© Hong Kong Academy of Medicine. CC BY-NC-ND 4.0

COMMENTARY

Transcatheter arterial embolisation can be the

standard treatment for non-variceal upper gastrointestinal bleeding

refractory to endoscopy

HF Chan, FHKAM (Radiology)1; KW Lai,

FHKAM (Surgery)2; Alfred WT Yung, FHKAM (Radiology)1;

WH Luk, FHKAM (Radiology)1; LF Cheng, FHKAM (Radiology)1;

Johnny KF Ma, FHKAM (Radiology)1

1 Department of Radiology, Princess

Margaret Hospital, Laichikok, Hong Kong

2 Department of Surgery, Princess

Margaret Hospital, Laichikok, Hong Kong

Corresponding author: Dr HF Chan (chf178@ha.org.hk)

Introduction

Endoscopic treatment is the standard first-line

management for non-variceal upper gastrointestinal (GI) bleeding.

Recurrent bleeding occurs in about 10% to 15% of patients after the first

endoscopy and is associated with significant mortality.1 Surgery has hitherto been the traditional treatment for

non-variceal upper GI bleeding refractory to endoscopy. In recent years,

transcatheter arterial embolisation (TAE) has been shown to be equally

effective in control of bleeding and associated with fewer complications.2 3

4 5

6 Moreover, TAE avoids the risks

associated with general anaesthesia. In our centre, TAE is the standard

next step for endoscopy-refractory non-variceal upper GI bleeding. We

believe that this practice can also be adopted in other centres where

interventional radiology expertise and facilities are available.

Exemplar case

We experienced an 89-year-old woman with multiple

medical co-morbidities including hypertension, mitral valve regurgitation,

congestive heart failure, diabetes mellitus, and chronic obstructive

airway disorder. The patient was admitted to Princess Margaret Hospital on

29 March 2017 with massive haematemesis. On admission her blood pressure

was 105/60 mm Hg, heart rate 100 beats per minute, and oxygen saturation

97% in room air. Pallor was noted on physical examination and per rectal

exam was empty. Blood results revealed a haemoglobin level 8.1 g/dL,

platelet count 225 × 109/L, international normalised ratio 1.0, creatinine

level 144 μmol/L, and urea level 17 mmol/L. First

oesophagogastroduodenoscopy (OGD) arranged on the same day immediately

following admission revealed a 3-cm roll-edged ulcer (Forrest IIa) at the

fundus of the greater curvature. Biopsy was taken. Haemostasis was

achieved by endoscopic application of one haemoclip and injection of 4 mL

adrenaline 1:10000. An intravenous proton pump inhibitor was started but

the patient developed a further massive haematemesis a few hours later.

Repeat OGD revealed a large adherent clot over the same ulcer. After

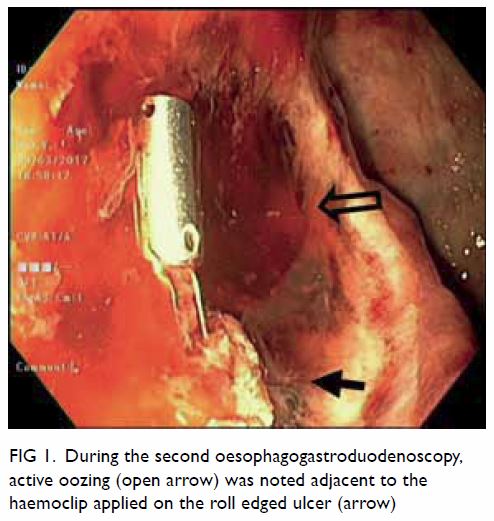

removing the clot, spurting was noted adjacent to the haemoclip (Fig

1). Endoscopic interventions included adrenaline injection (totally

13 mL 1:10000 adrenaline) and application of haemoclips and haemospray.

Despite these measures the patient became haemodynamically unstable during

the procedure and required urgent intubation by an anaesthetist for airway

protection. The patient also required large-volume blood product

transfusion and high-dose inotrope.

