Hong

Kong Med J 2019 Apr;25(2):113–9 | Epub 10 Apr 2019

© Hong Kong Academy of Medicine. CC BY-NC-ND 4.0

ORIGINAL ARTICLE

Infection control in residential care homes for the

elderly in Hong Kong (2005-2014)

Grace CY Wong, MB, ChB; Tonny Ng, MMed (Public

Health) Singapore, FHKAM (Community Medicine); Teresa Li, FFPH, FHKAM

(Community Medicine)

Elderly Health Service, Department of Health, Hong

Kong SAR Government, Hong Kong

Corresponding author: Dr Grace CY Wong (grace_cy_wong@dh.gov.hk)

Abstract

Introduction: This serial

cross-sectional survey study aimed to review the trend in various

infection control practices in residential care homes for the elderly

(RCHEs) in Hong Kong from 2005 to 2014.

Methods: Annual cross-sectional

surveys were conducted at all RCHEs in Hong Kong, including

self-administered questionnaires, on-site interviews, inspections, and

assessments conducted by trained nurses, from 2005 to 2014. In all,

98.5% to 100% of all RCHEs were surveyed each year based on the list of

licensed RCHEs in Hong Kong.

Results: There was a substantial

increase in the proportion of RCHE residents aged ≥85 years, from 40.0%

in 2005 to 50.2% in 2014 (P=0.002). The percentage of RCHE residents

with special care needs also increased, from 22.3% in 2005 to 32.6% in

2014 for residents with dementia (P<0.001) and from 3.4% in 2005 to

5.0% in 2014 for residents with a long-term indwelling urinary catheter

(P<0.001). The proportion of RCHEs with separate rooms for isolation

areas ranged from 73.6% to 80% but did not show any significant trend

over the study period. The proportion of RCHEs with alcohol hand rub

available showed an increasing trend from 25.4% in 2006 to 99.2% in 2014

(P=0.008). The proportion of health or care workers (who were not the

designated infection control officers) passing skills tests on hand

washing techniques increased from 79.2% in 2006 to 91.5% in 2014

(P=0.02). An increasing trend was also observed for the proportion of

infection control officers who were able to prepare properly diluted

bleach solution, from 71.5% in 2005 to 92.2% in 2014 (P=0.002).

Conclusions: For infection

control practice to continue improving, more effort should

be made to enhance and maintain proper practice, and to mitigate the

challenge posed by the high turnover rates of healthcare workers in

RCHEs. Introduction of self-audits on infection control practices should

be considered.

New knowledge added by this study

- From 2005 to 2014, among residents of care homes for the elderly, the proportion of those aged ≥85 years increased significantly.

- If this trend continues, the prevalence of co-morbidities and functional impairment will also continue to increase, leading to further infection control challenges.

- There have been improvements in infection control practices among residential care homes for the elderly in terms of manpower, facilities, practices, knowledge, and skills.

- The most obvious improvements have been in terms of manpower and facilities; more nurses and health workers were recruited, and more residential care homes for the elderly had made alcohol hand rub available. Correct hand washing techniques among health or care workers, availability of alcohol hand rub, and knowledge on the correct method to prepare diluted bleach solution have also improved over the years.

- Improvements in infection control knowledge and skills among staff of residential care homes for the elderly have seemingly reached a plateau.

- Future infection control training should aim to support sustained compliance with proper practices, through the introduction of elements such as self-audits.

Introduction

Residential care services for elderly people in Hong

Kong

In 2016, 8.1% of elderly population in Hong Kong

resided in non-domestic households (ie, residential care homes for the

elderly [RCHEs], hospitals and penal institutions, etc).1 Residential care homes for the elderly are a

heterogeneous group of institutions that provide varying levels of care

for elderly people, who, for personal, social, health, or other reasons,

can no longer live alone or with their families.

There is a mix of government-subvented,

self-financed, and privately run RCHEs in Hong Kong. All RCHEs must be

licensed under the Residential Care Homes (Elderly Persons) Ordinance. The

RCHEs operate according to the code of practice (COP)2 issued by the licensing authority. The COP sets out

guidelines, principles, procedures, and standards for the operation and

management of RCHEs. A chapter in the COP is devoted to infection control,

requiring the RCHE’s operator to designate an infection control officer

(ICO). The ICO must coordinate and implement infection control measures

within the home according to the infection control guideline issued by the

Centre for Health Protection of the Department of Health.3 Operators of RCHEs are required to report specific

infectious disease cases and outbreaks to the authorities.

