© Hong Kong Academy of Medicine. CC BY-NC-ND 4.0

CASE REPORT

Hashimoto’s encephalopathy with partial

response to steroid therapy: a case report

Bahar Kaymakamzade, MD1; Senem Ertugrul

Mut, MD1; Amber Eker, MD1; Hanife Özkayalar, MD2

1 Department of Neurology, Near East

University Faculty of Medicine, Nicosia, Cyprus

2 Department of Pathology, Near East

University Faculty of Medicine, Nicosia, Cyprus

Corresponding author: Dr Senem Ertugrul Mut (senemertugrul@yahoo.com)

Case report

Hashimoto’s encephalopathy (HE), also termed as

steroid responsive encephalopathy associated with autoimmune thyroiditis,

is a rare and highly variable clinical spectrum. The clinical presentation

includes seizures, stroke-like episodes, cognitive decline,

neuropsychiatric symptoms, and myoclonus.1

We report a rare and unusual case of HE in which there was a partial

response to steroid therapy.

A 76-year-old man was admitted to the Department of

Neurology of the Near East University Hospital, Cyprus, in October 2016

with the chief complaint of myoclonic jerks and walking difficulty for the

past 6 weeks. The patient’s family had observed no significant cognitive

or behavioural change. He did not experience any seizure. His medical

history included hypertension and diabetes. On neurological examination he

was alert and fully oriented. Motor weakness was noted at the left lower

extremity with Babinski sign. He had myoclonus in all limbs and bilateral

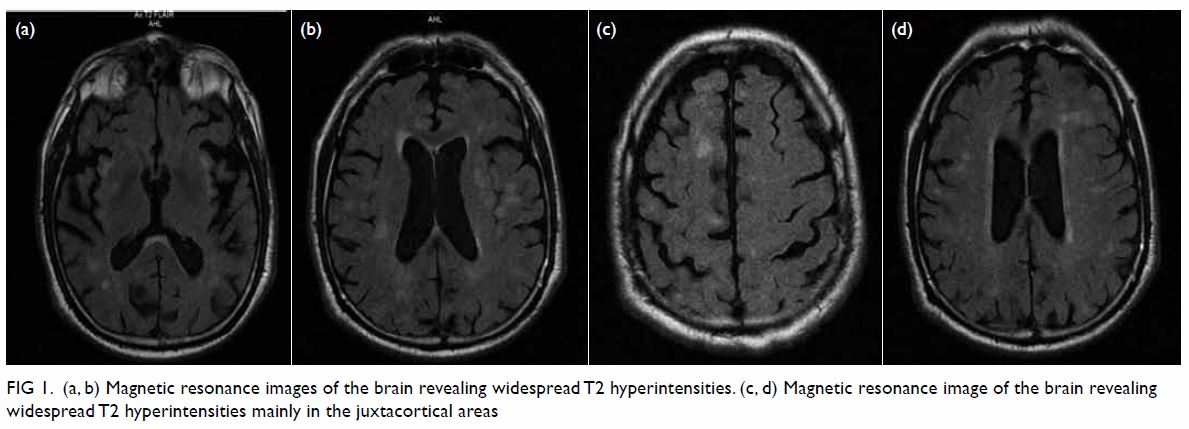

postural tremor, which was predominantly left sided. Magnetic resonance

imaging (MRI) scan of the brain revealed widespread T2 hyperintensities

mainly in the juxtacortical areas (Fig 1). Blood studies including complete blood count

and electrolyte count; liver, renal and thyroid function tests; tumour

markers; and paraneoplastic antibody analysis (anti-Hu, -Yo, -Ri, -Ma,

-CV2) were all normal. Vasculitis markers including antinuclear

antibodies, anti-ds DNA, anticardiolipin immunoglobulin (Ig) M, IgG

antibodies, antiphosphatidylserine IgM, IgG antibodies, perinuclear

antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies, cytoplasmic antineutrophil

