Hong Kong Med J 2018 Jun;24(3):238–44 | Epub 21 May 2018

DOI: 10.12809/hkmj177039

© Hong Kong Academy of Medicine. CC BY-NC-ND 4.0

ORIGINAL ARTICLE

Hypospadias surgery in children: improved service model

of enhanced recovery pathway and dedicated surgical team

YS Wong, FHKAM (Surgery); Kristine KY Pang, FHKAM

(Surgery); YH Tam, FHKAM (Surgery)

Division of Paediatric Surgery and Paediatric

Urology, Department of Surgery, Prince of Wales Hospital, The Chinese

University of Hong Kong, Shatin, Hong Kong

Corresponding author: Dr YH Tam (pyhtam@surgery.cuhk.edu.hk)

Abstract

Introduction: Children in Hong

Kong are generally hospitalised for 1 to 2 weeks after hypospadias

repairs. In July 2013, we introduced a new service model that featured

an enhanced recovery pathway and a dedicated surgical team responsible

for all perioperative services. In this study, we investigated the

outcomes of hypospadias repair after the introduction of the new service

model.

Methods: We conducted a

retrospective study on consecutive children who underwent primary

hypospadias repair from January 2006 to August 2016, comparing patients

under the old service with those under the new service. Outcome measures

included early morbidity, operative success, and completion of enhanced

recovery pathway.

Results: The old service and new

service cohorts comprised 176 and 126 cases, respectively. There was no

difference between the two cohorts in types of hypospadias and surgical

procedures performed. The median hospital stay was 2 days in the new

service cohort compared with 10 days in the old service cohort

(P<0.001). Patients experienced less early morbidity (5.6% vs 15.9%;

P=0.006) and had a lower operative failure rate (20.2% vs 44.2%;

P<0.001) under the new service than the old service. Multivariable

analysis revealed that the new service significantly reduced the odds of

early morbidity (odds ratio=0.35, 95% confidence interval=0.15-0.85;

P=0.02) and operative failure (odds ratio=0.32, 95% confidence

interval=0.17-0.59; P<0.001) in comparison with the old service. Of

the new service cohort, 111(88.1%) patients successfully completed the

enhanced recovery pathway.

Conclusions: The enhanced

recovery pathway can be implemented safely and effectively to primary

hypospadias repair. A dedicated surgical team may play an important role

in successful implementation of the enhanced recovery pathway and

optimisation of surgical outcomes.

New knowledge added by this study

- Children can be discharged early from hospital after primary hypospadias repairs, regardless of the severity of the hypospadias and the surgical techniques used.

- Improved operative success of hypospadias repair may be achieved by dedicated hypospadias surgeons.

- Primary hypospadias repair in children can be considered as short-stay surgery.

- Tertiary centres for hypospadias may consider concentration of hypospadias repairs among a few dedicated surgeons.