Visiting health teams

Eighteen visiting health teams (VHTs) are

established under the Elderly Health Service of the Department of Health

in Hong Kong. Comprising 47 nurses, the teams reach out into the community

and residential care settings to conduct health promotion activities for

the elderly people, and carers of elderly people, aiming to increase the

health awareness and the self-care ability of elderly people, and to

enhance the quality of caregiving.

The first on-site assessment covering all RCHEs in

Hong Kong on infection control performance was conducted by VHTs between

August and October 2003 as an enhanced measure in response to the severe

acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) outbreak. Since then, annual assessments

have been conducted by VHTs to assess and monitor the effectiveness of

infection control measures and to identify the training needs of

healthcare staff working in RCHEs, so as to plan for training activities

for the following year. Assessment results are shared with relevant

stakeholders, including the licensing authority and the community

geriatric teams of public hospitals which provide outreach personal

medical care to residents of RCHEs. Feedback is also provided to RCHE

staff, to increase their alertness and encourage improvements.

This study aimed to review the 10-year trend in

infection control practices in RCHEs in Hong Kong, based on results of the

annual VHT assessments conducted from 2005 to 2014.

Methods

Assessment of all RCHE facilities, and the

infection control knowledge and skills of staff are conducted annually via

structured questionnaires and observational checklists.

Sample size and coverage rate

The annual surveys cover all RCHEs in Hong Kong

from 2005 to 2014, based on the lists maintained by the licensing

authority.4 The coverage rate was

98.5% to 100% from 2005 to 2014. A few RCHEs were not covered because they

were either non-operating (under renovation or recently closed) or refused

the VHT service. These RCHEs were excluded from analysis.

Data collection

The surveys were conducted from August to October

each year, based on an assessment protocol developed by doctors and nurses

of the VHTs, and with reference to the COP,2 the prevailing “Guidelines on

Prevention of Communicable Diseases in Residential Care Home for the

Elderly”3 and overseas guidelines

on infection control practice.5 6 7

Resident demographics, staff profiles, information on environment and

facilities related to infection control, and knowledge and skills of the

ICO and other staff were collected in the surveys. The assessments were

divided into four parts:

Part I: The characteristics and profiles of

residents and staff of the RCHEs, including the subjective training needs

of staff, were collected through a self-administered questionnaire (online

supplementary Appendix) completed by the person-in-charge of the

RCHE, prior to the site visit by the VHT.

Part II: The environmental conditions and

facilities related to infection control in RCHEs were assessed by a VHT

nurse during the site visit.

Part III: The health monitoring and record keeping

practices in RCHEs were assessed during the site visit.

Part IV: The knowledge and skills on infection

control of staff in RCHEs were assessed in face-to-face interviews during

the site visit. The ICO (or other staff, depending on the topic being

assessed) of each RCHE was assessed. An additional member of staff (either

a health worker or care worker) was also selected at random for assessment

on hand washing technique.

After the assessments, data were either

double-entered or double-checked by two separate colleagues. In addition,

10% of the questionnaires were audited by an independent colleague, who

rechecked all questionnaires if the error rate detected was greater than

0.5% of data fields. Descriptive statistics on the characteristics of the

residents and the health/personal care staff were tabulated. Categorical

data were analysed by either Chi squared test or Fisher’s exact test while

trend analysis was conducted by linear regression. A linear trend is

reported as significant when the slope of the regression line is

statistically different from zero. All analyses were conducted using SPSS

(Windows version 24.0; IBM Corp, Armonk [NY], United States). This report

was prepared following the STROBE (Strengthening the Reporting of

Observational Studies in Epidemiology) statement.8

Results

The majority of RCHEs (ranging from 73.9% to 75.7%,

between 2005 and 2014) were commercially operated RCHEs (“private RCHEs”).

