Hong

Kong Med J 2018 Aug;24(4):400–7 | Epub 27 Jul 2018

DOI: 10.12809/hkmj177141

© Hong Kong Academy of Medicine. CC BY-NC-ND 4.0

REVIEW ARTICLE

Mixed methods study on elimination of tuberculosis in

Hong Kong

Greta Tam, MB, BS, MS; H Yang, MPH; Tammy Meyers,

MB, BS, PhD

Jockey Club School of Public Health and Primary

Care, The Chinese University of Hong Kong, Shatin, Hong Kong

Corresponding author: Prof Greta Tam (gretatam@cuhk.edu.hk)

Abstract

Introduction: Tuberculosis

(TB) commonly affects developing countries. Several developed regions in

Asian still have a stagnant intermediate TB burden. Information to

adequately inform TB strategies is lacking. We conducted a mixed methods

study to fill this information gap in Hong Kong.

Methods: Data from the Hong Kong

government were used to analyse trends of TB notification rates compared

with World Health Organization (WHO) targets. A review of policy

documents and literature was conducted to evaluate TB control and

elimination in Hong Kong.

Results: Extrapolated trends

showed that Hong Kong will be unable to meet the WHO target of a 90%

drop in incidence rate by 2030. The policy review showed that the Hong

Kong government has not set a clear strategy and timeline for specific

goals in TB control and elimination. The literature review found that

older adults are largely responsible for the stagnant TB prevalence

because of reactivation of latent TB infection, while mortality

of hospitalised patients with TB is still high because of delayed

diagnosis and treatment.

Conclusion: Tuberculosis

incidence is currently under control in Hong Kong, but further actions

are needed if the elimination targets are to be achieved. Improved

diagnostic tools are required, and policies targeting latent TB infection in older

adults should be implemented to achieve the WHO target by 2030.

Introduction

Tuberculosis (TB) is a major global health burden

that ranks with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)/acquired immune

deficiency syndrome (AIDS) as a leading cause of death worldwide. The

World Health Organization (WHO) estimated that 9.6 million people were

sickened by TB and 1.5 million died as a result in 2014, with 58% of

global TB cases occurring in the South-East Asia and Western Pacific

regions.1 2 As a part of the global response to TB, the sixth

Millennium Development Goal (MDG) set out to halve TB prevalence and

mortality rates by 2015 compared with the 1990 baseline.3 Following significant declines in TB mortality and

prevalence rates, in 2015, the third Sustainable Development Goals

contained targets to end the epidemics of AIDS, TB, malaria, and neglected

tropical disease by 2030.4 The TB

target for 2030 is to reduce the number of TB deaths by 90% compared with

2015 numbers. The WHO established the End TB Strategy in 2014, aiming to

reduce the TB burden by 2030 and eliminate TB entirely by 2050.5 6 Advanced

economies such as the US and Australia7

typically have low TB incidence, and TB is commonly known as a disease of

poverty that more heavily affects developing countries.8 The Global Fund is conducting country case studies on

HIV/AIDS, TB, and malaria in several developing countries, including

Haiti, Pakistan, and the Philippines.9

No country case studies have yet been conducted in developed Asian

countries/regions such as Hong Kong, Japan, Singapore, Taiwan, or South

Korea, which have good health infrastructure and stable economic growth,

but where intermediate levels of TB incidence persist.10 11

Reaching the WHO targets in Asia will require

strategies specific to TB epidemiology in this setting. However,

information to adequately inform strategies is lacking. The last report of

comparative data between Asian countries was published 10 years ago by the

WHO.5 The reasons for the gap

between the TB burden in Asian countries and that in their equally

developed counterparts in other regions need to be understood. The TB

burden in low-incidence countries is attributable mostly to immigrants.12 In contrast, the stagnant

intermediate incidence in developed Asian countries is ascribed mainly to

latent TB infection in ageing populations.13

Compared with that of Singapore, Japan, or Western

countries with similar gross domestic products, the notification rate of

TB in Hong Kong is relatively high (60 per 100 000 population in 2016).11 14

Presently, TB is the second most common notifiable disease in Hong Kong,

following chickenpox.15 The TB

notification rate in Hong Kong has declined slowly since 1995, although

the notification rate only dropped below 100 per 100 000 population in 2002,

and it took until 2011 for the notification rate to decline below 70 per

100 000 population.16

The present case study of the TB situation in Hong

Kong highlights successful policies intended to achieve WHO goals and

identifies areas for further research or intervention in gaps that could

prevent attainment of these targets. This could facilitate useful

comparisons with the situation in other developed Asian countries.

Methods

Secondary data analysis of publicly available data

A document review including both policy and

literature was conducted. Statistics on TB notification in Hong Kong were

obtained from the official website of the Tuberculosis and Chest Service,

Department of Health of Hong Kong SAR Government.14

The TB notification rates were analysed in terms of immigrant status,

age-group, and gender and presented in line graphs. The notification trend

was extrapolated to 2030 by using Microsoft Excel’s FORECAST function on

the trend in the past 10 years (2005-2015).