Introduction

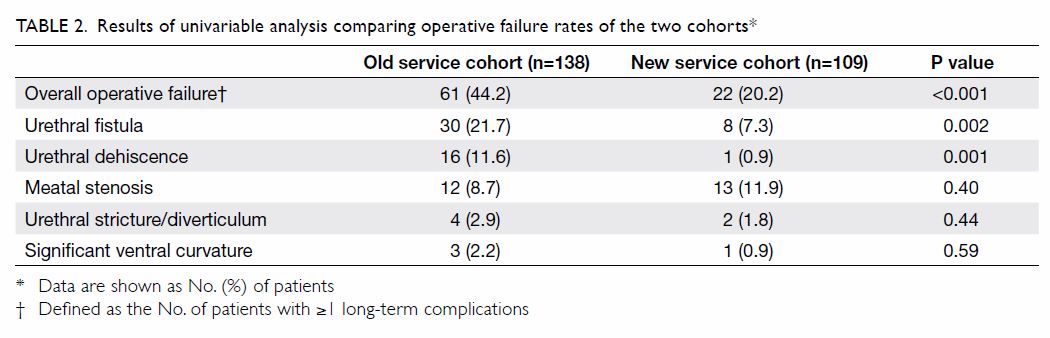

Hypospadias is a congenital abnormality of the

external genitalia in boys, and is defined as an arrest in the

embryological development of the urethra, foreskin, and ventral aspect of

the penis.1 Hypospadias is

characterised by abnormal foreskin with a dorsal hood and an ectopic

urethral meatus, which can be located anywhere from the ventral aspect of

the glans penis, along the penile shaft, within the scrotum, to the

perineum (Fig 1). Hypospadias can be classified broadly into

distal, mid-shaft, or proximal types, with the proximal type being the

most severe form. In general, more severe forms of hypospadias are

associated with a higher incidence and severity of penile ventral

curvature (chordee).1

Figure 1. Distal hypospadias (left) and proximal hypospadias (right)

Ectopic urethral meatus are indicated by arrows

Hypospadias repair is generally recommended in

early childhood for improved function and cosmesis.2 Although advances in surgical techniques have resulted

in favourable outcomes with high success rates for distal hypospadias

repair,3 proximal hypospadias

repair remains challenging, and complication rates have been

reported to be as high as over 50%.4

Postoperatively, the urethral catheter is usually left in place for free

drainage for 5 to 7 days in distal repair5

and from 10 to 14 days in proximal repair.6

In many parts of the world, including North America, patients generally

have a very short stay in hospital and are discharged home with urethral

catheters in situ.7 In contrast,

conventional practice in Hong Kong has been to provide in-patient care

after hypospadias surgery until removal of the urethral catheter.

The Division of Paediatric Surgery and Paediatric

Urology at the Prince of Wales Hospital has been a tertiary referral

centre for hypospadias surgery for over two decades. We introduced a new

service (NS) model in July 2013, which featured the establishment of a

dedicated surgical team and the implementation of an enhanced recovery

pathway (ERP). The present study aimed to compare the outcomes of the NS

model with those of the old service (OS) model. We hypothesised that ERP

implementation by a dedicated surgical team would reduce the risk of early

morbidity and increase the operative success of hypospadias repair.

Methods

Patients

A historical cohort study was conducted on

consecutive patients younger than 18 years who underwent primary repair of

hypospadias in our centre from January 2006 to August 2016. The patients

were identified using both the ICD-10 (International Classification of

Diseases, 10th revision) code related to hypospadias surgery and the

registry of operative procedures entry in operating theatres. We used

ICD-10 code 752.61, which covered the diagnosis of various types of

hypospadias, as well as codes 58.45 and 58.46, which covered various

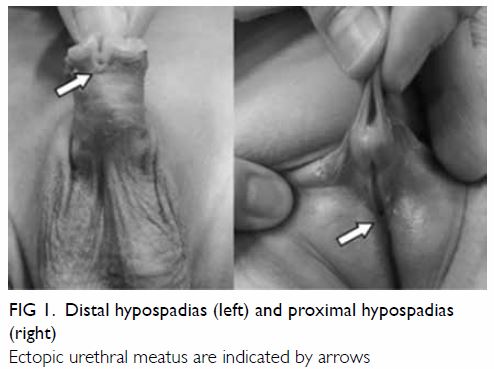

techniques of hypospadias repairs. The patients underwent either one-stage

tubularised incised plate (TIP) repair5

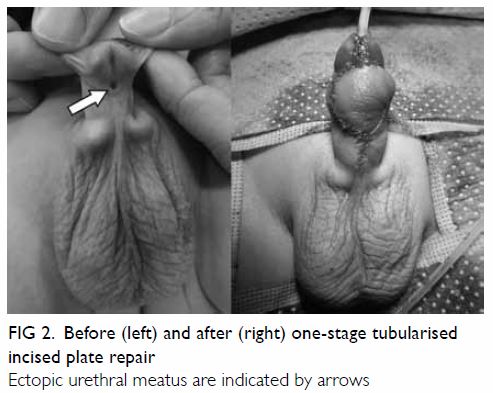

8 (Fig 2), or two-stage preputial flap repair9 (Fig 3), as these two techniques had been our

standard practice for primary repair of hypospadias from distal to

proximal types during the study period. We excluded reoperative

hypospadias repairs and repairs with buccal mucosal graft (BMG).