Figure 1. During the second oesophagogastroduodenoscopy, active oozing (open arrow) was noted adjacent to the haemoclip applied on the roll edged ulcer (arrow)

The intervention radiologist was consulted urgently

and the patient directly transferred from the endoscopy centre to the

interventional radiology suite about 1 hour after completion of the second

OGD. Arterial access was obtained at the right common femoral artery.

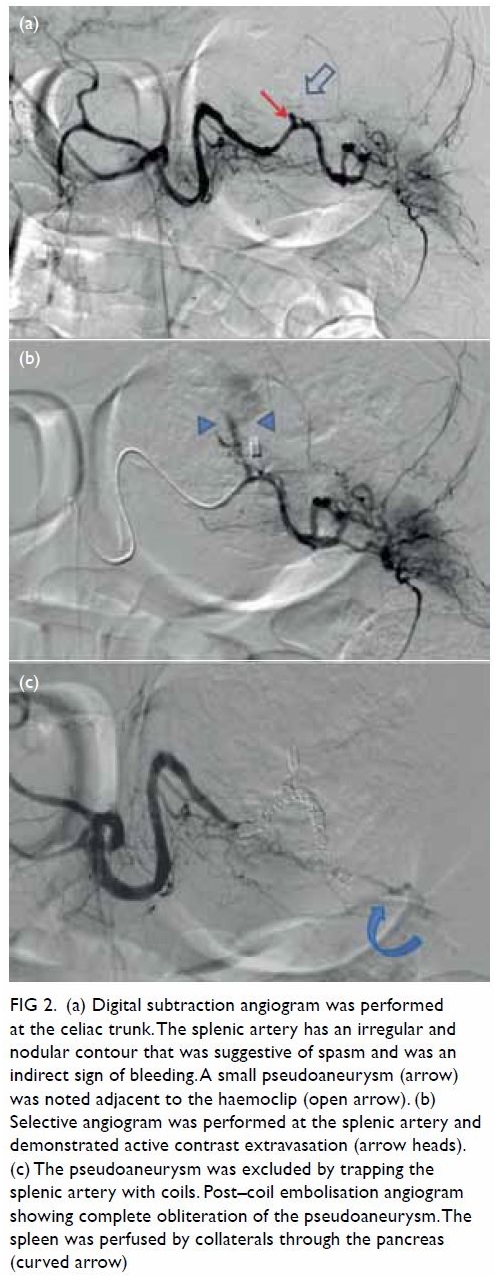

Celiac artery angiogram revealed a pseudoaneurysm at the mid splenic

artery, corresponding to the site of haemoclip on digital subtraction

angiogram image. Selective angiogram of the splenic artery confirmed the

finding of pseudoaneurysm and active extravasation from the pseudoaneurysm

was demonstrated. Exclusion of the pseudoaneurysm was achieved using a

sandwich embolisation technique at distal, and across and proximal to the

neck of the pseudoaneurysm, blocking the efferent (back door) and afferent

splenic artery (front door). Seven fibered platinum coils were used.

Post-embolisation angiogram confirmed the pseudoaneurysm had been

obliterated. Normal blood flow to the spleen was also obliterated and the

spleen was perfused by collaterals from the pancreas (Fig

2). The total procedure time for angiogram and embolisation was

about 45 minutes. The patient’s haemodynamic status and haemoglobin level

rapidly stabilised after the procedure. During resuscitation, the patient

received a total of 1 L gelofusine, 7 units of packed cells, 4 units of

fresh frozen plasma, and 4 units of platelet concentrate.