Policy review

Existing documents from the Tuberculosis and Chest

Service, Department of Health of Hong Kong SAR Government, such as the TB

manual (2006),17 TB annual reports

(2007-2013),18 19 20 21 22 23 24

information and guidelines (2006-2015),25

26 27

28 29

30 31

and other recommendations were obtained. Reports and strategies regarding

TB control and elimination from the WHO were also reviewed to analyse how

the strategy had been operationalised, how this may affect implementation

of local programmes, and to identify the policy gap between the Hong Kong

government’s and WHO’s strategies.

Literature review

Two electronic databases, PubMed and Google

Scholar, were searched to identify articles related to TB control and

elimination in Hong Kong. The key words ‘tuberculosis’ or ‘TB’ in

combination with the terms ‘Hong Kong’, ‘epidemiology’, ‘risk factors’,

‘prevention’, ‘treatment’, ‘Latent TB’, ‘MDR-TB’, or ‘XDR-TB’ were used to

search for relevant articles.

Selected publications included studies (a) carried

out in Hong Kong; (b) published in the past 10 years; (c) related to TB

prevalence, at-risk populations, and TB control measures/interventions in

Hong Kong; (d) with full-text articles in English; (e) with no overlapping

data; and (f) qualitative studies with sufficient sample size, significant

results (P<0.05), and specified outcomes/outputs.