Reoperative hypospadias surgery is highly variable in complexity, involves

multiple surgical techniques, and is usually investigated separately from

primary hypospadias surgery in literature. Children who undergo BMG

harvest are generally not considered suitable for early hospital

discharge. Moreover, BMG is used rarely in hypospadias surgery, and only

under special circumstances. We also excluded minor hypospadias repairs by

meatal advancement with glansplasty or meatoplasty alone, as such

procedures did not require prolonged urethral catheterisation.

Figure 2. Before (left) and after (right) one-stage tubularised incised plate repair

Ectopic urethral meatus are indicated by arrows

Figure 3. Before (left) and after (right) two-stage preputial flap repair

Ectopic urethral meatus are indicated by arrows

New service model versus old service model

In this study, we assigned patients to two cohorts.

The OS cohort was the control cohort comprising patients on whom we

operated from January 2006 to June 2013. All the patients in this cohort

remained as in-patients until removal of the urethral catheter and

received intravenous antibiotics and regular wound care by medical staff

in the postoperative period. Six specialist paediatric surgeons were

involved in performing the repairs in the OS cohort. The NS cohort

comprised patients who underwent surgery in July 2013 or thereafter.

Patients in the NS cohort were routinely discharged on postoperative day 2

or, rarely, on postoperative day 3, with their urethral catheters in situ.

The dedicated surgical team comprising three (initially only two)

specialist paediatric surgeons who subspecialised in paediatric urology

provided all perioperative services, including handling of the consent

process, surgical repairs, postoperative demonstration of wound care, and

explanation of the discharge plan. Parents or main caregivers were

instructed to perform saline irrigation to the penile wound at home 3 to 4

times per day. Patients received oral antibiotics and were scheduled to

return in a day visit for removal of urethral catheters by a member of the

dedicated team. Parents were instructed to call the ward to arrange an

unplanned consultation visit if necessary. After urethral catheter

removal, patients were followed up at 2 to 4 weeks, 3 months, 6 to 9

months, and then yearly thereafter.

Outcome measures

Medical records were retrospectively reviewed and

data were collected by the authors, who were not blinded to the type of

service model. Data collected were age at time of surgery, type of

hypospadias, type of surgical repair, early morbidity, length of hospital

stay (LOS), unplanned hospital visits, and follow-up evaluation for

long-term complications. Data on the types of hypospadias and surgical

techniques were based on the operative findings and surgical procedures

documented in the operative records. The presence of any early morbidity

was based on investigation results (including urine/wound swab culture)

and/or documentations of urethral catheter dislodgement, wound bleeding,

or wound gaping in the early postoperative period when the urethral

catheter was in situ. The presence of any long-term complications was

based on the findings in the latest follow-up visit, or any

reintervention/reoperation records subsequent to the primary surgery. When

collecting data, we tried to minimise potential bias regarding long-term

complications by defining such complications as meatal stenosis,

neourethra dehiscence, urethral fistula, urethral stricture or

diverticulum, and significant recurrent chordee. All of these long-term

complications required re-intervention/reoperation and were documented if

present.

Primary outcomes of interest were early morbidity

and operative failure. Early morbidity was defined by the presence of one

or more of the following conditions when the urethral catheter was still

in situ: urinary tract infection, catheter dislodgement, and wound-related

events (bleeding/infection/gaping). In the OS cohort, early morbidity was

detected during the hospitalisation period after hypospadias repair. In

the NS cohort, early morbidity was detected at the time of urethral

catheter removal or during unplanned hospital visits before the scheduled

date of urethral catheter removal.

Successful or failed repair was determined during

follow-up in those who had undergone TIP repair or had completed both

stages of the two-stage repair. Operative failure was defined as the

development of one or more of the long-term complications that required

reoperation or reintervention. The secondary outcome measure was the

successful completion rate of ERP. Failure of ERP was defined as any

unplanned hospital visit earlier than the scheduled date for urethral

catheter removal. Failure was further subdivided into day visit or

overnight stay.

