DOI: 10.12809/hkmj144415

© Hong Kong Academy of Medicine. CC BY-NC-ND 4.0

CASE REPORT

Familial eruptive syringoma

Mahizer Yaldiz, MD1; Cihan Cosansu, MD1;

Mustafa T Erdem, MD1; Bahar S Dikicier, MD1; Zeynep

Kahyaoğlu, MD2

1 Department of Dermatology, Sakarya

University Training and Research Hospital, Sakarya, Turkey

2 Department of Pathology, Sakarya

University Training and Research Hospital, Sakarya, Turkey

Corresponding author: Dr Mahizer Yaldiz (drmahizer@gmail.com)

Case presentations

Case 1

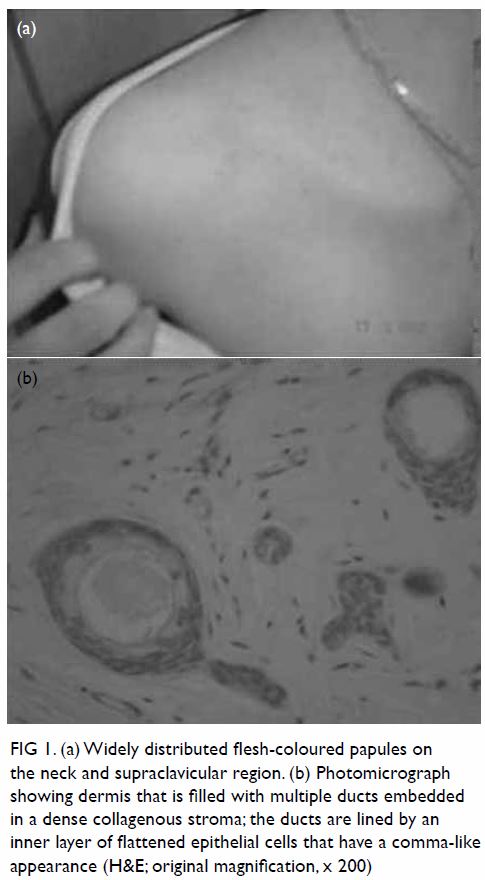

A 20-year-old woman presented with a 4-year history

of progressive papular rash in January 2010. The rash had started on her

neck. The patient was otherwise healthy and had no other skin complaints

and no family history of any skin diseases. She reported that her brother

had similar lesions. Physical examination of the patient revealed widely

distributed flesh-coloured red-brown smooth papules of 1 to 5 mm on the

neck and supraclavicular region (Fig 1a). Skin biopsy and subsequent

histopathological examination revealed dermis that was filled with

multiple ducts embedded in a dense collagenous stroma. The ducts were

lined by an inner layer of flattened epithelial cells that had a

comma-like appearance. Syringoma was diagnosed (Fig 1b).

Figure 1. (a) Widely distributed flesh-coloured papules on the neck and supraclavicular region. (b) Photomicrograph showing dermis that is filled with multiple ducts embedded in a dense collagenous stroma; the ducts are lined by an inner layer of flattened epithelial cells that have a comma-like appearance (H&E; original magnification, x 200)

Case 2

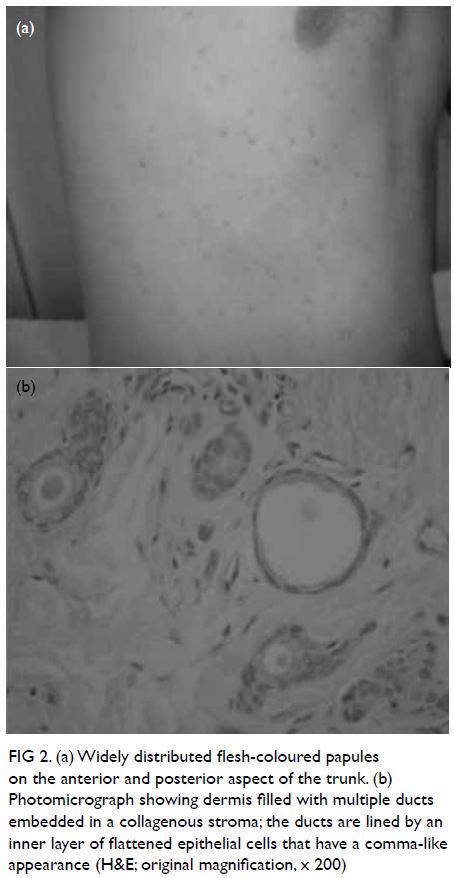

A 25-year-old man, the brother of the patient in

case 1, presented with a 10-year history of progressive papular rash in

January 2010. The rash had started on the back and upper chest. The

patient was otherwise healthy, with no other skin complaints and a

negative family history for any skin diseases, other than his sister.

Physical examination revealed widely distributed, flesh-coloured brown

papules of 1 to 5 mm on the anterior and posterior aspect of the trunk (Fig 2a). Histopathological examination revealed that

the dermis was filled with multiple ducts embedded in a collagenous stroma

and the ducts were lined by an inner layer of flattened epithelial cells

that had a comma-like appearance (Fig 2b).

Figure 2. (a) Widely distributed flesh-coloured papules on the anterior and posterior aspect of the trunk. (b) Photomicrograph showing dermis filled with multiple ducts embedded in a collagenous stroma; the ducts are lined by an inner layer of flattened epithelial cells that have a comma-like appearance (H&E; original magnification, x 200)

On the basis of the clinical and histopathological

findings, both cases were diagnosed as familial eruptive syringoma.