Results

Tuberculosis notification in Hong Kong

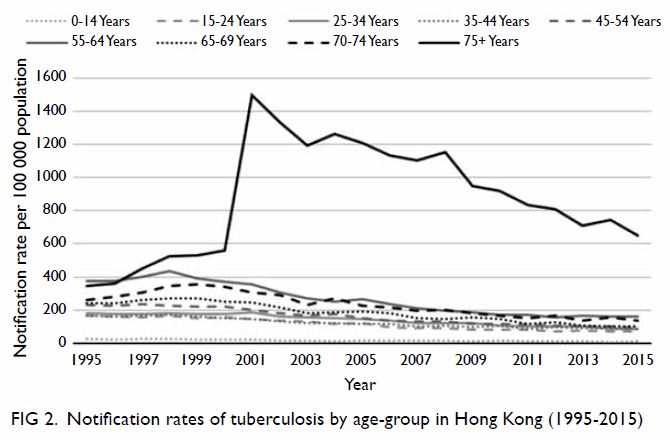

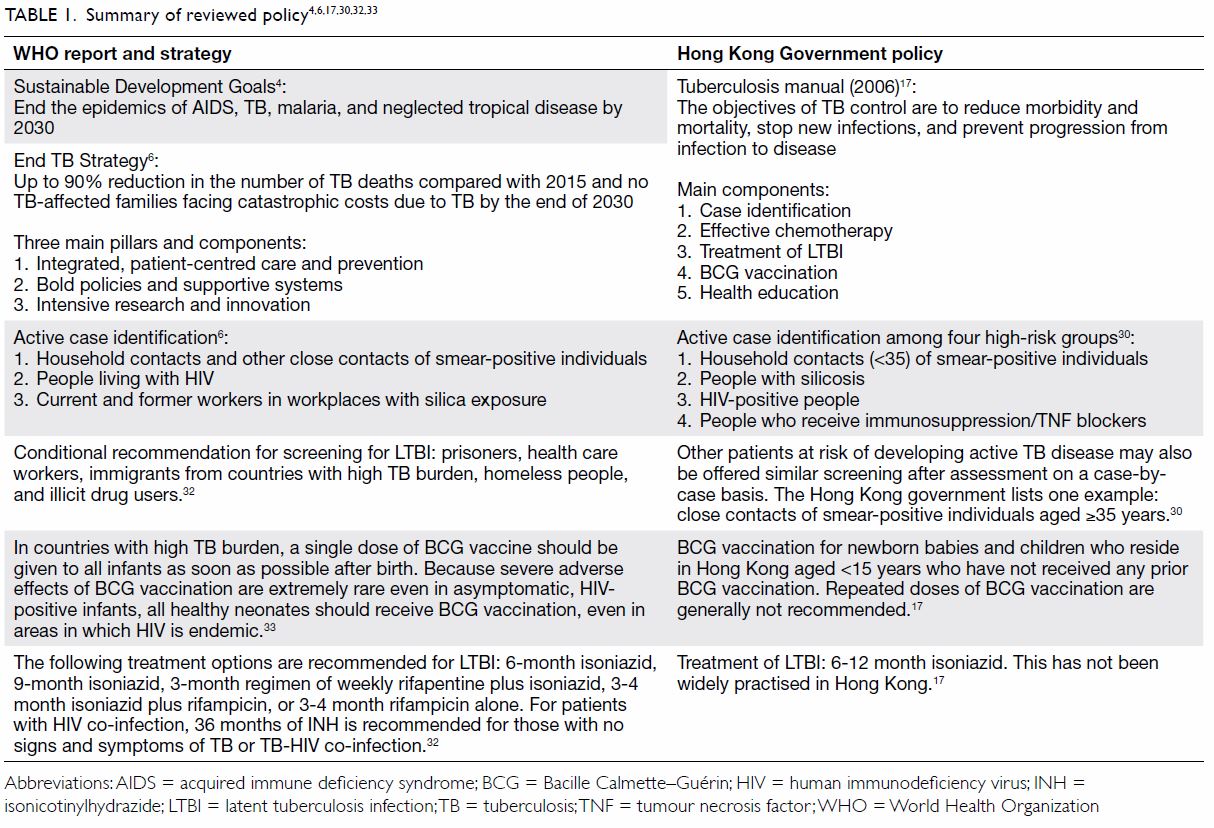

Since 1947, a downward trend in total TB

notification in Hong Kong has been observed. From 1970 to 1977, TB

notification rapidly declined but remained stagnant thereafter (Fig

1). The oldest age-group (≥75 years) had much higher TB notification

rates (Fig 2). Between 1995 and 2015, reductions in

notification rates occurred in younger age-groups but increased sharply at

the turn of the millennium in the oldest group, whose notification rate

had only gradually decreased by 2015. Notification rates in both genders

showed downward trends, although men had a higher notification rate than

women (data not shown).

Figure 1. Notification rates of TB in Hong Kong (1947-2015) with extrapolated trend to 2030 and estimated trend according to the WHO target

Tuberculosis notification rates dropped rapidly

after the Bacille Calmette–Guérin (BCG) vaccine was introduced in 1952,

with a further decline after the introduction of directly observed

treatment short course (DOTS) [Fig 1]. The incidence in 2015 had almost halved

compared with that in 1990. Extrapolated trends showed that at the current

rate, Hong Kong would be unable to meet the WHO target of a 90% drop in

incidence rate by 2030. By then, Hong Kong’s TB notification rate is

predicted to drop by only 60.2%, compared with that in 2015. The analysis

shows that Hong Kong could become a low-incidence country (10 cases per

100 000 population) by 2036.

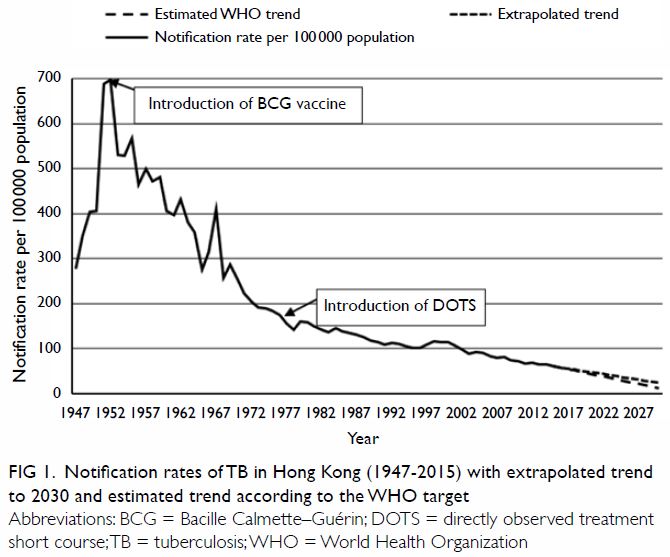

Comparison of reviewed policy between the World Health

Organization and Hong Kong

A comparison between the WHO’s and Hong Kong’s TB

policies is shown in Table 1.4 6 17

30 32

33 In 2015, the Sustainable

Development Goal 3 included a target to end the TB epidemic by 2030,4 and the End TB Strategy aims to achieve a 90% drop in

TB incidence rate and up to 95% reduction in number of TB-related deaths

by 2035 compared with those in 2015.6

Yet, the Hong Kong government has not set a clear strategy and timeline

for specific goals in TB control and elimination.