Statistical analysis

Discrete variables were expressed as percentage

frequency, whereas continuous variables were reported as mean with

standard deviation or median with interquartile range (IQR). The two

cohorts were compared using Chi squared, Fisher’s exact, Student’s t,

and Mann-Whitney U tests, as appropriate. Using the outcomes of

early morbidity and operative failure, multivariable analysis was

performed using a logistic regression model by the enter method, which

estimated the odds ratios (ORs) and 95% confidence intervals (95% CIs) of

potential associated factors, including age at the time of surgery, type

of hypospadias, type of surgical repair, and the service model.

Statistical analysis was performed with SPSS (Windows version 23; IBM

Corp, Armonk [NY], United States). A two-tailed P value of <0.05 was

considered to be statistically significant. Based on type I error of 0.05

and power of 0.8, 82 to 152 cases in each cohort would be required to show

any two-tailed significant difference in the operative failure rates with

a difference of 15% to 20% between the two cohorts.

Results

There were 302 major primary hypospadias repairs

(OS cohort=176; NS cohort=126) eligible for inclusion in the study. We

identified 107 cases of reoperative hypospadias repairs and one case of

BMG during the study period; these were excluded from this study. No

patients were lost to the first follow-up examination after urethral

catheter removal. The median follow-up durations of the OS and NS cohorts

were 32 (IQR, 20-58) and 20 (IQR, 14-30) months, respectively

(P<0.001).

Of the NS cohort, 111 (88.1%) patients successfully

completed the ERP. Of the 15 patients who failed to complete ERP, 11 (8.7%

of total) returned earlier in an unplanned day visit for wound assessment;

these patients only required reassurance without any intervention. Four

patients (3.2% of total) required additional overnight hospital stay.

Reasons for additional overnight stay were minor wound bleeding (n=1),

dislodgement of urethral catheter (n=2), and social reasons (n=1). The

patient who failed ERP for social reasons was an orphan, and staff at the

orphanage found it difficult to perform wound care at their institution.

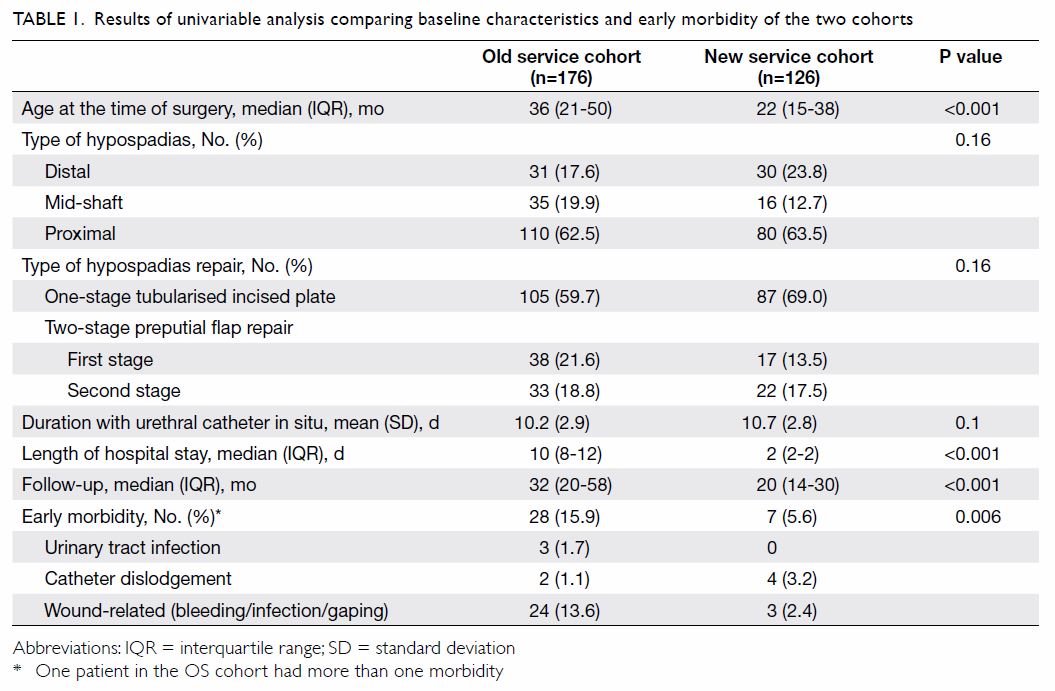

Table 1 summarises the findings comparing patient

characteristics and early morbidity between the two cohorts. The median

age at the time of surgery was older in the OS than the NS cohort

(P<0.001). There was no difference between the two groups in type of

hypospadias, type of surgical procedures, and time interval between

surgery and urethral catheter removal. The median LOS was 2 days in the NS

cohort versus 10 days in the OS cohort (P<0.001). Patients in the NS

cohort experienced less early morbidity than those in the OS cohort (5.6%

vs 15.9%; P=0.006).