The remaining 24.3% to 26.1% were “non-private RCHEs”, comprising those

that received subsidies or subventions from the government and those that

were non–profit making and self-financing in nature.9

Part I: Characteristics of residents and staff of

residential care homes for the elderly

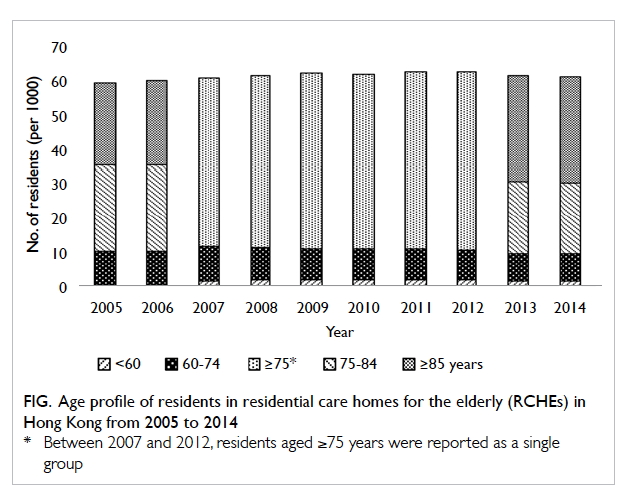

Age profile of residents

The age profile of the residents in RCHEs from 2005

to 2014 is shown in the Figure. An apparent ageing trend is observed with

the proportion of RCHE residents aged ≥85 years rising from 40.0% (23 718)

in 2005 to 50.2% (31 149) in 2014 (P=0.002).

Figure. Age profile of residents in residential care homes for the elderly (RCHEs) in Hong Kong from 2005 to 2014

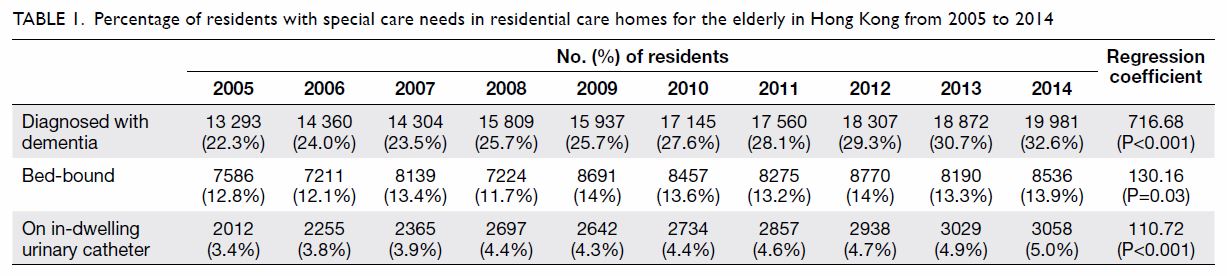

Residents with special care needs

Table 1 shows the percentage of residents with

special care needs from 2005 to 2014. The proportion of residents with

dementia increased from 22.3% in 2005 to 32.6% in 2014 (P<0.001). The

percentage of residents with a long-term indwelling urinary catheter

increased from 3.4% in 2005 to 5.0% in 2014 (P<0.001), representing a

47% increase in the number of patients with a long-term indwelling urinary

catheter.

Table 1. Percentage of residents with special care needs in residential care homes for the elderly in Hong Kong from 2005 to 2014

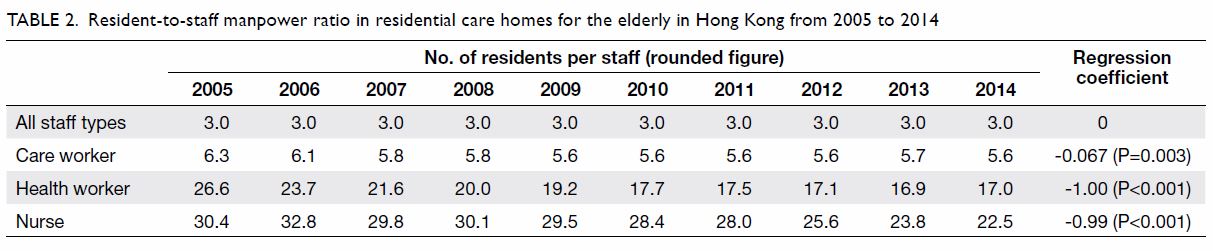

Manpower in residential care homes for the elderly

The resident-to-staff ratios in RCHEs from 2005 to

2014 are shown in Table 2. The major types of staff in RCHEs in Hong

Kong are professionally qualified nurses (including registered nurses and

enrolled nurses registered under the Nursing Council of Hong Kong), health

workers who have completed basic training recognised by the licensing

authority, care workers who have not received any official training, and

other staff including allied health and supporting staff. There were no

significant changes in overall resident-to-staff ratio over the study

period. For nurses and health workers, the overall manpower ratios

improved from 30:1 and 27:1 in 2005 to 23:1 and 17:1 in 2014, respectively

(both P<0.001). Increases in numbers of full-time and part-time nurses

and health workers contributed to the improvements in these ratios.