cytoplasmic antibodies, anti-La and anti-Ro antibodies, and rheumatoid

factor were within normal limits. He tested negative for human

immunodeficiency virus. His cognitive status worsened during his first

week of hospitalisation and he rapidly developed delusions and aggressive

behaviour. He was not able to cooperate with the neurocognitive

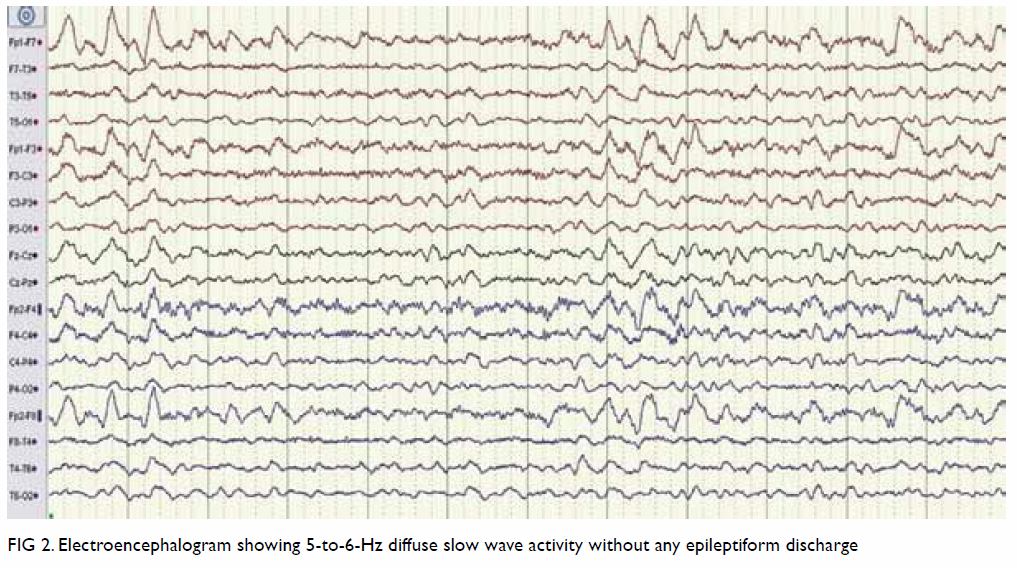

assessment. Electroencephalogram showed 5 to 6 Hz diffuse slow-wave

activity without any epileptiform discharge (Fig 2). Cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) analysis showed a

very high protein content (1.95 g/L). The CSF/serum glucose ratio was

normal. Cerebrospinal fluid investigation and culture was negative,

excluding central nervous system infection. Whole-body positron emission

tomography was performed to exclude paraneoplastic processes and the

result was normal. Consequently, steroid-responsive encephalopathy and

associated autoimmune thyroiditis was suspected, and antithyroglobulin

antibody (anti-TG-Ab) and antithyroperoxidase antibody (anti-TPO-Ab)

levels were studied. Serum level of both was increased (431 IU/mL and 40

IU/mL respectively). He was not taking any medication (eg, lithium,

amiodarone, etc) that could account for the positivity of thyroid

antibodies. Thyroid ultrasonography did not show any pathological

findings. Intravenous pulse steroid treatment (IVPS, methylprednisolone 1

g/day) was started. Myoclonus resolved on the fourth day of treatment.

Because the cognitive status of the patient was not adequately changed,

IVPS was extended to 10 days. A partial response was obtained in cognition

and Mini-Mental State Examination score was 11/30 after IVPS. Another

electroencephalogram showed mild improvement. Consequently, oral

methylprednisolone was continued at a dosage of 1 mg/kg/day. Afterwards,

intravenous Ig treatment was given at a dose of 0.4 g/kg for 5 days. No

additional improvement was seen. Lumbar puncture and thyroid autoantibody

testing were repeated. The anti-TPO-Ab and anti-TG-Ab levels were

normalised, and CSF was acellular at that time and protein content

decreased (1.45 g/L). Azathioprine 100 mg/day was gradually added to his

treatment. The patient was discharged from the hospital with oral steroid

and azathioprine treatment. His neurological status was stable. He died 3

months later due to a lung infection.

Figure 1. (a, b) Magnetic resonance images of the brain revealing widespread T2 hyperintensities. (c, d) Magnetic resonance image of the brain revealing widespread T2 hyperintensities mainly in the juxtacortical areas

Figure 2. Electroencephalogram showing 5-to-6-Hz diffuse slow wave activity without any epileptiform discharge

Discussion

The clinical findings, CSF analysis, and MRI of our

patient were compatible with HE. The challenging conditions we faced were

the lack of prominent cognitive or psychiatric change at the beginning and

normal thyroid functions. The differential diagnosis included vasculitis,

paraneoplastic limbic encephalitis, and Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease (CJD).