The WHO guidelines for management of latent TB

infection (LTBI) strongly recommended that high-income and upper-middle

income countries with TB incidence less than 100 per 100 000 population

per year perform systematic testing and treatment of LTBI in specific

groups, and Hong Kong was listed among these.32

Hong Kong follows the WHO recommendations for LTBI screening in high-risk

groups. However, conditional recommendations for a number of target

populations to be included in active case finding are not included in the

local Hong Kong policy documents. According to the Hong Kong TB Manual,

active case finding in high-risk groups was not very effective, as only 1%

of active TB was found in household contacts in 2004.17

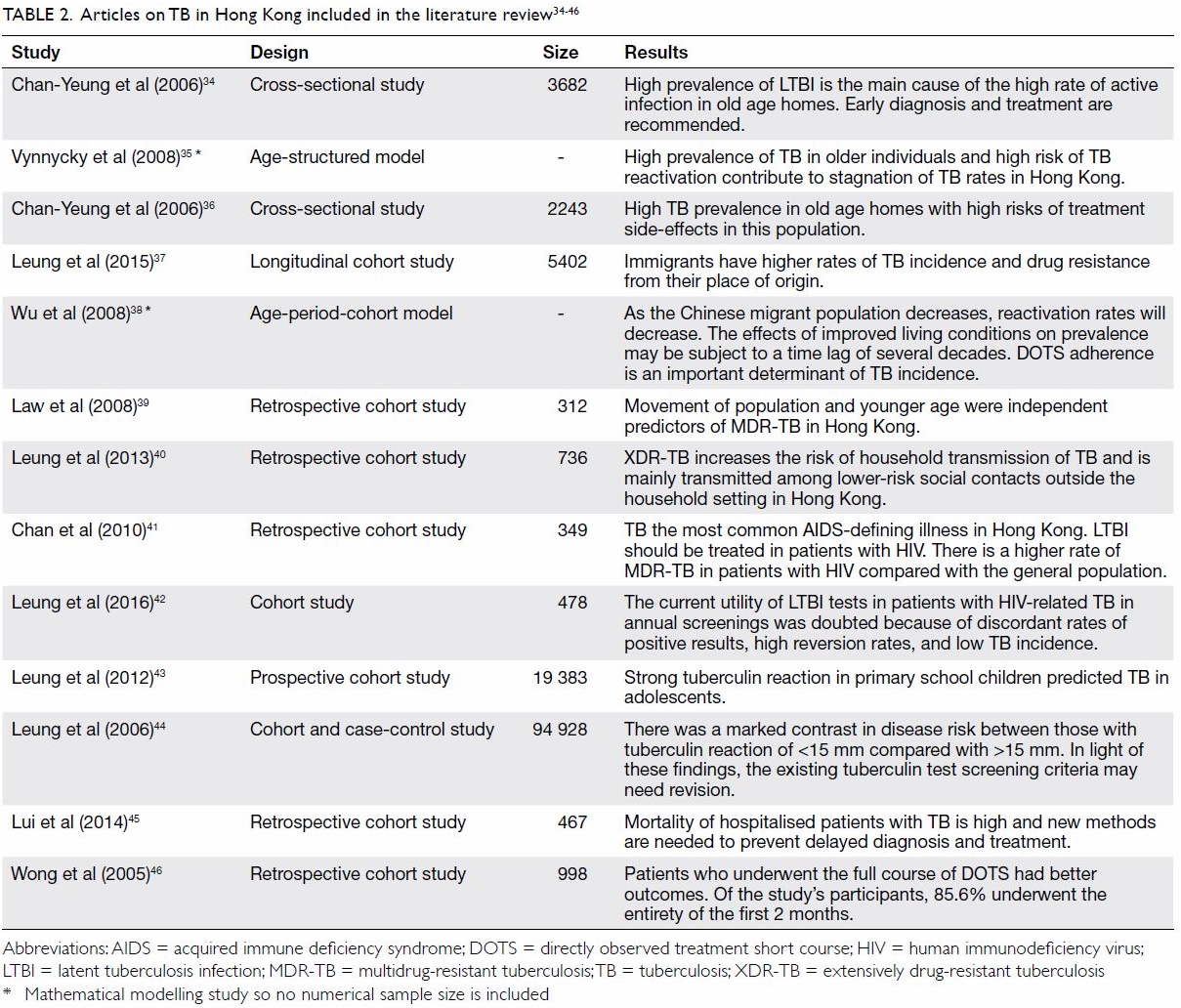

Summary of reviewed literature

We reviewed the TB literature about studies

conducted in Hong Kong published in the past 10 years (Table

2).34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 45 46 Thirteen

published studies were included: two on older adults in old age homes, one

on migrant populations, two on drug-resistant TB, two on HIV-related TB,

two on primary school children, three on TB treatment outcomes, and one on

TB prevalence in Hong Kong.

Table 2. Articles on TB in Hong Kong included in the literature review34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 45 46

Among the included studies, three indicated that

Hong Kong’s TB prevalence rate is stagnating because of high TB prevalence

in older adults and a high risk of TB reactivation34 35 caused by

high prevalence of latent infection among older adults in old age homes.36 Some immigrants come from

countries with higher TB incidence and drug resistance rates, particularly

mainland China. These migrants may also be at increased risk of TB

reactivation.37 However, TB in the

migrant population is likely to decrease as migration from China is

reduced and living conditions for those entering the city improve.38

Multidrug-resistant TB (MDR-TB) is a threat that is

more likely in patients diagnosed with TB at younger ages.39 Extensively drug-resistant TB (XDR-TB) significantly

increases household TB transmission, demonstrating a need for prolonged

household surveillance.40

Treatment of LTBI is recommended to control TB, especially among people

with HIV. Two studies reported outcomes of treating LTBI in patients with

HIV in Hong Kong, one confirming the usefulness of LTBI treatment,41 while the other doubted the utility of LTBI tests in

annual screening of patients with HIV because of discordant results

between different tests.42

Identification of children with LTBI is also useful: in a study that

described the use of tuberculin tests to screen primary school children,

strong tuberculin reactions (>15 mm) predicted TB in adolescence.43 44 Diagnosis

of TB is still problematic, and new methods are needed to prevent delayed

diagnosis and treatment,35 as

mortality of hospitalised TB patients is still high.45 However, one Hong Kong study demonstrated that

although early diagnosis and treatment are recommended, TB therapy carried

a high risk of side-effects in the study population.36 Directly observed treatment short course has

significantly decreased TB incidence,38

46 although not all patients in

Hong Kong completed the first 2 months of treatment, with failure to

complete treatment predicting poorer outcomes than undergoing the full

course.46

Discussion

In Hong Kong’s older adult population, TB accounts

for the majority of the city’s high burden from the disease. In Hong Kong,

those aged >75 years showed an especially high TB incidence rate.

