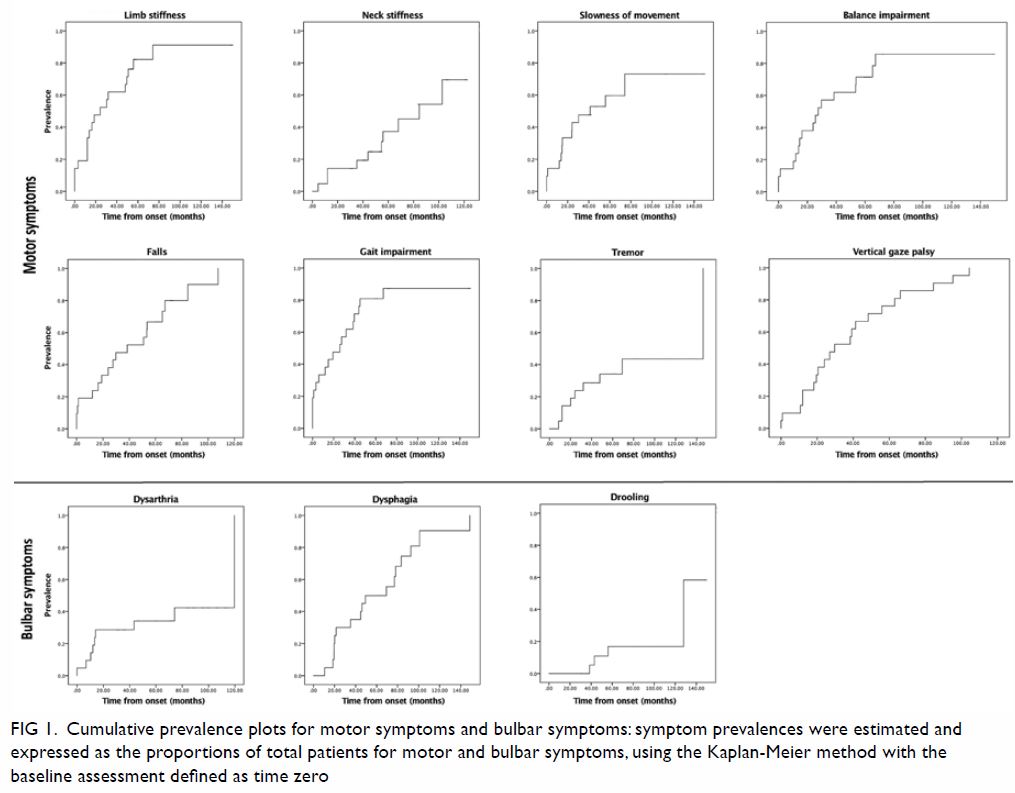

Among the categories of potential symptoms, motor

symptoms were most prevalent during initial presentation (specific

symptoms affected up to 33.3% of patients) [Fig 1]. Motor manifestations were among the earliest

clinical features observed in patients with PSP (online supplementary Appendix). The most frequent

motor symptoms at the time of presentation were limb stiffness (33.3%) and

gait impairment (28.6%). Vertical gaze palsy was present in 19% of

patients at the time of presentation, but eventually affected all patients

(100%). The prevalence of gait impairment increased rapidly, such that

≥80% of the patients were affected within 3 years after presentation. All

motor features showed increased in prevalence over time, with final

prevalences ranging from 47.6% to 100%. Regarding bulbar symptoms,

dysarthria was the most frequent presenting symptom (9.5%). Both

dysarthria and dysphagia reached 100% prevalence over time (Fig

1).