Figure 2. (a) Digital subtraction angiogram was performed at the celiac trunk. The splenic artery has an irregular and nodular contour that was suggestive of spasm and was an indirect sign of bleeding. A small pseudoaneurysm (arrow) was noted adjacent to the haemoclip (open arrow). (b) Selective angiogram was performed at the splenic artery and demonstrated active contrast extravasation (arrow heads). (c) The pseudoaneurysm was excluded by trapping the splenic artery with coils. Post–coil embolisation angiogram showing complete obliteration of the pseudoaneurysm. The spleen was perfused by collaterals through the pancreas (curved arrow)

The patient was extubated the next day. Her

condition continued to improve, and the patient was discharged to a

convalescence hospital 2 weeks later. She did not present with any signs

or symptoms of splenic infarct. The pathology report of the gastric ulcer

confirmed it as benign. To date, the patient has not presented with any

signs or symptoms of upper GI bleeding or significant haemoglobin drop.

Follow-up OGD was not arranged in view of the patient’s advanced age and

because it would be unlikely to influence subsequent management. The

splenic artery pseudoaneurysm appeared to be caused by a benign gastric

ulcer at the greater curvature eroding into the splenic artery. Fewer than

10 such cases have been reported in the English literature. The successful

management of this case of rare massive upper GI bleeding highlights the

importance of collaboration between endoscopist, anaesthetist, and

interventional radiologist. Timely involvement of an interventional

radiologist after failed endoscopic haemostasis not only allows rapid

diagnosis of the underlying aetiology but also allows embolisation to stop

bleeding at the same time.

Transcatheter arterial embolisation versus surgery

To date, there has been no prospective controlled

trial to compare TAE with surgery in non-variceal upper GI bleeding

refractory to endoscopic treatment. Nevertheless the efficacy of TAE in

terms of technical success (62%-100%) and clinical success (44%-99%) has

been demonstrated in several case series.7

8 9

10 11

12 More importantly, a number of

retrospective studies comparing the two strategies favour the use of TAE.2 3

4 5

6 They show that TAE is equally

effective in bleeding control, has a low complication rate and does not

increase mortality, even though patients in the TAE group tended to have a

higher surgical risk.2 3 4 5 6

Embolisation technique

The source of bleeding is often first identified at

endoscopy, guiding subsequent angiography, and TAE. The principle of TAE

is to selectively obstruct or reduce blood flow to the bleeding point and

minimise ischaemia in the rest of the GI tract. Generally speaking, the

risk of ischaemia in upper GI bleeding is small because of the rich

collateral circulation in the stomach and duodenum.13 The rich collateral arterial network in the upper GI

tract nonetheless also causes treatment failure as blood flow to the

bleeding point may persist through retrograde flow from collaterals.13 This problem can be overcome by superselective

embolisation of the bleeder branch using a small microcatheter.12 When contrast extravasation or pseudoaneurysm is

detected in a large vessel such as the gastroduodenal artery or left

gastric artery, the artery can be trapped by coils placed across the point

of extravasation or pseudoaneurysm, so as to close the “front door” and

“back door”.13 Recently,

impressive results have been reported with superselective embolisation

using N-butyl cyanoacrylate glue.12

13 N-butyl cyanoacrylate

embolisation has a shorter procedure time and occludes the target vessel

independent of the patient’s coagulation system. It is particularly useful

in patients who are haemodynamically unstable or coagulopathic.

Practical considerations

Successful performance of TAE relies on centre

expertise. The published studies of TAE were performed in high-volume

centres with a specialist interventional radiology service. The results

might not be reproducible in smaller centres. Another consideration is the

availability of an interventional radiologist and angiography suite

out-of-hours. Longer time to angiography was found to predict early

rebleeding and every effort should be made to perform TAE early, even

outside office hours. Lack of access to a 24-hour interventional radiology

service in smaller centres is a major barrier to the routine use of TAE.

Conclusion

Transcatheter arterial embolisation is an effective

and safe treatment and compares favourably with surgery in the management

of endoscopy-refractory non-variceal upper GI bleeding. In centres where

expertise and facilities are available, TAE can be considered the routine

next step management when endoscopy fails to control bleeding.

Author contributions

All authors had full access to the data,

contributed to the study, approved the final version for publication, and

take responsibility for its accuracy and integrity.

