© Hong Kong Academy of Medicine. CC BY-NC-ND 4.0

COMMENTARY

Colonic actinomycosis: a pseudo-tumour that mimics

colonic neoplasm

KW Hui, MB, ChB; Bryant SY Chan, MB, BS, FRCS;

Kenny KY Yuen, MB, BS, FRCS

Department of Surgery, Tseung Kwan O Hospital,

Tseung Kwan O, Hong Kong

Corresponding author: Dr KW Hui (karen.hui@icloud.com)

Introduction

Actinomyces is a class of Gram-positive,

non-acid-fast, anaerobic-to-microaerophilic bacteria commonly

found in the oral cavity. It is known for its causative role in oral

infections after dental procedures. Abdominopelvic involvement is

uncommon, with few reported cases. Risk factors of intra-abdominal

actinomycosis include use of intrauterine device, abdominal or pelvic

procedures, and various causes of intestinal necrosis.1 Current understanding on intra-abdominal actinomycosis

has highlighted its inclination to mimic neoplasm. Reported cases on organ

dissemination and progression to fistulae formation further confound this

diagnostic challenge in clinical practice. Although perforation of

neoplasm remains the primary concern in septic manifestations of an

abdominal mass lesion, infective differentials such as actinomycosis

should be considered. Because the presentation of acute abdomen

necessitates timely treatment, early operative treatment is often favoured

by clinicians, particularly when complications such as sepsis and

intestinal obstruction arise. This leaves limited scope for

investigations. As a result, the diagnosis of intra-abdominal

actinomycosis is often established from pathological assessment after

cure.