Figure 1. Cumulative prevalence plots for motor symptoms and bulbar symptoms: symptom prevalences were estimated and expressed as the proportions of total patients for motor and bulbar symptoms, using the Kaplan-Meier method with the baseline assessment defined as time zero

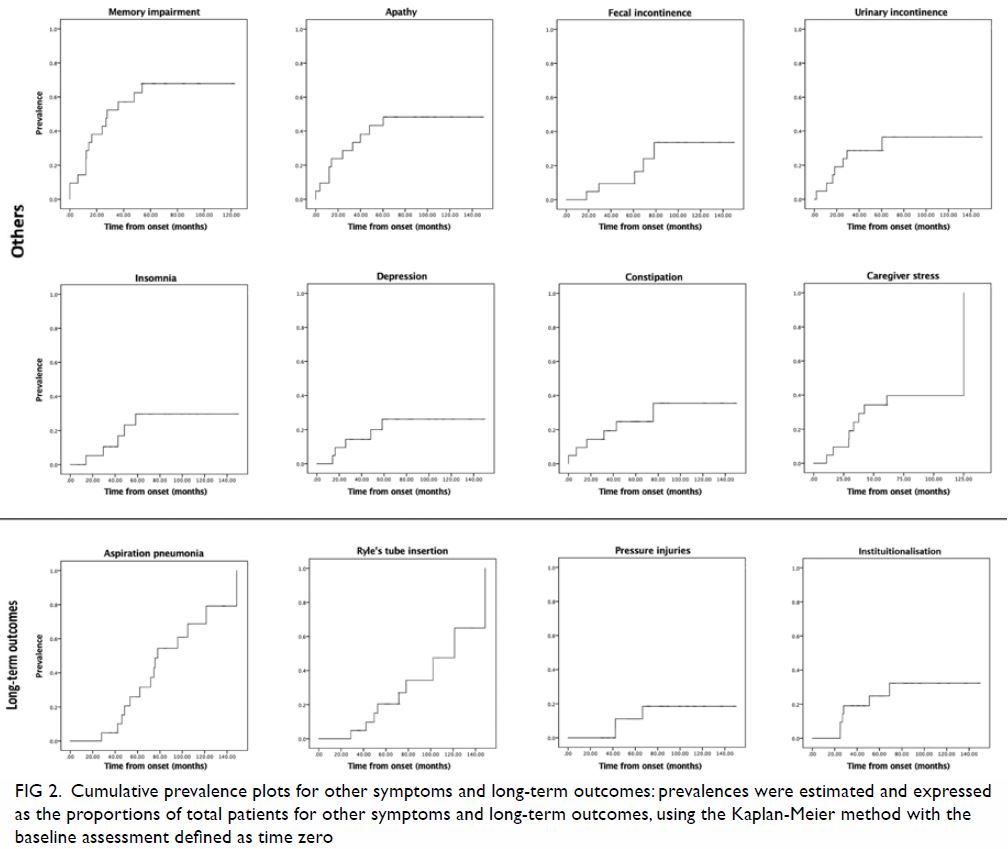

Regarding cognitive symptoms, memory impairment and

apathy were the two most frequent presenting symptoms, with prevalences of

33.3% and 23.8%, respectively (Fig 2). The respective prevalences of memory

impairment and apathy increased to >65% and >45% over time. The

prevalence of dysexecutive syndrome reached 28.6% during the clinical

course of disease. Other cognitive symptoms relevant to patients with PSP

showed lower prevalence, including apraxia, behavioural disinhibition,

repetitive motor behaviour, hyperorality, and visual hallucination; the

highest prevalence for any of these symptoms was 9.5% throughout the

clinical course of disease. The degree of caregiver stress also increased

with progression of disease, such that it reached approximately 40% within

5 years after initial presentation.

Figure 2. Cumulative prevalence plots for other symptoms and long-term outcomes: prevalences were estimated and expressed as the proportions of total patients for other symptoms and long-term outcomes, using the Kaplan-Meier method with the baseline assessment defined as time zero

Regarding systemic symptoms, faecal and urinary

incontinence showed the highest prevalences (both reached approximately

40%), particularly in the later stages of disease (Fig 2). Regarding long-term outcomes, the

prevalences of aspiration pneumonia and dysphagia requiring Ryle’s tube

insertion both reached 100% over time (Fig 2).