Table 1. Results of univariable analysis comparing baseline characteristics and early morbidity of the two cohorts

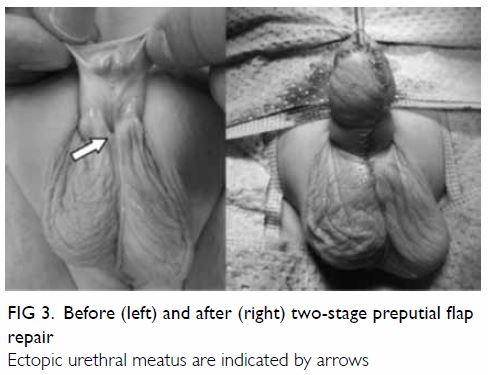

Excluding patients who had received only the first

stage of a two-stage repair, 138 and 109 patients of the OS and NS cohort

were eligible for assessment of operative success, respectively. Patients

in the NS cohort had a lower operative failure rate than those in the OS

cohort (20.2% vs 44.2%; P<0.001). Specifically, patients in the NS

cohort had a lower incidence of urethral fistula and dehiscence than

patients in the OS cohort (P=0.002 and 0.001); there were no differences

in the other complications (Table 2).

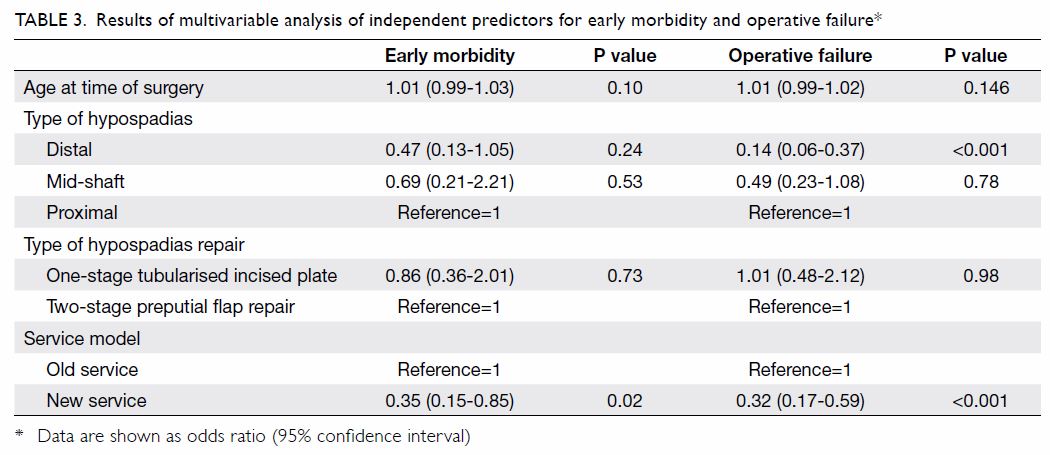

In the multivariable analysis, the NS model was the

only factor that was independently associated with reduced odds of early

morbidity (OR=0.35, 95% CI=0.15-0.85; P=0.02). The NS model was also

associated with reduced odds of operative failure (OR=0.32, 95%

CI=0.17-0.59; P<0.001) compared with the OS model. Compared with

proximal hypospadias, distal hypospadias had reduced odds for operative

failure (OR=0.14, 95% CI, 0.06-0.37; P<0.001). Age at the time of

surgery and surgical techniques were not associated with any difference in

operative success (Table 3).