Migrants and people with HIV also have higher TB prevalence but contribute

significantly less to the burden than do older adults. Children with a

strong purified protein derivative reaction indicating infection were more

prone to develop TB in adolescence. Also, MDR-TB and XDR-TB pose a

relatively rare but important threat in Hong Kong. Late or underdiagnosis

results in high TB-related mortality in those who present symptoms late

and require hospitalisation.

High rates of LTBI in Hong Kong have been

documented in other Asian countries with low and intermediate TB burden.47 The BCG vaccine was introduced

to Hong Kong in April 195217;

therefore, by 1995, 2005 and 2015, those aged >43, >53 and >63

years, respectively, would not have been vaccinated in infancy. The higher

prevalence of LTBI and active TB in old age homes compared with that in

older adults living in the community is a trend shared with other

countries, including low-burden countries such as the US.48 49 50 Despite the higher prevalence of LTBI in

institutionalised older adults in Hong Kong (68.6%)36 compared with their American counterparts (5.5%),51 52 53 54 55 56 Hong Kong

has not followed the US policy of LTBI testing in this population.57 Further research is needed to explore the feasibility

and cost-effectiveness of screening and providing prophylaxis to older

adults and other populations.

In contrast to countries with low TB burden, where

infections in migrants primarily contribute to the burden,58 the infection rate in Hong Kong’s migrant population

is declining.16 However, MDR-TB

rates are higher in migrants and younger age-groups in Hong Kong and

countries with low TB burden.59 60 A systematic review also

concurred with a Hong Kong study’s findings that patients with HIV had a

higher risk of MDR-TB.41 61 Meanwhile, the findings on transmission of XDR-TB in

Hong Kong differ from those in Peru, where household contacts reported a

very high prevalence of XDR-TB.62

It has been postulated that in Hong Kong, XDR-TB is mainly transmitted

outside the household setting because of the high population density.40 The Peru study’s different findings may support this

idea, as the population density of Hong Kong is more than double that of

Lima.63 64

The WHO has called for improved tests to diagnose

LTBI, as the current ones lack accuracy.65

This was echoed by findings in the study of patients with HIV by Leung et

al.42 The finding that a strong

tuberculin reaction in 6-to-10-year-old schoolchildren in Hong Kong

predicted TB in adolescence was reinforced by a similar study in

Singapore, which is also a developed city with an intermediate TB burden.43 66

67 However, Hong Kong

schoolchildren are not routinely screened for LTBI.30 It may be advisable to extend LTBI testing to cover

schoolchildren.

The high mortality of hospitalised patients with TB

in Hong Kong is also seen in many other countries,45 68

emphasising the need for early detection and treatment. The DOTS strategy

is an important cornerstone of TB treatment; however, there is room for

improvement in compliance with DOTS in Hong Kong.46

Other developed Asian countries have similar DOTS treatment success rates

to Hong Kong.69 Without

improvement in medication adherence, treatment success rates are unlikely

to rise.

Policy recommendations

Hong Kong reached the MDG target of reducing TB

incidence, with a declining notification rate. However, according to the

extrapolated trend, if improvements are not instituted, there will likely

be only a 60% reduction in TB notification by 2030 compared with the 2015

baseline. To achieve the goal of 80% reduction in TB incidence proposed by

the End TB Strategy,70 an improved

supportive protocol targeting older adults with a clear timeline is

needed. In addition, the Hong Kong government should consider screening

high-risk groups included in the WHO’s conditional recommendations. More

research needs to be done to explore whether screening these groups would

be beneficial.

Limitations

This study has several limitations. First, some key

literature and important policies or strategies may have been missed, as

no systematic review was conducted. This may have imposed error on the

screening and article selection. Second, some patients that did not seek

health care may have been missed by the system. Despite these limitations,

this research has provided helpful suggestions and valuable insights for

future research and implementation of TB-related policy.

Conclusion

The TB incidence rate is currently under control in

Hong Kong, but further actions are warranted if the elimination targets

are to be achieved. More accurate diagnostic tools are required, and

policies targeting LTBI in older adults and children should be implemented

to achieve the WHO goal by 2030.

Author contributions

Concept or design: G Tam.

Acquisition of data: H Yang.

Analysis or interpretation of data: H Yang.

Drafting of the article: All authors.

Critical revision for important intellectual content: G Tam, T Meyers.

Acquisition of data: H Yang.

Analysis or interpretation of data: H Yang.

Drafting of the article: All authors.

Critical revision for important intellectual content: G Tam, T Meyers.

Funding/support

This research received no specific grant from any

funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Declaration

All authors have disclosed no conflicts of

interest. All authors had full access to the data, contributed to the

study, approved the final version for publication, and take responsibility

for its accuracy and integrity. Abstract of this article was presented at

Infection 2016 (13th Annual Scientific Meeting), 22 June 2016, The Chinese

University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong.

References

1. World Health Organization. Tuberculosis,

Fact sheet N104. Available from:

http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs104/en/. Accessed 11 Jul 2018.

2. World Health Organization. Global

tuberculosis report 2015. Available from:

http://www.who.int/tb/publications/global_report/gtbr15_main_text.pdf.