The MRI was very helpful for differential diagnosis. The pattern of

isolated cortical hyperintensity with concomitant combined cortical and

deep grey matter (basal ganglia) hyperintensity on fluid attenuation

inversion recovery along with restricted diffusion can differentiate CJD

from other rapidly progressive dementias with a high sensitivity and

specificity.2 Because the

consecutive diffusion-weighted images of the patient were not compatible

with CJD, 14-3-3 assay in the CSF was not studied. In addition, it is not

specific for CJD and its positivity is also reported in HE.3 The laboratory and imaging findings were not compatible

with limbic encephalitis. We assessed his objective clinical recovery

(dramatic disappearance of myoclonus and partial cognitive-behavioural

improvement) following pulse steroid therapy. Response to treatment may

also exclude the diagnosis of CJD.

The pathophysiology of HE is not well understood.

Autoimmune cerebral vasculitis and antibody-mediated neuronal reaction are

the most accepted mechanisms. Most patients are euthyroid at the time of

diagnosis.4 Antithyroperoxidase

antibody is known as a positive predictor of responsiveness to steroid

therapy and higher titres are associated with a more favourable outcome.5 Most cases in the literature

treated with steroids make a complete recovery.5

Since it is a rare condition, the optimum treatment for steroid-resistant

cases is unknown. Response to intravenous Ig or plasmapheresis treatments

in steroid non-responsive cases has also been reported.5 Despite the normalisation of anti-TPO-Ab and anti-TG-Ab

levels and somewhat improved inflammatory findings of CSF after treatment,

we observed a complete response in myoclonus and only a partial

improvement in cognition in our patient. This supports the hypothesis that

thyroid autoantibodies are not the only pathogenic mechanism in HE. Other

causes, the role of the thyroid gland, and other antibodies should be

clarified by future studies.

Author contributions

Concept or design: B Kaymakamzade, S Ertugrul Mut.

Acquisition of data: H Özkayalar, A Eker, S Ertugrul Mut.

Analysis or interpretation of data: B Kaymakamzade.

Drafting of the manuscript: All authors.

Critical revision for important intellectual content: S Ertugrul Mut, B Kaymakamzade.

Acquisition of data: H Özkayalar, A Eker, S Ertugrul Mut.

Analysis or interpretation of data: B Kaymakamzade.

Drafting of the manuscript: All authors.

Critical revision for important intellectual content: S Ertugrul Mut, B Kaymakamzade.

All authors had full access to the data,

contributed to the study, approved the final version for publication, and

take responsibility for its accuracy and integrity.

Acknowledgements

We thank Dr Mustafa Canatan and Dr Fehim Türktan

for their contribution to the editing of the manuscript.

Conflicts of interest

All authors have disclosed no conflicts of

interest.

Funding/support

This research received no specific grant from any

funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Ethics approval

This study was conducted in accordance with the

principles outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki. The patient provided

written informed consent.

References

1. Mocellin R, Walterfang M, Velakoulis D.

Hashimoto’s encephalopathy: epidemiology, pathogenesis and management. CNS

Drugs 2007;21:799-811. Crossref

2. Vitali P, Maccagnano E, Caverzasi E, et

al. Diffusion-weighted MRI hyperintensity patterns differentiate CJD from

other rapid dementias. Neurology 2011;76:1711-9. Crossref

3. Hernández Echebarría LE, Saiz A, et al.

Detection of 14-3-3 protein in the CSF of a patient with Hashimoto’s

encephalopathy. Neurology 2000;54:1539-40. Crossref

4. Oide T, Tokuda T, Yazaki M, et al.

Anti-neuronal autoantibody in Hashimoto’s encephalopathy:

neuropathological, immunohistochemical, and biochemical analysis of two

patients. J Neurol Sci 2004;217:7-12. Crossref

5. Litmeier S, Prüss H, Witsch E, Witsch J.

Initial serum thyroid peroxidase antibodies and long-term outcomes in

SREAT. Acta Neurol Scand 2016;134:452-7. Crossref