Exemplar local case

A 35-year-old woman with good past health presented

to Tseung Kwan O Hospital, Hong Kong, in December 2017, with 1-month

history of right lower abdominal discomfort and low-grade fever. Abdominal

examination identified an 8-cm tender right lower quadrant mass with local

guarding and rebound tenderness. Blood tests showed neutrophil predominant

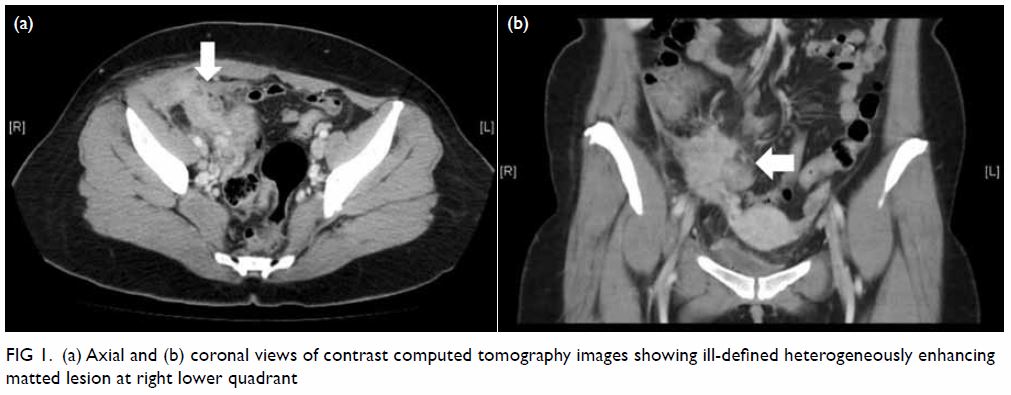

leukocytosis (17.2 × 109/L). Urgent contrast enhanced computed

tomography scan of the pelvis revealed an ill-defined heterogeneously

enhancing mass at right lower abdomen with matted manifestations in its

vicinity, involving an oedematous terminal ileal segment and

gynaecological organs (Fig 1). The patient underwent diagnostic laparoscopy

with revelation of an 8-cm locally invasive firm mass arising from the

caecum. Dense adhesions to the colonic mesentery and terminal ileum were

dissected free. The right infundibulopelvic ligament and right base of

ovary appeared to be invaded by the colonic pseudo-tumour. The procedure

proceeded to an en bloc resection including formal right hemicolectomy and

right salpingo-oophorectomy. The patient had an uneventful postoperative

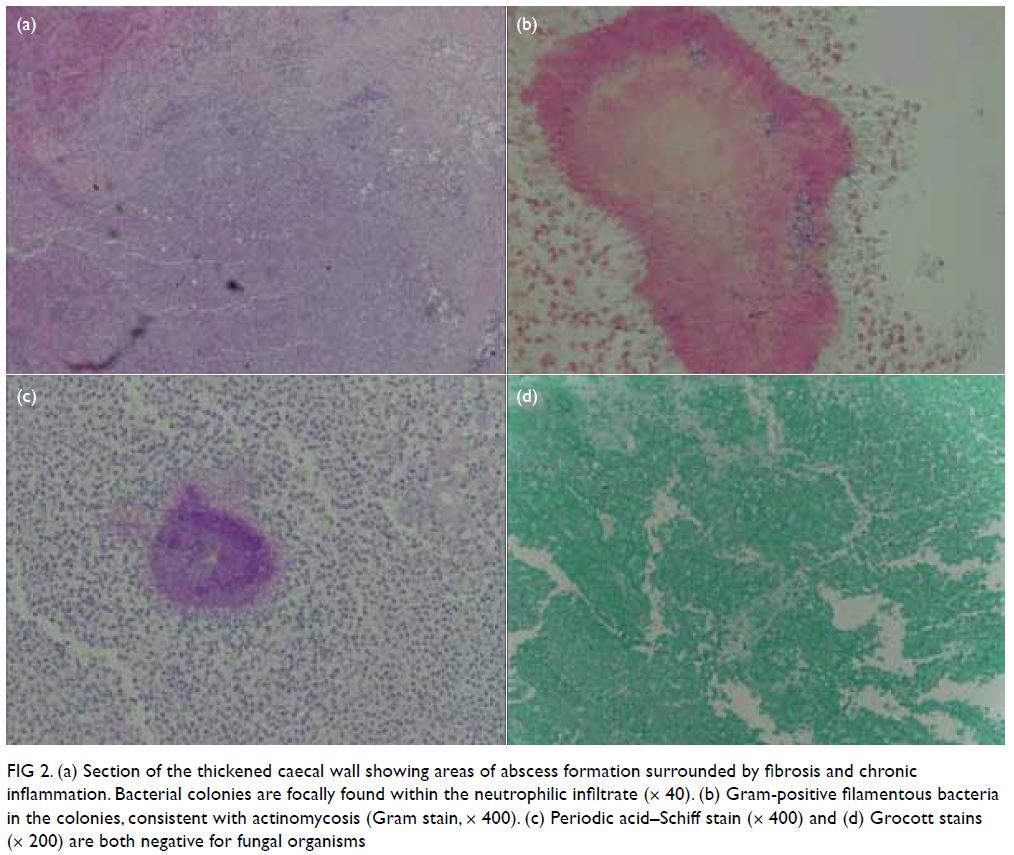

recovery course. Pathological examination of the specimen (Fig

2) unveiled histological diagnosis of disseminated actinomycosis

with abscess, fibrosis, and inflammation extending into adjacent

mesenteric tissue, mesoappendix, mesosalpinx, and adhering fibrofatty

tissue.

Figure 1. (a) Axial and (b) coronal views of contrast computed tomography images showing ill-defined heterogeneously enhancing matted lesion at right lower quadrant

Figure 2. (a) Section of the thickened caecal wall showing areas of abscess formation surrounded by fibrosis and chronic inflammation. Bacterial colonies are focally found within the neutrophilic infiltrate (× 40). (b) Gram-positive filamentous bacteria in the colonies, consistent with actinomycosis (Gram stain, × 400). (c) Periodic acid–Schiff stain (× 400) and (d) Grocott stains (× 200) are both negative for fungal organisms