Factors predicting mortality

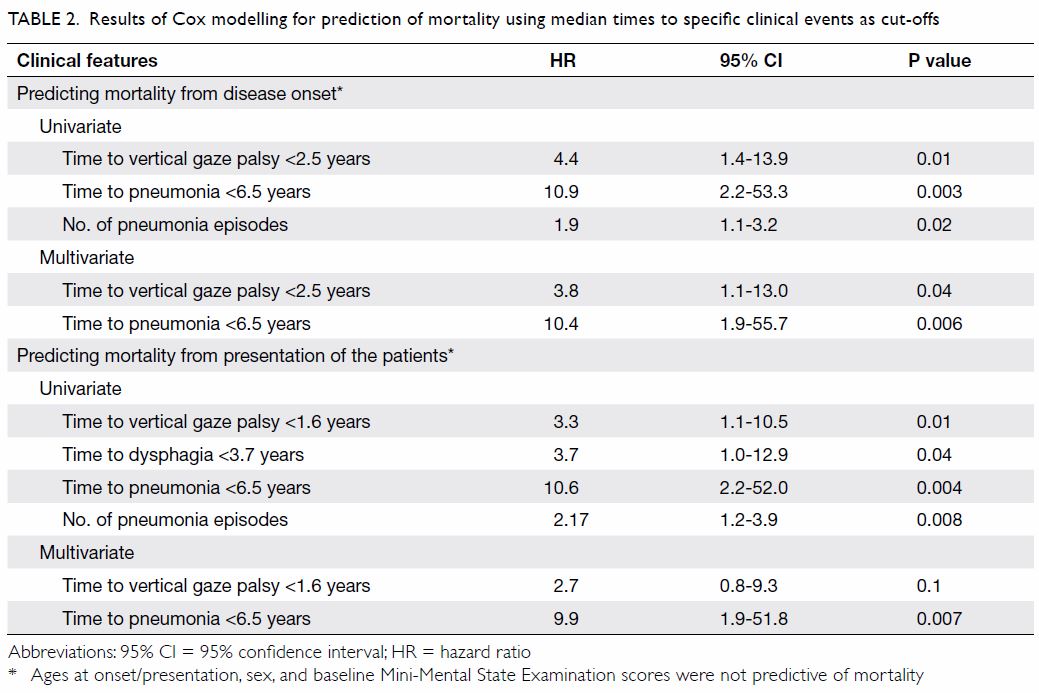

Using median time to clinical events as cut-off

(binary classification) [online supplementary Appendix] and with analysis in

a Cox proportional hazards model, our results showed that earlier

development of vertical gaze palsy (hazard ratio [HR]=4.4, 95% confidence

interval [CI]=1.4-13.9, P=0.01) and earlier development of pneumonia

(HR=10.9, 95% CI=2.2-53.3, P=0.003) were predictive of mortality from

disease onset (Table 2). Multivariate analysis showed that earlier

development of vertical gaze palsy (HR=3.8, 95% CI=1.1-13.0, P=0.04) and

earlier development of pneumonia (HR=10.4, 95% CI=1.9-55.7, P=0.006) were

predictive of mortality from disease onset (Table 2). Earlier development of vertical gaze palsy

(HR=3.3, 95% CI=1.1-10.5, P=0.01), earlier development of dysphagia

(HR=3.7, 95% CI=1.0-12.9, P=0.04), and earlier development of pneumonia

(HR=10.6, 95% CI=2.2-52.0, P=0.004) were predictive of mortality from

disease presentation (Table 2). Multivariate analysis showed that only

earlier development of pneumonia (HR=9.9, 95% CI=1.9-51.8, P=0.007) was

predictive of mortality from presentation (Table 2). The number of episodes of pneumonia was

also predictive of mortality in patients with PSP, indicating that

pneumonia is a major cause of mortality (Table 2). There was a significant negative

correlation between the age at presentation and time to mortality from

presentation (Pearson correlation=-0.54, P=0.04).