Table 2. Resident-to-staff manpower ratio in residential care homes for the elderly in Hong Kong from 2005 to 2014

There was an observable difference in terms of the

number of nurses between private RCHEs and non-private RCHEs. In 2014, the

resident-to-nurse ratio was 58:1 in private RCHEs compared with 11:1 in

non-private RCHEs. In fact, the majority of private RCHEs (70.9%) did not

employ any nursing staff. In contrast, only 3.8% of non-private RCHEs did

not have any nursing staff. Only 18.5% of private RCHEs had assigned

nurses as ICOs, whereas the percentage was 93.0% in non-private RCHEs. The

rest of the RCHEs appointed health workers as ICOs.

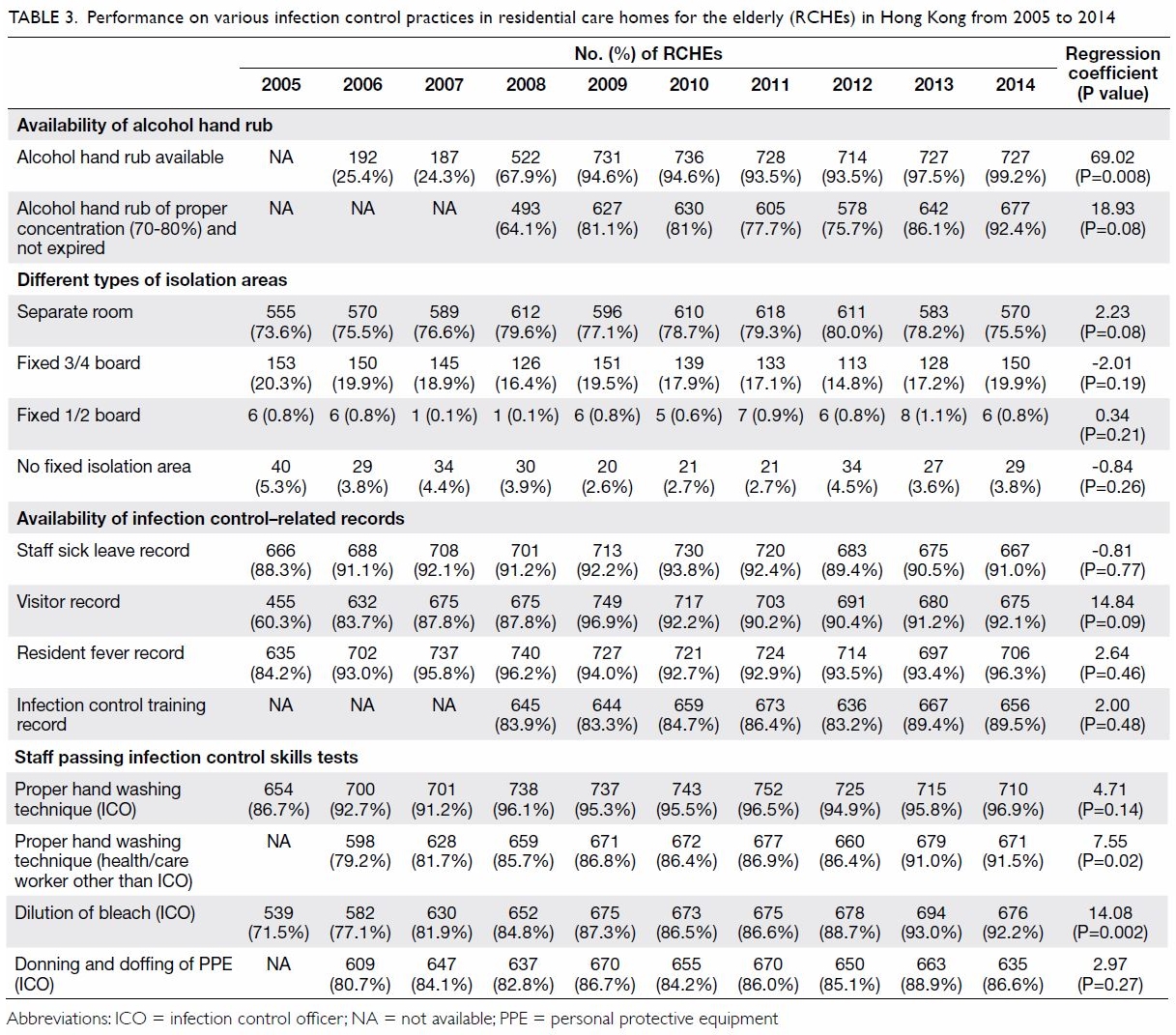

Part II: Infection control—environment and facilities

Common area

The RCHEs are collective living places where

communicable diseases can easily spread through contact with the

environment. Therefore, it is essential for RCHEs to be equipped with

proper facilities to prevent outbreaks. After years of promotion, the

proportion of RCHEs with alcohol hand rub increased significantly from

25.4% in 2006 to 99.2% in 2014 (P=0.008), as shown in Table

3. Nevertheless, further examination of a selected bottle of alcohol

hand rub at each of the RCHEs revealed that, in 2014, only 92.4% of RCHEs

had alcohol hand rub that had proper concentrations and were within the

expiry dates. Although this was an improvement from 64.1% in 2008, a

difference in performance was observed in 2014, with only 90.7% of private

RCHEs having proper alcohol hand rub, compared with 97.3% of non-private

RCHEs (P=0.003).

Table 3. Performance on various infection control practices in residential care homes for the elderly (RCHEs) in Hong Kong from 2005 to 2014

Isolation area

According to the COP for RCHEs,2 an isolation facility is a basic requirement for an

RCHE and is defined as “a designated area or room with good ventilation,

adequate space for equipment for proper disposal of personal and clinical

wastes, and basic hand hygiene and hand-drying facilities as well as

electric call bell.” The proportion of RCHEs equipped with a designated

room as an isolation area for fever cases ranged from 73.6% to 80.0%

between 2005 and 2014. No obvious trend was observed. In 2014, 19.9% and

0.8% of RCHEs were still only able to provide fixed boards of either

three-quarters or half the height of the room, respectively, as partitions

for the isolation area instead of providing separate rooms (Table