Table 3. Results of multivariable analysis of independent predictors for early morbidity and operative failure

Discussion

The conventional practice of keeping patients in

hospital until urethral catheter removal after hypospadias surgery is well

reflected from the first annual Surgical Outcome Monitoring and

Improvement Programme Report in 2008/09 to the fifth report in 2012/13

issued by the Hong Kong Hospital Authority.10

11 12

13 14

The median LOS after hypospadias surgery performed in Hospital Authority

hospitals ranged from 9 to 11 days from 2008 to 2013.10 11 12 13 14 It was a traditionally held belief that Hong Kong

parents would not be sufficiently competent to provide proper wound care

at home, and that surgical outcomes would be adversely affected if

patients were discharged from hospital with the urethral catheter in situ.

There was also concern that Hong Kong parents would not welcome the offer

of early hospital discharge, given the reality that the actual costs

billed to parents for in-patient service in Hospital Authority hospitals

are relatively insignificant, compared with other parts of the world where

medical insurance covers only very short in-patient care after hypospadias

surgery. The present study was the first in Hong Kong to investigate the

outcomes of hypospadias surgery after the introduction of an ERP. It is

important to note that our findings do not reflect purely the effect of

ERP but the effect of an NS model that features ERP implementation by a

dedicated surgical team.

Our findings demonstrate that ERP can be applied

effectively and safely to all children who undergo primary hypospadias

repair, regardless of the severity and type of hypospadias. Since its

introduction, we have offered ERP to 126 consecutive patients and none of

the parents or caregivers have declined the offer. Only one patient

discontinued ERP for social reasons, as that child was an

institutionalised orphan. Penile wound care does not require special

skills and involves only wound irrigation with normal saline or clean

water a few times daily. Patients can also be bathed with the urethral

catheters in situ. Adequate preoperative counselling and postoperative

wound care demonstration by the same surgeons who performed the surgery is

the key to promoting the acceptance of ERP among parents.

Almost 90% of our patients completed ERP

successfully. Among those who failed to complete ERP, none had major

adverse events that required surgical intervention and, overall, only 3.2%

of patients required additional overnight stay. The median hospital stay

of 2 days under the NS model was significantly shorter than the median of

10 days in our OS control cohort. In-patient services are precious

resources in our health care system. A much shorter LOS after hypospadias

surgery allows for better allocation of health care resources to other

service areas in which in-patient care is more indicated.

More importantly, our findings suggest that ERP

does not increase early morbidity after primary hypospadias repair. On the

contrary, the NS model was the only factor that was found to independently

predict a reduced risk of early morbidity. Our finding of an early

morbidity rate of 5.6% in the NS model is in agreement with the 4.9%

reported by a previous study in the United States.15 Our finding that most of the early morbidity in the

OS model was wound-related and our observation that, in some of these

patients, the wound swab grew Pseudomonas and extended spectrum

beta-lactamase Escherichia coli raised the concern of possible

hospital-acquired infection. While more evidence is needed to attribute

the high early morbidity rate under the OS model solely to the prolonged

hospital stay, it follows logically that avoiding unnecessary hospital

stay is an effective way to prevent hospital-acquired infection if

in-patient care does not give any additional benefits.

We found a better outcome after primary hypospadias

repair under the NS versus OS model in both univariable and multivariable

analyses. This study not only provides evidence that the implementation of

ERP did not reduce operative success, but also demonstrates how our centre

has responded to the international trend of concentrating hypospadias

repairs among dedicated hypospadias surgeons.2

16 17

In recent years, there has been an international call to stop the practice

of hypospadias repair by occasional surgeons. Proponents of this view hold

that surgeons who perform hypospadias repair should be proficient in using

various techniques to correct the full spectrum of hypospadias defects,

from distal hypospadias to the most complex proximal type.17 18 The

preoperative impression of the ectopic meatal position is not a reliable

reflection of the severity of hypospadias, and many cases are found to be

more complicated intra-operatively.19

Under the NS model, we abandoned our policy of allowing all paediatric

surgical specialists to perform hypospadias surgery; instead, all

hypospadias repairs were concentrated among the three specialists who

subspecialised in paediatric urology.