Table 2. Results of Cox modelling for prediction of mortality using median times to specific clinical events as cut-offs

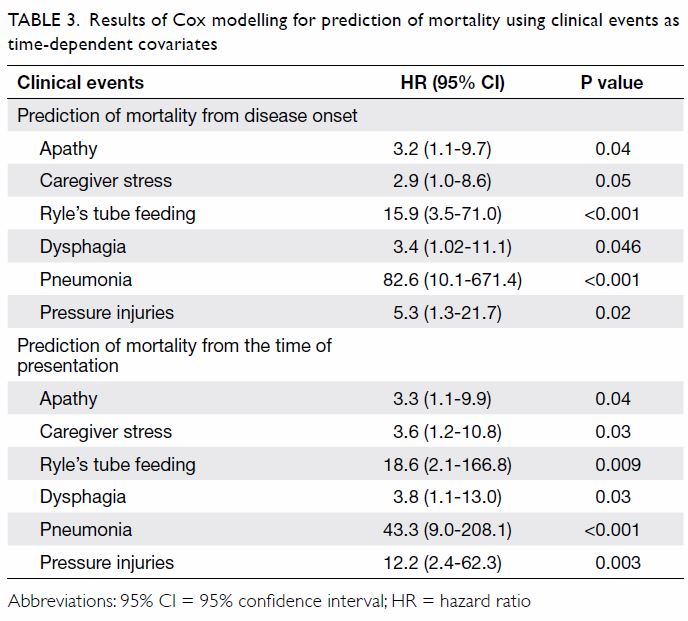

Using clinical events as time-dependent covariates

in Cox modelling for prediction of mortality, we found that apathy,

dysphagia, Ryle’s tube feeding, pneumonia, and pressure injuries were

predictive of mortality from both disease onset and presentation (Table

3). Caregiver stress was only predictive of mortality from

presentation (Table 3).

Table 3. Results of Cox modelling for prediction of mortality using clinical events as time-dependent covariates

Discussion

An accurate diagnosis of PSP is important for

management of the disease in affected patients. However, only 43% of the

patients in this study received a correct diagnosis at the time of initial

presentation. This is potentially because vertical gaze palsy was not

present initially and only developed during clinical follow-up (median

time to develop, 19.6 months; online supplementary Appendix). In addition, 43% of

patients were initially misdiagnosed with Parkinson’s disease; this group

of patients may have had PSP with parkinsonism.2

Clinicians should regularly assess patients with parkinsonism for the

presence of any vertical gaze palsy or poor response to levodopa, in order

to correctly identify patients with PSP. Our reported mean time to

diagnosis of 3 years was similar to the duration reported in previous

studies (mean, 3.1-4 years).1 2 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 23 24 25 26 27 28

With regard to clinical features, our cohort of

patients exhibited early development of motor symptoms, which was

consistent with previous studies.1

2 5

6 7

8 9

10 11

12 13

14 15

16 17

23 24

25 26

27 28

Our cohort of patients showed evidence of improved mobility, as reflected

by changes in elderly mobility scale score after training in the geriatric

day hospital, with a median time to referral of 20 months from the initial

clinical presentation. Patients with PSP should be referred to a

physiotherapist and an occupational therapist for fall assessment, as well

as guidance regarding the potential need for walking aids. Relatives

should be educated to ensure close monitoring of environmental risks for

falls. The patients in our cohort showed relatively early development of

memory problems at a median duration of 9 months, which contrasted with

the mean duration of 12 months observed in another study.6 There may have

been bias in the current cohort, which recruited patients with PSP from a

geriatrics clinic whereas the patients in the previous study were

recruited from a neurology clinic.6

A previous meta-analysis showed mixed results with

regard to whether the age at onset of PSP was predictive of mortality.5 Pooled results from six studies showed no prognostic

effect of yearly increases in age at disease onset in either univariate or

multivariate analyses.5 However,

pooled results from nine studies using median age at onset as cut-off

showed a pooled HR of 1.75 (95% CI=1.32-2.32) in multivariate analysis.5 Other predictors of mortality