Concept and design: All authors.

Acquisition of data: HF Chan.

Analysis or interpretation of data: All authors.

Drafting of the manuscript: All authors.

Critical revision for important intellectual content: All authors.

Acquisition of data: HF Chan.

Analysis or interpretation of data: All authors.

Drafting of the manuscript: All authors.

Critical revision for important intellectual content: All authors.

Conflicts of interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest to

disclose.

Funding/support

This research received no specific grant from any

funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Ethics approval

The patient was treated in accordance with the

Declaration of Helsinki. The patient provided informed consent for all

procedures.

References

1. Jairath V, Kahan BC, Logan RF, et al.

National audit of the use of surgery and radiological embolization after

failed endoscopic haemostasis for non-variceal upper gastrointestinal

bleeding. Br J Surg 2012;99:1672-80. Crossref

2. Ang D, Teo EK, Tan A, et al. A

comparison of surgery versus transcatheter angiographic embolization in

the treatment of nonvariceal upper gastrointestinal bleeding uncontrolled

by endoscopy. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2012;24:929-38. Crossref

3. Wong TC, Wong KT, Chiu PW, et al. A

comparison of angiographic embolization with surgery after failed

endoscopic hemostasis to bleeding peptic ulcers. Gastrointest Endosc

2011;73:900-8. Crossref

4. Venclauskas L, Bratlie SO, Zachrisson K,

Maleckas A, Pundzius J, Jönson C. Is transcatheter arterial embolization a

safer alternative than surgery when endoscopic therapy fails in bleeding

duodenal ulcer? Scand J Gastroenterol 2010;45:299-304. Crossref

5. Ripoll C, Bañares R, Beceiro I, et al.

Comparison of transcatheter arterial embolization and surgery for

treatment of bleeding peptic ulcer after endoscopic treatment failure. J

Vasc Interv Radiol 2004;15:447-50. Crossref

6. Eriksson LG, Ljungdahl M, Sundbom M,

Nyman R. Transcatheter arterial embolization versus surgery in the

treatment of upper gastrointestinal bleeding after therapeutic endoscopy

failure. J Vasc Interv Radiol 2008;19:1413-8. Crossref

7. Loffroy R, Guiu B, D’Athis P, et al.

Arterial embolotherapy for endoscopically unmanageable acute

gastroduodenal hemorrhage: predictors of early rebleeding. Clin

Gastroenterol Hepatol 2009;7:515-23. Crossref

8. Aina R, Oliva VL, Therasse E, et al.

Arterial embolotherapy for upper gastrointestinal hemorrhage: outcome

assessment. J Vasc Interv Radiol 2001;12:195-200. Crossref

9. Toyoda H, Nakano S, Takeda I, et al.

Transcatheter arterial embolization for massive bleeding from duodenal

ulcers not controlled by endoscopic hemostasis. Endoscopy 1995;27:304-7. Crossref

10. De Wispelaere JF, De Ronde T, Trigaux

JP, de Canniére L, De Geeter T. Duodenal ulcer hemorrhage treated by

embolization: results in 28 patients. Acta Gastroenterol Belg

2002;65:6-11.

11. Dempsey DT, Burke DR, Reilly RS,

McLean GK, Rosato EF. Angiography in poor-risk patients with massive

nonvariceal upper gastrointestinal bleeding. Am J Surg 1990;159:282-6. Crossref

12. Hur S, Jae HJ, Lee H, Lee M, Kim HC,

Chung JW. Superselective embolization for arterial upper gastrointestinal

bleeding using N-butyl cyanoacrylate: a single-center experience in 152

patients. J Vasc Interv Radiol 2017;28:1673-80. Crossref

13. Loffroy R, Favelier S, Pottecher P, et

al. Transcatheter arterial embolization for acute nonvariceal upper

gastrointestinal bleeding: Indications, techniques and outcomes. Diagn

Interv Imaging 2015;96:731-44. Crossref