We believe the improved operative success under the

NS model is attributable to the establishment of the dedicated team, which

has also introduced some technical modifications in the existing

techniques.20 Our overall failure

rate of 20.2% of patients requiring reoperation or re-intervention in the

NS cohort is in agreement with the 18.1% reported by a national

population-based study in the United Kingdom21

and the 24.1% reported by a regional tertiary centre in Europe.22 Both studies included primary repairs of all types of

hypospadias performed by multiple techniques, such as those used in the

present study.21 22 Previous studies have shown that centres that operate

on more than 20 cases per year have a better operative success than those

that operate less frequently,21

and surgeons who perform 20 primary repairs annually have reduced odds of

failure compared with those who perform 10 per year.23 Although the minimum number of hypospadias repairs

per year a surgeon must perform to be considered competent remains

debatable, it is recommended that hypospadias repairs be performed by

surgeons who perform a high volume of repairs and are intellectually

interested in this subject, with continuous review of their own results.17 The current three-member team in

our institution strikes a balance between surgical outcomes and other

practical issues, such as stable staffing, expertise, training, and

succession.

Proximal hypospadias has been known to be

associated with a higher failure rate in primary repair and a higher

reoperation rate than distal hypospadias.24

25 The most recent studies from

major centres have unanimously suggested that the failure rate of primary

repair of proximal hypospadias has actually been underreported in the

literature.6 26 27 Our

finding of increased odds of failure in primary repair of proximal

hypospadias when compared with the distal type is in agreement with the

current evidence. We did not find age at the time of surgery and surgical

techniques to be independent predictors of repair failure, and our finding

is in agreement with other studies.22

We acknowledge the limitations of the retrospective

nature of our study and the lack of randomisation. Data are lacking on

anatomical variations such as quality of urethral plate and glans size,

which may have affected the surgical outcomes. Patients were not

randomised by the type of recovery programme and the study participants

were assigned to the two cohorts according to the service model at the

time. Our results could have been confounded by the effect of accumulating

experience in hypospadias surgery throughout the study period. Data were

collected by investigators who were not blinded to the types of service

models; therefore, there was potential bias in the data collection

process, but inter-rater reliability was not examined. As the ERP was

implemented at the same time as the establishment of the dedicated team,

these two factors could not be analysed separately. Being the more recent

cohort, the patients under the NS model had shorter follow-up duration

than those under the OS model. However, our median follow-up duration of

20 months in the NS cohort compares favourably to that of many published

studies.25

Despite these limitations, our findings demonstrate

the safety and effectiveness of implementing ERP to primary hypospadias

repair for the full spectrum of hypospadias severity. A dedicated surgical

team may play an important role in the successful implementation of ERP

and optimisation of surgical outcomes.

Author contributions

All authors have made substantial contributions to

the concept of this study; acquisition of data; analysis or interpretation

of data; drafting of the article; and critical revision for important

intellectual content.

Funding/support

This research received no specific grant from any

funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Declaration

All authors have no conflicts of interest to

disclose. All authors had full access to the data, contributed to the

study, approved the final version for publication, and take responsibility

for its accuracy and integrity.

Ethical approval

The study protocol was approved by the Joint

Chinese University of Hong Kong–New Territories East Cluster Clinical

Research Ethics Committee. The requirement for patient consent was waived

by the ethics board.