found in the present study, including vertical gaze palsy, dysphagia,

pneumonia, or pressure injuries, were previously reported in other

studies.6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 It

remains unknown whether resolution of dysphagia in patients with PSP can

prevent pneumonia and reduce mortality. It is important for clinicians to

refer patients with PSP involving dysphagia to a speech therapist for

advice regarding food texture and appropriate swallowing posture (ie,

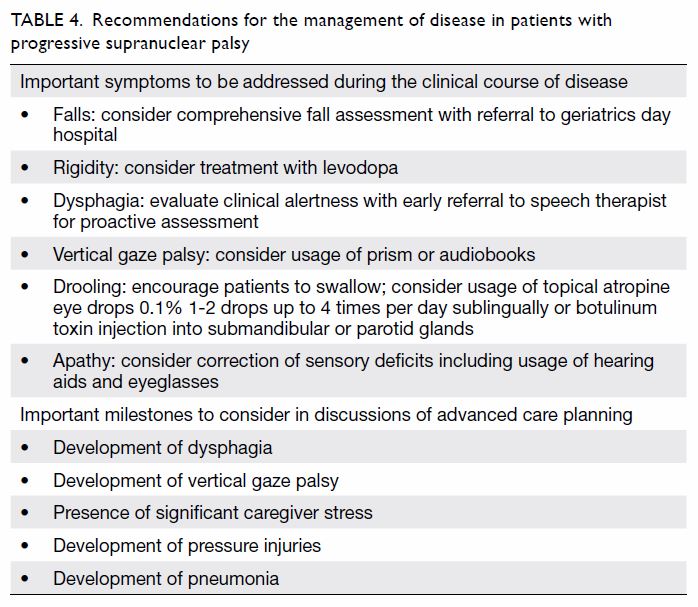

chin-tuck) [Table 4].29

During the clinical course of disease, approximately 40% of primary

caregivers complained of caregiver stress, which was also determined to be

a significant predictor of mortality. Patient aggression and depression

have been reported as sources of stress.4

When these positive predictors of mortality appear, clinicians should

consider discussing ACP with patients or caregivers (Table

4).

Table 4. Recommendations for the management of disease in patients with progressive supranuclear palsy

The finding of apathy as a time-dependent covariate

for prediction of mortality is notable. Recently, apathy was found to

predict survival in a cohort of 124 patients with syndromes associated

with frontotemporal lobar degeneration (including 35 patients with PSP,

mean age of 72.2 ± 8.5 years).30

The development of apathy in patients with PSP was related to brainstem,

midbrain, and frontal atrophy.30

It remains unknown whether apathy accelerates the decline to death or

indirectly signifies the degree of brainstem degeneration, including the

development of dysphagia, which is also related to greater mortality.

Future clinical trials may consider the use of therapeutic measures to

address apathy, in order to assess their impacts on the survival of

patients with PSP.

Because there is currently no disease-modifying

treatment for patients with PSP, ACP is an important component of clinical

care, for which patients and their caregivers can reach a consensus during

the clinical course of disease.4 In

addition, symptomatic care plays an important role. Symptoms relevant to

patients with PSP include dystonia, drooling, gaze palsy (also known as

reduced blinking), constipation, and apathy.4

Drooling could be managed by the administration of sublingual atropine

drops (Table 4).4

Reduced blinking could be managed by frequent application of lubricating

eyedrops. Gaze palsy could be managed by the use of prisms or audiobooks (Table 4).4

Apathy could be minimised by addressing sensory deficits, such as through

the use of eyeglasses or hearing aids (Table 4).4 Up

to 75% of patients with PSP could be discharged home after stabilisation

of symptoms.4

There are multiple limitations in the current

study. First, it was a retrospective study involving reviews of clinical

charts, and may be biased due to inconsistent documentation of symptoms.