Because this condition is benign, treatment modalities were discussed with

both patients, with particular reference to ‘poor’ cosmetic outcome and

the risk of recurrence. Both patients opted for no intervention. They were

advised to avoid hot environments as much as possible and were given an

open appointment at the dermatology department.

Discussion

The word syringoma is derived from the Greek word syrinx

meaning pipe or tube.1 Syringoma is

a benign adnexal neoplasm that is formed by well-differentiated ductal

elements. Lesions have largely cosmetic significance and affect

approximately 1% of the population.1

2 Syringomas usually first appear

at puberty and are generally asymptomatic; additional lesions can develop

later. Neither of our patients had any symptoms, although rarely

individuals may experience pruritus, especially during perspiration.2 Clinically, syringomas manifest as small skin-coloured

or slightly pigmented papules. Although the peri-orbital region is the

most commonly involved site, the neck, supraclavicular region, and the

anterior and posterior aspect of the trunk may also be affected,

especially in the eruptive form, as seen in our patients.

Syringomas are classified into four clinical types:

localised, familial, generalised, and Down’s syndrome–associated. The

generalised type encompasses multiple and eruptive syringomas.3 Eruptive syringoma is a rare variant that was first

described by Jacquet and Darier in 1887.4

The lesions in eruptive syringoma occur in large numbers and in successive

crops at puberty or during childhood. They can occur on the anterior

chest, neck, upper abdomen, axillae, and the periumbilical region. They

are almost always multiple and most frequently occur on the eyelids and

upper cheeks. Eruptive syringomas are described more frequently in

patients with Down’s syndrome and Ehlers-Danlos syndrome.5 In our patients, there was no such association.

Rarely, a patient with eruptive syringomas may have

a family history of similar lesions. Familial eruptive syringoma is a rare

condition that is likely to be inherited in an autosomal dominant manner.

To the best of our knowledge, only a few cases of familial eruptive

syringoma have been reported worldwide. Our two patients represent typical

cases of familial eruptive syringomas. Reed6

described a family in which seven females and one male in four generations

were affected. Patrone and Patrizi7

reported on a family (mother, daughter, and son) with dominantly inherited

eruptive syringoma. Marzano et al2

reported on a family with multiple syringomas that affected members of

three successive generations, and described in detail a 36-year-old woman

and her 17-year-old son. Lau and Haber8

reported two cases of eruptive syringoma within a family, in which the

lesions were widely distributed over the trunk of a healthy 16-year-old

female and her 19-year-old brother.

Skin biopsies of the lesions are the best means of

diagnosing syringoma, because the microscopic appearance is characteristic

of the condition. Histologically, syringomas are characterised by dilated

cystic spaces lined by two layers of cuboidal cells and epithelial strands

of similar cells. Some of the cysts have what resemble small tails that

look like commas or tadpoles, and in a group they produce a distinctive

paisley-like pattern. There is also a dense fibrous stroma.

The differential diagnosis of eruptive syringomas

must be made while considering other papular dermatosis that frequently

appear during childhood—for example, plane warts, acne vulgaris, lichen

planus, granuloma annulare, papular sarcoidosis, milia, sebaceous

hyperplasia, eruptive xanthoma, urticaria pigmentosa, Darier’s disease,

pseudoxanthoma elasticum, or hidrocystoma. Histological differential

diagnoses include sclerosing (morphea-like) basal-cell carcinoma and

desmoplastic trichoepithelioma. Importantly, syringoma must be

distinguished from microcystic adnexal carcinoma, which has similar

histological features but tends to infiltrate the deep dermis and

subcutaneous tissue.

Despite the availability of numerous treatment

options, their efficacy is limited because the tumours are located in the

dermis and the risk of recurrence is high. Treatment is difficult,

although many lesions respond to very light electrodessication or removal

by shaving. Carbon dioxide laser treatment by the pinhole method and

fractional thermolysis have been reported to be effective in removal. For

larger lesions, surgical removal may be considered. Other treatment

modalities that have been used include cryosurgery, chemical peeling,

dermabrasion, and oral and topical retinoids.9

Our two patients initially requested treatment but then opted for no

intervention.

References

1. Haubrich W. Medical Meaning: A Glossary

of Word Origins. US: American College of Physicians; 2003: 233.

2. Marzano AV, Fiorani R, Girgenti V,

Crosti C, Alessi E. Familial syringoma: report of two cases with a

published work review and the unique association with steatocystoma

multiplex. J Dermatol 2009;36:154-8. Crossref

3. Friedman SJ, Butler DF. Syringoma

presenting as milia. J Am Acad Dermatol 1987;16:310-4. Crossref

4. Jacquet L, Darier J. Hiydradénomes

éruptifs, épithéliomes adénoides des glandes sudoripares ou adénomes

sudoripares. Ann Dermatol Syph 1887;8:317-23.

5. Hertl-Yazdi M, Niedermeier A, Hörster S,

Krause W. Penile syringoma in a 14-year-old boy. Eur J Dermatol

2006;16:314-5.

6. Reed WB. Genetic aspects in dermatology

[in German]. Hautarzt 1970;21:8-16.

7. Patrone P, Patrizi A. Familial eruptive

syringoma [in Italian]. G Ital Dermatol Venereol 1988;123:363-5.

8. Lau J, Haber RM. Familial eruptive

syringomas: case report and review of the literature. J Cutan Med Surg

2013;17:84-8. Crossref

9. Garrido-Ruiz MC, Enguita AB, Navas R,

Polo I, Rodríguez Peralto JL. Eruptive syringoma developed over a waxing

skin area. Am J Dermatopathol 2008;30:377-80. Crossref