References

1. Baskin LS, Ebbers MB. Hypospadias:

anatomy, etiology, and technique. J Pediatr Surg 2006;41:463-72. Crossref

2. Steven L, Cherian A, Yankovic F, Mathur

A, Kulkarni M, Cuckow P. Current practice in paediatric hypospadias

surgery; a specialist survey. J Pediatr Urol 2013;9(6 Pt B):1126-30. Crossref

3. Wilkinson DJ, Farrelly P, Kenny SE.

Outcomes in distal hypospadias: a systematic review of the Mathieu and

tubularized incised plate repairs. J Pediatr Urol 2012;8:307-12. Crossref

4. Long CJ, Canning DA. Hypospadias: are we

as good as we think when we correct proximal hypospadias. J Pediatr Urol

2016;12:196.e1-5. Crossref

5. Snodgrass WT, Bush N, Cost N.

Tubularized incised plate hypospadias repair for distal hypospadias. J

Pediatr Urol 2010;6:408-13. Crossref

6. Pippi Salle JL, Sayed S, Salle A, et al.

Proximal hypospadias: a persistent challenge. Single institution outcome

analysis of three surgical techniques over a 10-year period. J Pediatr

Urol 2016;12:28.e1-7. Crossref

7. Pohl HG, Joyce GF, Wise M, Cilento BJ

Jr. Cryptorchidism and hypospadias. J Urol 2007;177:1646-51. Crossref

8. Snodgrass W, Bush N. Tubularized incised

plate proximal hypospadias repair: continued evolution and extended

applications. J Pediatr Urol 2011;7:2-9. Crossref

9. McNamara ER, Schaeffer AJ, Logvinenko T,

et al. Management of proximal hypospadias with 2-stage repair: 20-year

experience. J Urol 2015;194:1080-5. Crossref

10. Surgical Outcomes Monitoring &

Improvement Program (SOMIP) report. Volume One: July 2008-June 2009.

Hospital Authority, Hong Kong SAR Government; 2010.

11. Surgical Outcomes Monitoring &

Improvement Program (SOMIP) report. Volume Two: July 2009-June 2010.

Hospital Authority, Hong Kong SAR Government; 2011.

12. Surgical Outcomes Monitoring &

Improvement Program (SOMIP) report. Volume Three: July 2010-June 2011.

Hospital Authority, Hong Kong SAR Government; 2012.

13. Surgical Outcomes Monitoring &

Improvement Program (SOMIP) report. Volume Four: July 2011-June 2012.

Hospital Authority, Hong Kong SAR Government; 2013.

14. Surgical Outcomes Monitoring &

Improvement Program (SOMIP) report. Volume Five: July 2012-June 2013.

Hospital Authority, Hong Kong SAR Government; 2014.

15. Meyer C, Sukumar S, Sood A, et al.

Inpatient hypospadias care: trends and outcomes from the American

nationwide inpatient sample. Korean J Urol 2015;56:594-600. Crossref

16. Springer A, Krois W, Horcher E. Trends

in hypospadias surgery: results of a worldwide survey. Eur Urol

2011;60:1184-9. Crossref

17. Snodgrass W, Macedo A, Hoebeke P,

Mouriquand PD. Hypospadias dilemmas: a round table. J Pediatr Urol

2011;7:145-57. Crossref

18. Malone P. Commentary to “A

standardized classification of hypospadias”. J Pediatr Urol 2012;8:415. Crossref

19. Orkiszewski M. A standardized

classification of hypospadias. J Pediatr Urol 2012;8:410-4. Crossref

20. Tam YH, Pang KK, Wong YS, et al.

Improved outcomes after technical modifications in tubularized incised

plate urethroplasty for mid-shaft and proximal hypospadias. Pediatr Surg

Int 2016;32:1087-92. Crossref

21. Wilkinson DJ, Green PA, Beglinger S,

et al. Hypospadias surgery in England: higher volume centres have lower

complication rates. J Pediatr Urol 2017;13:481.e1-6. Crossref

22. Spinoit AF, Poelaert F, Van Praet C,

Groen LA, Van Laecke E, Hoebeke P. Grade of hypospadias is the only factor

predicting for re-intervention after primary hypospadias repair: a

multivariate analysis from a cohort of 474 patients. J Pediatr Urol

2015;11:70.e1-6. Crossref

23. Lee OT, Durbin-Johnson B, Kurzrock EA.

Predictors of secondary surgery after hypospadias repair: a population

based analysis of 5,000 patients. J Urol 2013;190:251-5. Crossref

24. Castagnetti M, El-Ghoneimi A. Surgical

management of primary severe hypospadias in children: systematic 20-year

review. J Urol 2010;184:1469-74. Crossref

25. Pfistermuller KL, McArdle AJ, Cuckow

PM. Meta-analysis of complication rates of the tubularized incised plate

(TIP) repair. J Pediatr Urol 2015;11:54-9. Crossref

26. Stanasel I, Le HK, Bilgutay A, et al.

Complications following staged hypospadias repair using transposed

preputial skin flaps. J Urol 2015;194:512-6. Crossref

27. Long CJ, Chu DI, Tenney RW, et al.

Intermediate-term followup of proximal hypospadias repair reveals high

complication rate. J Urol 2017;197(3 Pt 2):852-8. Crossref