Second, there was a limited number of patients included, none of whom had

autopsy and pathological confirmation of their diagnosis; however, we had

radiological evidence of PSP. Third, our descriptive statistical results

should be regarded as preliminary findings; only limited variables could

be included in our Cox proportional hazards modelling for survival

analysis. Notably, no specific scales were used to assess the severity of

parkinsonism or other symptoms, including response to levodopa; most of

our evaluations were subjective. Sequential C-MMSE scores were not

recorded; thus, we were unable to examine the development of dementia over

time. Fourth, we only included patients attending the geriatrics clinic;

therefore, our cohort may not be fully representative of patients with PSP

who present to most neurology clinics. Finally, the limited numbers of

patients precluded stratified analyses based on subtypes of PSP.

In conclusion, important clinical milestones,

including the development of dysphagia, vertical gaze palsy, significant

caregiver stress, pressure injuries, and pneumonia, may be used to guide

the ideal timing for discussions of ACP for patients with PSP, in order to

facilitate long-term care.

Author contributions

All authors had full access to the data,

contributed to the study, approved the final version for publication, and

take responsibility for its accuracy and integrity.

Concept or design: YF Shea, ACK Shum.

Acquisition of data: YF Shea, ACK Shum.

Analysis or interpretation of data: All authors.

Drafting of the article: YF Shea, ACK Shum.

Critical revision for important intellectual content: All authors.

Acquisition of data: YF Shea, ACK Shum.

Analysis or interpretation of data: All authors.

Drafting of the article: YF Shea, ACK Shum.

Critical revision for important intellectual content: All authors.

Conflicts of interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest to

disclose.

Funding/support

This research received no specific grant from any

funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Ethics approval

This retrospective study protocol was approved by

the Institutional Review Board of the University of Hong Kong/ Hospital

Authority Hong Kong West Cluster (HKU/HA HKW IRB; Ref UW 17-483) and New

Territories West Cluster Clinical and Research Ethics Committee (NTWC

CREC; Ref NTWC/CREC/17127). The requirement for informed consent was

waived by the review board.

References

1. Boxer AL, Yu JT, Golbe LI, Litvan I,

Lang AE, Höglinger GU. Advances in progressive supranuclear palsy: new

diagnostic criteria, biomarkers, and therapeutic approaches. Lancet Neurol

2017;16:552-63. Crossref

2. Höglinger GU, Respondek G, Stamelou M,

et al. Clinical diagnosis of progressive supranuclear palsy: The movement

disorder society criteria. Mov Disord 2017;32:853-64. Crossref

3. Luk JK, Chan FH. End-of-life care for

advanced dementia patients in residential care home—a Hong Kong

perspective. Ann Palliat Med 2018;7:359-64. Crossref

4. Wiblin L, Lee M, Burn D. Palliative care

and its emerging role in multiple system atrophy and progressive

supranuclear palsy. Parkinsonism Relat Disord 2017;34:7-14. Crossref

5. Glasmacher SA, Leigh PN, Saha RA.

Predictors of survival in progressive supranuclear palsy and multiple

system atrophy: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Neurol Neurosurg

Psychiatry 2017;88:402-11. Crossref

6. Arena JE, Weigand SD, Whitwell JL, et

al. Progressive supranuclear palsy: progression and survival. J Neurol

2016;263:380-9. Crossref

7. Golbe LI, Davis PH, Schoenberg BS,

Duvoisin RC. Prevalence and natural history of progressive supranuclear

palsy. Neurology 1988;38:1031-4. Crossref

8. Nath U, Ben-Shlomo Y, Thomson RG, Lees

AJ, Burn DJ. Clinical features and natural history of progressive

supranuclear palsy: a clinical cohort study. Neurology 2003;60:910-6. Crossref

9. Oliveira MC, Ling H, Lees AJ, Holton JL,

De Pablo-Fernandez E, Warner TT. Association of autonomic symptoms with

disease progression and survival in progressive supranuclear palsy. J

Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2019;90:555-61. Crossref

10. Cosseddu M, Benussi A, Gazzina S, et

al. Natural history and predictors of survival in progressive supranuclear

palsy. J Neurol Sci 2017;382:105-7. Crossref

11. Chiu WZ, Kaat LD, Seelaar H, et al.

Survival in progressive supranuclear palsy and frontotemporal dementia. J

Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2010;81:441-5. Crossref

12. Dell’Aquila C, Zoccolella S, Cardinali

V, et al. Predictors of survival in a series of clinically diagnosed

progressive supranuclear palsy patients. Parkinsonism Relat Disord

2013;19:980-5. Crossref

13. Santacruz P, Uttl B, Litvan I, Grafman

J. Progressive supranuclear palsy: a survey of the disease course.

Neurology 1998;50:1637-47. Crossref

Litvan I, Mangone CA, McKee A, et al.