Accessed 11 Jul 2018.

3. World Health Organization. Global

tuberculosis report 2014. Available from:

http://www.who.int/tb/publications/global_report/gtbr14_main_text.pdf.

Accessed 11 Jul 2018.

4. World Health Organization. Health in

2015: from MDGs to SDGs. WHO report 2015. Available from:

http://www.who.int/gho/publications/mdgs-sdgs/en/. Accessed 11 Jul 2018.

5. World Health Organization. Framework

towards TB elimination in low-incidence countries. 2014. Available from:

http://www.who.int/tb/publications/Towards_TB_Eliminationfactsheet.pdf.

Accessed 11 Jul 2018.

6. World Health Organization. The End TB

strategy; global strategy and targets for tuberculosis prevention, care

and control after 2015. 2016. Available from:

http://www.who.int/tb/post2015_TBstrategy.pdf. Accessed 11 Jul 2018.

7. International Monetary Fund. World

economic outlook: adjusting to lower commodity prices. 2015. Available

from: http://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/weo/2015/02/pdf/text.pdf.

Accessed 11 Jul 2018.

8. World Health Organization. Addressing

poverty in TB control. Options for national TB control programmes.

Available from:

http://www.who.int/tb/areas-of-work/population-groups/poverty/en/ Accessed

11 Jul 2018.

9. The Global Fund. Where we invest, The

Global Fund. Available from: http://www.theglobalfund.org/en/overview/.

Accessed 11 Jul 2018.

10. The World Bank. Incidence of

tuberculosis (per 100,000 people). Available from:

http://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SH.TBS.INCD. Accessed 11 Jul 2018.

11. World Health Organization.

Tuberculosis (TB), tuberculosis country profiles. Available from:

http://www.who.int/tb/country/data/profiles/en/. Accessed 11 Jul 2018.

12. Pareek M, Abubakar I, White PJ,

Garnett GP, Lalvani A. Tuberculosis screening of migrants to low-burden

nations: insights from evaluation of UK practice. Eur Respir J

2011;37:1175-82. Crossref

13. World Health Organization.

Tuberculosis control in the South-East Asia and Western Pacific regions

2005: a biregional report. Available from:

http://iris.wpro.who.int/bitstream/handle/10665.1/5519/9290611960_eng.pdf.Accessed

11 Jul 2018.

14. Tuberculosis and Chest Service,

Department of Health, Hong Kong SAR Government. Statistics on

tuberculosis, 2015. Available from:

http://www.info.gov.hk/tb_chest/index_2.htm. Accessed 11 Jul 2018.

15. Centre for Health Protection,

Department of Health, Hong Kong SAR Government. Number of notifiable

infectious disease by month in 2015, notifiable infectious disease,

Statistics on communicable diseases. Available from:

http://www.chp.gov.hk/en/data/1/10/26/43/3829.html. Accessed 11 Jul 2018.

16. Centre for Health Protection,

Department of Health, Hong Kong SAR Government. Notification and death

rate of tuberculosis (all forms), 1947-2015. Available from:

http://www.chp.gov.hk/en/data/4/10/26/43/88.html. Accessed 11 Jul 2018.

17. Tuberculosis and Chest Service,

Department of Health, Hong Kong SAR Government. Tuberculosis manual 2006.

2006. Available from:

http://www.info.gov.hk/tb_chest/doc/Tuberculosis_Manual2006.pdf. Accessed

11 Jul 2018.

18. Tuberculosis and Chest Service,

Department of Health, Hong Kong SAR Government. Annual report 2007. 2007.

Available from: http://www.info.gov.hk/tb_chest/doc/Annual Report

2007.pdf. Accessed 11 Jul 2018.

19. Tuberculosis and Chest Service,

Department of Health, Hong Kong SAR Government. Annual report 2008. 2008.

Available from:

http://www.info.gov.hk/tb_chest/doc/Annual_Report_2008.pdf. Accessed 11

Jul 2018.

20. Tuberculosis and Chest Service,

Department of Health, Hong Kong SAR Government. Annual report 2009. 2009.

Available from: http://www.info.gov.hk/tb_chest/doc/AnnualReport2009.pdf.

Accessed 11 Jul 2018.

21. Tuberculosis and Chest Service,

Department of Health, Hong Kong SAR Government. Annual report 2010. 2010.

Available from: http://www.info.gov.hk/tb_chest/doc/AnnualReport2010.pdf.

Accessed 11 Jul 2018.

22. Tuberculosis and Chest Service,

Department of Health, Hong Kong SAR Government. Annual report 2011. 2011.

Available from: http://www.info.gov.hk/tb_chest/doc/AnnualReport2011.pdf.

Accessed 11 Jul 2018.

23. Tuberculosis and Chest Service,

Department of Health, Hong Kong SAR Government. Annual report 2012. 2012.

Available from: http://www.info.gov.hk/tb_chest/doc/AnnualReport2012.pdf.

Accessed 11 Jul 2018.

24. Tuberculosis and Chest Service,

Department of Health, Hong Kong SAR Government. Annual report 2013. 2013.

Available from: http://www.info.gov.hk/tb_chest/doc/AnnualReport2013.pdf.