3). More non-private than private RCHEs were able to designate a

separate room for isolation in 2014 (90.3% vs 73.3%, P<0.05). However,

of the rooms designated as isolation areas, 1.5% in non-private RCHEs and

5.3% in private RCHEs were found to be occupied by residents without the

need for isolation, or used for storage.

Part III: Health monitoring and record keeping in

residential care homes for the elderly

For contact tracing and outbreak investigation, a

proper record system is essential. Only 60.3% of all RCHEs kept proper

visitors’ record in 2005, increasing to 92.1% in 2014. There were also

moderate improvements in the maintenance of sick leave records for staff,

fever records for residents, and training records on infection control for

staff, as shown in Table 3. However, a statistically significant trend

could not be identified.

Part IV: Infection control skills and practice

The ICO’s skill at hand washing, wearing and

removing of personal protective equipment, and preparing bleach solution

for environmental disinfection were tested in each RCHE. In addition to

assessing the ICO, a health worker or care worker was also selected at

random for hand washing technique auditing. The proportion of ICOs with

proper hand washing technique increased from 86.7% in 2005 to 96.9% in

2014, although a statistically significant trend was not observed

(P=0.14). However, an improvement trend was observed for non-ICO

health/care workers from 79.2% in 2006 to 91.5% in 2014 (P=0.02) [Table

3]. The proportion of ICOs with proper skills on wearing and

removing of personal protective equipment ranged from 80.7% to 88.9%

between years 2006 and 2014 (P=0.27). The proportion of ICOs who were able

to prepare bleach solution with the proper concentration showed an

improving trend from 71.5% in 2005 to 92.2% in 2014 (P=0.002).

Discussion

Infectious disease outbreaks are major concerns for

RCHEs as they often lead to significant morbidity and mortality. Local

data on infection control practices among RCHEs are limited. The current

study is the first institution-based serial survey on the trend of

infection control practices among RCHEs.

Residents of RCHEs are often functionally impaired,

putting them at higher risk of infection.10

Our results show that the proportion of RCHE residents aged ≥85 years is

increasing (Fig). This is expected to result in increased

prevalence of co-morbidities and functional impairment, leading to further

infection control challenges.