Natural history of progressive supranuclear palsy

(Steele-Richardson-Olszewski syndrome) and clinical predictors of

survival: a clinicopathological study. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry

1996;60:615-20. Crossref

15. O’Sullivan SS, Massey LA, Williams DR,

et al. Clinical outcomes of progressive supranuclear palsy and multiple

system atrophy. Brain 2008;131:1362-72. Crossref

16. Papapetropoulos S, Gonzalez J, Mash

DC. Natural history of progressive supranuclear palsy: a clinicopathologic

study from a population of brain donors. Eur Neurol 2005;54:1-9. Crossref

17. Shea YF, Ha J, Chu LW. Progressive

supranuclear palsy presenting initially as semantic dementia. J Am Geriatr

Soc 2014;62:2459-60. Crossref

18. Chiu HF, Lee HC, Chung WS, Kwong PK.

Reliability and validity of Cantonese version of the Mini-Mental State

Examination: a preliminary study. J Hong Kong Col Psych 1994;4:25-8.

19. Prosser L, Canby A. Further validation

of the elderly mobility scale for measurement of mobility of hospitalized

elderly people. Clin Rehabil 1997;11:338-43. Crossref

20. Tomita S, Oeda T, Umemura A, et al.

Impact of aspiration pneumonia on the clinical course of progressive

supranuclear palsy: a retrospective cohort study. PLoS One

2015;10:e0135823. Crossref

21. Rosenbek JC, Robbins JA, Roecker EB,

Coyle JL, Wood JL. A penetration-aspiration scale. Dysphagia 1996;11:93-8.

Crossref

22. Edsberg LE, Black JM, Goldberg M,

McNichol L, Moore L, Sieggreen M. Revised national pressure ulcer advisory

panel pressure injury staging system: revised pressure injury staging

system. J Wound Ostomy Continence Nurs 2016;43:585-97. Crossref

23. Testa D, Monza D, Ferrarini M,

Soliveri P, Girotti F, Filippini G. Comparison of natural histories of

progressive supranuclear palsy and multiple system atrophy. Neurol Sci

2001;22:247-51. Crossref

24. Diroma C, Dell’Aquila C, Fraddosio A,

et al. Natural history and clinical features of progressive supranuclear

palsy: a clinical study. Neurol Sci 2003;24:176-7. Crossref

25. Goetz CG, Leurgans S, Lang AE, Litvan

I. Progression of gait, speech and swallowing deficits in progressive

supranuclear palsy. Neurology 2003;60:917-22. Crossref

26. Jecmenica-Lukic M, Petrovic IN,

Pekmezovic T, Kostic VS. Clinical outcomes of two main variants of

progressive supranuclear palsy and multiple system atrophy: a prospective

natural history study. J Neurol 2014;261:1575-83. Crossref

27. Litvan I, Kong M. Rate of decline in

progressive supranuclear palsy. Mov Disord 2014;29:463-8. Crossref

28. Ou R, Liu H, Hou Y, et al. Executive

dysfunction, behavioral changes and quality of life in Chinese patients

with progressive supranuclear palsy. J Neurol Sci 2017;380:182-6. Crossref

29. Luk JK, Chan DK. Preventing aspiration

pneumonia in older people: do we have the ‘know-how’? Hong Kong Med J

2014;20:421-7. Crossref

30. Lansdall CJ, Coyle-Gilchrist IT,

Vázquez Rodríguez P, et al. Prognostic importance of apathy in syndromes

associated with frontotemporal lobar degeneration. Neurology

2019;92:e1547-57. Crossref