How to investigate actinomycosis

The current role of imaging in the diagnosis of

intra-abdominal or pelvic actinomycosis is poorly defined. Limited studies

have suggested some computed tomographic features of actinomycosis

describing its infiltrative nature and tendency to invade across tissue

plane and boundaries. Dense inhomogeneous contrast enhancement in walls or

solid component of masses and minimal lymphadenopathy may also be

characteristic.2 However, the

features are often insufficient to help distinguish the condition from

most other differentials. Kim et al3

investigated the efficacy of combining colonoscopy and computed

tomography. In future, combined investigations are expected to gain

popularity, to take advantage of complementary imaging modalities. Degree

of stenosis and mucosal abnormalities are other areas being further

evaluated for imaging studies. Cytological investigations are effective

but limited to variants of actinomycosis such as multi-cystic subtypes.

Image-guided fine needle aspiration may identify actinomycotic granules on

microscopy and facilitate bacterial culture.4

Currently, most clinicians remain reluctant to consider cytological or

tissue samples to avoid the possibility of tumour seeding before a certain

diagnosis has been made.5

How to treat actinomycosis

Owing to the scarcity of reported cases of

actinomycosis, a standardised management protocol is lacking to date.

Evans et al5 advocate antibiotic therapy to obliterate the disease, while

proceeding to extensive resection for the purpose of debulking. High-dose

penicillin is an established first-line regimen in the treatment of

actinomycosis. Doxycycline and clindamycin are alternatives, especially in

patients with penicillin allergy. Prolonged course of antibiotics

postoperatively up to 6 to 12 months until sign of disease clearance is

advocated by some. In view of the tendency of actinomycosis to spread

across tissue planes and disseminate to other organs, surgical resection

may be extensive. Preoperative counselling on possible extent of surgery

is crucial in all cases where actinomycosis is considered.

Prospects

Intra-abdominal actinomycosis is uncommon

worldwide. Imaging and cytological investigations are shown to be useful

but their roles in establishing definitive diagnosis are yet to be

defined. Preliminary studies on combined imaging have demonstrated

promising results. However, a lack of consensus remains over antibiotic

therapy alone versus antibiotic therapy with additional debulking surgery.

Prognosis of the disease entity remains unclear. An evidence-based

management protocol will help standardise care of this rare disease entity

as we gain more understanding from additional cases over time.

Author contributions

All authors had full access to the data,

contributed to the study, approved the final version for publication, and

take responsibility for its accuracy and integrity.

Concept or design of the study: KW Hui, BSY Chan.

Acquisition of data: KW Hui, BSY Chan.

Analysis or interpretation of data: KW Hui, BSY Chan.

Drafting of the article: KW Hui.

Critical revision for important intellectual content: All authors.

Acquisition of data: KW Hui, BSY Chan.

Analysis or interpretation of data: KW Hui, BSY Chan.

Drafting of the article: KW Hui.

Critical revision for important intellectual content: All authors.

Conflicts of interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest to

disclose.

Funding/support

This research received no specific grant from any

funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Ethics approval

This study was conducted in accordance with the

principles outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki. Informed consent has

been obtained from patient for the treatment.

References

1. Filippou D, Psimitis I, Zizi D, Rizos S.

A rare case of ascending colon actinomycosis mimicking cancer. BMC

Gastroenterol 2005;5:1. Crossref

2. Ha HK, Lee HJ, Kim H, et al. Abdominal

actinomycosis: CT findings in 10 patients. AJR Am J Roentgenol

1993;161:791-4. Crossref

3. Kim JC, Ahn BY, Kim HC, et al.

Efficiency of combined colonoscopy and computed tomography for diagnosis

of colonic actinomycosis: a retrospective evaluation of eight consecutive

patients. Int J Colorectal Dis 2000;15:236-42. Crossref

4. Cameron AE, Menon GG, Wyatt AP.

Abdominal actinomycosis mimicking carcinomatosis. J R Soc Med

1988;81:231-2. Crossref

5. Evans J, Chan C, Gluch L, Fielding I,

Eckstein R. Inflammatory pseudotumour secondary to actinomyces infection.

Aust N Z J Surg 1999;69:467-9. Crossref