There have been improvements in infection control

practices among RCHEs over the study period from 2005 to 2014, in terms of

manpower, facilities, practices, knowledge, and skills. The improvement

was most obvious in terms of manpower and facilities. More nurses and

health workers were recruited into RCHEs, and common areas equipped with

alcohol hand rub. There was also a 10.2% improvement in hand washing

skills and a 5.9% improvement on skills of wearing and removing of

personal protective equipment among ICOs during the study period (Table

3). Possible contributory factors to such improvements may include

the overall increased level of awareness on the importance of infection

control, increased availability of manpower11

12 13

and financial resources, and improved access to infection control training

programmes.

Despite the improvements in infection control,

there are some areas of concern that are worth noting.

First, there was a sharp initial increase in the

number of RCHEs that had separate rooms as isolation areas in 2004. This

was likely an enhancement measure in response to the SARS outbreak in

2003. However, the proportion of RCHEs with separate isolation rooms has

remained stable at around 70% since then, despite ongoing training and

education. Possible explanations for this plateau include lack of space,

other competing demands, and other resourcing issues.

A similar plateau effect was also observed for

knowledge and skills on infection control measures. The RCHE staff’s

knowledge on the assessment items significantly improved (to near 90% for

most topics), then showed little further improvement.

Non-private RCHEs consistently performed better

than private RCHEs, especially in terms of nursing manpower, availability

of proper isolation areas, and availability of effective alcohol hand rub.

There is a fundamental funding difference between private and non-private

RCHEs. In addition to complying with statutory requirements, government

subvented RCHEs or those providing subsidised places (eg, RCHEs

participating in bought place schemes) are also required to meet quality

standards set out in the service contracts with the government. However,

private RCHEs not participating in such schemes are only required to

comply with the minimum statutory standards, such that service quality

among private RCHEs remains variable.14

Moreover, the high staff turnover rate in the

private sector may also explain why the performance of infection control

in private RCHEs still lags behind that of non-private RCHEs, because

knowledge and skills are not retained when trained care workers leave.15

There are several main limitations to our study.

First, although RCHE staff have attained a generally adequate level of

knowledge and skills on infection control, the implementation or the

extent of adoption of these skills in daily practice could not be

ascertained by our assessments which took the form of knowledge and skill

tests rather than covert observation of real practice. In addition, the

achieved results might not be representative, because the pre-scheduling

allowed ample lead time for the staff of the RCHEs to prepare for the

assessment. Unannounced visits and covert observation might provide a more

accurate assessment of staff skill levels and the extent of application of

such skills in daily practice, although covert observation itself may pose

other practical challenges.16

Second, it was not feasible for us to interview all

staff during our site visits, because the RCHEs must maintain routine

service for residents. During site visits, we assessed the knowledge and

practice of only the ICO and one additional health or care worker. The

performance of these two selected workers might not be representative of

all staff of the RCHE.

Third, to enhance comparability of assessment

results, most questions asked and skills tested were similar between

years. Thus, the assessment content might become predictable as the

assessments were repeated annually. This might have led to survey fatigue

and inability to capture true performance.

With an increasingly frail and ageing cohort of

residents, RCHEs are expected to face a growing risk of infectious disease

outbreaks in the coming decades, especially those involving

multidrug-resistant organisms. Other than general infection control

measures already adopted by the RCHEs, having a stable and well-trained

workforce will become an increasingly important factor in determining the

success of RCHEs in combating infectious diseases, especially as the

number of elderly residents with special care needs (such as those with

indwelling urinary catheters or on nasogastric feeding) is rising.

Manpower planning, development, and staff retention will remain a

challenge for infection control.

Moreover, as knowledge and skills on infection

control have stopped improving, training on infection control should

emphasise encouraging sustainability of vigilant practices. Measures

including self-auditing on infection control should be considered, to

encourage RCHE staff to monitor their own infection control performance on

a regular basis, between annual external assessments.

Conclusion

This is the first territory-wide report on trends

in infection control performance in RCHEs in Hong Kong. Data collected

enabled us to understand the strengths and limitations in RCHEs on

infection control, thus allowing stakeholders to design more targeted

infection control training programmes.

Knowledge and skills on infection control have

reached an adequate level and remained stable. Future infection control

training should aim to support sustained compliance with proper practice,

through introduction of elements such as self-audits.

Author contributions

All authors had full access to the data,

contributed to the study, approved the final version for publication, and

take responsibility for its accuracy and integrity.