Accessed 11 Jul 2018.

25. Tuberculosis and Chest Service,

Department of Health, Hong Kong SAR Government. Recommendations on the

management of human immunodeficiency virus and tuberculosis coinfection.

2008. Available from:

http://www.chp.gov.hk/files/pdf/recommendations_on_management_of_human_immunodeficiency_virus_and_tuberculosis_coinfection_r.pdf.

Accessed 11 Jul 2018.

26. Tuberculosis and Chest Service,

Department of Health, Hong Kong SAR Government. Guidelines on the

management of multidrug-resistant and extensively drugresistant

tuberculosis in Hong Kong. 2008. Available from:

http://www.info.gov.hk/tb_chest/doc/MDRTBguideline_0812.pdf. Accessed 11

Jul 2018.

27. Centre for Health Protection,

Department of Health, Hong Kong SAR Government. The use of BCG vaccine in

HIV infected patients. 2009. Available from:

http://www.chp.gov.hk/files/pdf/the_use_of_bcg_vaccine_in_hiv_infected_patients_r.pdf.

Accessed 11 Jul 2018

28. Tuberculosis and Chest Service,

Department of Health, Hong Kong SAR Government. Ambulatory treatment and

public health measures for a patient with uncomplicated pulmonary

tuberculosis—an information paper. 2013. Available from:

http://www.info.gov.hk/tb_chest/doc/Information_paper_ambulatory_tb_2013.pdf.

Accessed 11 Jul 2018.

29. Tuberculosis and Chest Service,

Department of Health, Hong Kong SAR Government. Guidance on logistical

arrangement for targeted screening and treatment of latent tuberculosis

infection among immunocompetent household contacts of smear-positive

pulmonary tuberculosis patients in TB and Chest Service. 2013. Available

from:

http://www.info.gov.hk/tb_chest/doc/Guidance_Notes_Contact_TBCS_upated 1

NOV 2013.pdf. Accessed 11 Jul 2018.

30. Tuberculosis and Chest Service,

Department of Health, Hong Kong SAR Government. Guidelines on targeted

tuberculin testing and treatment of latent tuberculosis infection. 2015.

Available from:

http://www.info.gov.hk/tb_chest/doc/LTBI_guide_TBCS_2012_update 1

Nov2013_ADD_31March2015.pdf. Accessed 11 Jul 2018.

31. Tuberculosis and Chest Service,

Department of Health, Hong Kong SAR Government. Scheme for investigation

of close contacts (household) in the Tuberculosis & Chest Service,

Department of Health. 2015. Available from:

http://www.info.gov.hk/tb_chest/doc/TST_contacts of smear-negative

sources.pdf. Accessed 11 Jul 2018.

32. Getahun H, Matteelli A, Abubakar I, et

al. Management of latent mycobacterium tuberculosis infection: WHO

guidelines for low tuberculosis burden countries. Eur Respir J

2015;46:1563-76. Crossref

33. World Health Organization. Weekly

epidemiological record. 2004. Available from:

http://www.who.int/wer/2004/en/wer7904.pdf?ua=1. Accessed 11 Jul 2018.

34. Chan-Yeung M, Cheung AH, Dai DL, et

al. Prevalence and determinants of positive tuberculin reactions of

residents in old age homes in Hong Kong. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis

2006;10:892-8.

35. Vynnycky E, Borgdorff MW, Leung CC,

Tam CM, Fine PE. Limited impact of tuberculosis control in Hong Kong:

attributable to high risks of reactivation disease. Epidemiol Infect

2008;136:943-52. Crossref

36. Chan-Yeung M, Chan FH, Cheung AH, et

al. Prevalence of tuberculous infection and active tuberculosis in old age

homes in Hong Kong. J Am Geriatr Soc 2006;54:1334-40. Crossref

37. Leung CC, Chan CK, Chang KC, et al.

Immigrants and tuberculosis in Hong Kong. Hong Kong Med J 2015;21:318-26.

Crossref

38. Wu P, Cowling BJ, Schooling CM, et al.

Age-period-cohort analysis of tuberculosis notifications in Hong Kong from

1961 to 2005. Thorax 2008;63:312-6. Crossref

39. Law WS, Yew WW, Chiu Leung C, et al.

Risk factors for multidrug-resistant tuberculosis in Hong Kong. Int J

Tuberc Lung Dis 2008;12:1065-70.

40. Leung EC, Leung CC, Kam KM, et al.

Transmission of multidrug-resistant and extensively drug-resistant

tuberculosis in a metropolitan city. Eur Respir J 2013;41:901-8. Crossref

41. Chan CK, Alvarez Bognar F, Wong KH, et

al. The epidemiology and clinical manifestations of human immunodeficiency

virus–associated tuberculosis in Hong Kong. Hong Kong Med J 2010;16:192-8.