Concept or design: GCY Wong, T Ng, T Li.

Acquisition of data: GCY Wong.

Analysis or interpretation of data: GCY Wong.

Drafting of the article: GCY Wong.

Critical revision for important intellectual content: T Ng, T Li.

Acquisition of data: GCY Wong.

Analysis or interpretation of data: GCY Wong.

Drafting of the article: GCY Wong.

Critical revision for important intellectual content: T Ng, T Li.

Conflicts of interest

The authors have disclosed no conflict of interest.

Funding/support

The report was funded by the Department of Health,

Hong Kong.

Ethics approval

A waiver for ethical review was endorsed by the

Ethics Committee of the Department of Health, Hong Kong.

References

1. Census and Statistics Department, Hong

Kong SAR Government. 2016 Population By-census. Thematic report: older

persons. Available from:

https://www.bycensus2016.gov.hk/data/16BC_Older_persons_report.pdf.

Accessed 8 Jan 2019.

2. Social Welfare Department, Hong Kong SAR

Government. Code of practice for residential care homes (elderly persons).

Available from:

http://www.swd.gov.hk/doc/LORCHE/CodeofPractice_E_201303_20150313R3.pdf.

Accessed 8 Jan 2019.

3. Department of Health, Hong Kong SAR

Government. Guidelines on prevention of communicable diseases in

residential care home for the elderly (3rd edition). Available from:

https://www.chp.gov.hk/files/pdf/guidelines_on_prevention_of_communicable_diseases_in_rche_eng.pdf.

Accessed 8 Jan 2019.

4. Social Welfare Department, Hong Kong SAR

Government. List of residential care homes. Available from:

https://www.swd.gov.hk/en/index/site_pubsvc/page_elderly/sub_residentia/id_listofresi/.

Accessed 8 Jan 2019.

5. World Health Organization. WHO

guidelines on hand hygiene in health care. Available from:

http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/44102/9789241597906_eng.pdf?sequence=1.

Accessed 8 Jan 2019.

6. Audit tools for monitoring infection

control guidelines within the community setting. Bathgate, UK: Infection

Control Nurses Association; 2005.

7. Routine practices and additional

precautions in all health care settings. Canada: Provincial Infectious

Diseases Advisory Committee. Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care; 2009.

8. von Elm E, Altman DG, Egger M, Pocock

SJ, Gøtzsche PC, Vandenbroucke JP; STROBE Initiative. The strengthening

the reporting of observational studies in epidemiology (STROBE) statement:

guidelines for reporting observational studies. PLoS Med 2007;4:e296. Crossref

9. Social Welfare Department, Hong Kong SAR

Government. SWD elderly information website. Type of residential care

homes. Available from:

https://www.elderlyinfo.swd.gov.hk/en/rches_natures.html. Accessed 8 Jan

2019.

10. Büla CJ, Ghilardi G, Wietlisbach V,

Petignat C, Francioli P. Infections and functional impairment in nursing

home residents: a reciprocal relationship. J Am Geriatr Soc 2004;52:700-6.

Crossref

11. Castle NG, Engberg J. The influence of

staffing characteristics on quality of care in nursing homes. Health Serv

Res 2007;42:1822-47. Crossref

12. Bostick JE, Rantz MJ, Flesner MK,

Riggs CJ. Systematic review of studies of staffing and quality in nursing

homes. J Am Med Dir Assoc 2006;7:366-76. Crossref

13. Bowers BJ, Esmond S, Jacobson N. The

relationship between staffing and quality in long-term care: exploring the

views of nurse aides. J Nurs Care Qual 2000;14:55-64. Crossref

14. Hong Kong SAR Government’s response to

a question raised by a Legislative Councillor on 11 January 2017.

Available from:

https://www.info.gov.hk/gia/general/201701/11/P2017011100501.htm. Accessed

28 Jan 2019.

15. Research Brief Issue No. 1 2015-2016,

Research Office, Legislative Council Secretariat, Hong Kong. Available

from:

https://www.legco.gov.hk/research-publications/english/1516rb01-challenges-of-population-ageing-20151215-e.pdf.

Accessed 8 Jan 2019.

16. Petticrew M, Semple S, Hilton S, et

al. Covert observation in practice: Lessons from the evaluation of the

prohibition of smoking in public places in Scotland. BMC Public Health

2007;7:204. Crossref