42. Leung CC, Chan K, Yam WC, et al. Poor

agreement between diagnostic tests for latent tuberculosis infection among

HIV-infected persons in Hong Kong. Respirology 2016;21:1322-9. Crossref

43. Leung CC, Yew WW, Au KF, et al. A

strong tuberculin reaction in primary school children predicts

tuberculosis in adolescence. Pediatr Infect Dis J 2012;31:150-3. Crossref

44. Leung CC, Yew WW, Chang KC, et al.

Risk of active tuberculosis among schoolchildren in Hong Kong. Arch

Pediatr Adolesc Med 2006;160:247-51. Crossref

45. Lui G, Wong RY, Li F, et al. High

mortality in adults hospitalized for active tuberculosis in a low HIV

prevalence setting. PLoS One 2014;9:e92077. Crossref

46. Wong MY, Leung CC, Tam CM, Lee SN.

Directly observed treatment of tuberculosis in Hong Kong. Int J Tuberc

Lung Dis 2005;9:443-9.

47. Mori T, Leung CC. Tuberculosis in the

global aging population. Infect Dis Clin North Am 2010;24:751-68. Crossref

48. Stead WW, Dutt AK. Tuberculosis in

elderly persons. Annu Rev Med 1991;42:267-76. Crossref

49. Stead WW, Lofgren JP, Warren E, Thomas

C. Tuberculosis as an endemic and nosocomial infection among the elderly

in nursing homes. N Engl J Med 1985;312:1483-7.Crossref

50. Macarthur C, Enarson DA, Fanning EA,

Hessel PA, Newman S. Tuberculosis among institutionalized elderly in

Alberta, Canada. Int J Epidemiol 1992;21:1175-9. Crossref

51. Shea KM, Kammerer JS, Winston CA,

Navin TR, Horsburgh CR Jr. Estimated rate of reactivation of latent

tuberculosis infection in the United States, overall and by population

subgroup. Am J Epidemiol 2014;179:216-25. Crossref

52. Welty C, Burstin S, Muspratt S, Tager

IB. Epidemiology of tuberculous infection in a chronic care population. Am

Rev Respir Dis 1985;132:133-6.

53. Dorken E, Grzybowski S, Allen EA.

Significance of the tuberculin test in the elderly. Chest 1987;92:237-40.

Crossref

54. Stead WW, To T. The significance of

the tuberculin skin test in elderly persons. Ann Intern Med

1987;107:837-42. Crossref

55. Nisar M, Williams CS, Ashby D, Davies

PD. Tuberculin testing in residential homes for the elderly. Thorax

1993;48:1257-60. Crossref

56. Creditor MC, Smith EC, Gallai JB,

Baumann M, Nelson KE. Tuberculosis, tuberculin reactivity, and delayed

cutaneous hypersensitivity in nursing home residents. J Gerontol

1988;43:M97-100. Crossref

57. Centers for Disease Control and

Prevention. Latent tuberculosis infection: a guide for primary health care

providers. 2013. Available from:

http://www.cdc.gov/tb/publications/ltbi/targetedtesting.htm. Accessed 11

Jul 2018.

58. Pareek M, Greenaway C, Noori T, Munoz

J, Zenner D. The impact of migration on tuberculosis epidemiology and

control in high-income countries: a review. BMC Med 2016;14:48. Crossref

59. Hargreaves S, Lönnroth K, Nellums LB,

et al. Multidrugresistant tuberculosis and migration to Europe. Clin

Microbiol Infect 2017;23:141-6. Crossref

60. Faustini A, Hall AJ, Perucci CA. Risk

factors for multidrug resistant tuberculosis in Europe: a systematic

review. Thorax 2006;61:158-63.Crossref

61. Mesfin YM, Hailemariam D, Biadgilign

S, Kibret KT. Association between HIV/AIDS and multi-drug resistance

tuberculosis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One

2014;9:e82235. Crossref

62. Becerra MC, Appleton SC, Franke MF, et

al. Tuberculosis burden in households of patients with multidrug-resistant

and extensively drug-resistant tuberculosis: a retrospective cohort study.

Lancet 2011;377:147-52. Crossref

63. World population review. Lima

population 2017. 2018. Available from:

http://worldpopulationreview.com/worldcities/lima-population/. Accessed 11

Jul 2018.

64. World population review. Hong Kong

population 2017. 2018. Available from:

http://worldpopulationreview.com/countries/hong-kong-population/#.

Accessed 11 Jul 2018.

65. World Health Organization. WHO

guidelines on the management of latent tuberculosis infection launched

today. Available from: http://www.who.int/tb/features_archive/LTBI/en/.

Accessed 11 Jul 2018.

66. Chee CB, Soh CH, Boudville IC, Chor

SS, Wang YT. Interpretation of the tuberculin skin test in Mycobacterium

bovis BCG-vaccinated Singaporean schoolchildren. Am J Respir Crit Care Med

2001;164:958-61. Crossref

67. World Health Organization.

Tuberculosis. 2007. Available from:

http://www.wpro.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs_20060829/en/. Accessed

11 Jul 2018.

68. Waitt CJ, Squire SB. A systematic

review of risk factors for death in adults during and after tuberculosis

treatment. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis 2011;15:871-85. Crossref

69. Tam CM. The DOTS strategy in Hong

Kong. Med Bull 2006;11:3-4.

70. World Health Organization. The End TB

Strategy. Available from: http://www.who.int/tb/End_TB_brochure.pdf?ua=1.

Accessed 11 Jul 2018.