Hong Kong Med J 2016 Apr;22(2):158–64 | Epub 20 Nov 2015

DOI: 10.12809/hkmj154549

© Hong Kong Academy of Medicine. CC BY-NC-ND 4.0

ORIGINAL ARTICLE

Evaluation of biological, psychosocial, and

interventional predictors for success of a smoking

cessation programme in Hong Kong

KS Ho, FHKAM (Family Medicine), FHKAM (Medicine);

Bandai WC Choi, MSocSc;

Helen CH Chan, MSocSc, MPH;

KW Ching, MB, BS, FHKAM (Family Medicine)

Integrated Centre for Smoking Cessation, Tung Wah Group of Hospitals;

(c/o) 17/F Tung Sun Commercial, 194-200 Lockhart Road, Wanchai, Hong

Kong

Full

paper in PDF

Full

paper in PDF

Corresponding author: Dr KS Ho (rayhoks@yahoo.com.hk)

Abstract

Introduction: Predictors for smoking cessation have

been identified in different studies but some of the

predictors have been variable and inconsistent. In

this study, we reviewed all the potential variables

including medication, counselling, and others not

commonly studied to identify the robust predictors

of smoking cessation.

Methods: This historical cohort study was conducted in smoking cessation clinics in Hong Kong. Subjects who volunteered to come for free treatment between January 2010 and December 2011 were reviewed. Those under the age of 18 years, or who were mentally unstable or cognitively impaired were excluded. Counselling and quit-smoking medications were provided to the participants. The outcome measure was self-reported 7-day point prevalence abstinence rate at week 26.

Results: Univariate analysis showed that the

following were significant predictors of quitting:

(1) psychosocial variables such as feeling stressed,

feeling depressed, confidence in quitting, difficulty

in quitting, importance of quitting, Smoking Self-Efficacy Questionnaire score; (2) smoking-related variables

such as number of cigarettes smoked per day,

Fagerström Test for Nicotine Dependence score, number

of high-risk situations encountered; (3) health-related variable of having mental illness; (4) basic

demographics such as age, marital status, and

household income; and (5) interventional variables

such as counselling and pharmacotherapy. Multiple

logistic regression showed that the independent

predictors were age, having mental illness, daily

cigarette consumption, Fagerström Test for Nicotine Dependence score, reasons

for quitting, confidence in quitting, depressed mood,

external self-efficacy, intervention with counselling

and medications.

Conclusions: This clinic-based local study offers a

different perspective on the predictors of quitting.

It reminds us to adopt a holistic approach to deal

with nicotine withdrawal, to enhance external self-efficacy

to resist temptation and social influences, to

provide adequate counselling, and to help smokers

to cope with mood problems.

New knowledge added by this study

- A more holistic list of predictors of smoking cessation were included in this local clinic-based study, and differed from many other studies by population survey. Household income, marital status, gender, years of smoking, smoking cohabitant, perceived health, anxious mood, perceived importance, and difficulty in quitting were no longer predictors. Many of these are not modifiable. It is more important to enhance self-efficacy and to use counselling and medication to counter mood problems.

- In clinical practice, we should adopt a holistic approach to smoking cessation by providing more intensive counselling, managing withdrawal symptoms with medication, strengthening external self-efficacy to resist external temptation, and screening for mood problems.

Introduction

Smoking has long been identified as a major

global public health issue. It is the leading cause

of preventable death worldwide and kills about 6

million people each year.1 Although Hong Kong

has the lowest smoking prevalence among the

major cities of China, at 11.1% as reported in 2010,

it still accounts for about 5700 deaths annually,

approximately one fifth of all deaths per year. In 1998,

there were 1324 passive smoking–related deaths reported.2 3

According to the evidence-based MPOWER

measures introduced by the World Health

Organization4 to reduce the demand for tobacco,

to provide smoking cessation services and cessation

support in the public health care system, governments

around the world have put more emphasis on

smoking cessation programmes to reduce the

tobacco-related health risks.5 On 1 January 2007, the

Hong Kong Special Administrative Region (SAR)

Government enacted the Smoking (Public Health)

Ordinance and on 25 February 2009, tobacco tax was

increased by 50%. In 2009, the Tung Wah Group of

Hospitals (TWGHs) was commissioned by the Hong

Kong SAR Government to provide a community-based

smoking cessation service in Hong Kong.

The Integrated Centre on Smoking Cessation

(ICSC) of the TWGHs was set up in different

districts of Hong Kong, namely Shatin, Kwun Tong,

Sheung Shui, Tuen Mun, Mongkok, Wanchai,

Cheung Sha Wan, and Tsuen Wan to provide a

free smoking cessation service to Hong Kong

citizens. An integrated model of counselling and

pharmacotherapy was adopted.6 7

Identification of predictors and determinants

of success in smoking cessation is crucial for

smoking cessation service.8 Over the last decade,

health care professionals have endeavoured to identify

the predictors and characteristics of successful

quitters.9 Overseas studies have identified the

following: old age, high socio-economic status,10 11 12

male gender, younger age at smoking initiation,

previous quit attempts, being married, fewer

depressive symptoms, fewer anxiety symptoms,

lower prior tobacco consumption, lower score of

Fagerström Test for Nicotine Dependence (FTND),

no cohabitating smoker, and high cessation-related

motivation/confidence.8 10 11 12 13 14 Nonetheless, many studies have shown that these predictors are not

always consistent.11 15 This may be due to different methodologies and environments in different studies.

Some studies were population surveys based on

individual recall and did not include interventions.

In this study, we analysed all potential variables

and interventions. With a more comprehensive

list of variables, we hoped to identify some robust

independent predictors of successful quitters.

Methods

Study setting

Clients who attended an ICSC in different districts

in Hong Kong from 1 January 2010 to 31 December

2011 were recruited via smoking cessation hotlines,

referral from health care professionals, or self-referral.

All clients received counselling, and

pharmacotherapy was prescribed if the client agreed.

An average of four face-to-face counselling sessions

were conducted over the first 8-week intensive

treatment phase by registered social workers who

were all trained in tobacco cessation counselling.

Phone follow-up and counselling were also offered

during this treatment phase and between 9 and 12

weeks. The stage of change theory and motivational

interviewing techniques were adopted.16 17 18 Clients

were followed up by telephone at week 26 and

week 52 to ascertain abstinence from smoking. The

medications provided by ICSC included nicotine

replacement therapy (NRT) and non-NRT. The

former included nicotine patches, gum, lozenges,

and inhalers. Oral medications included varenicline

and bupropion. Medications were prescribed

according to the clients’ personal preference and

clinical conditions following a thorough explanation

by counsellors or medical officers. For example, NRT

gum would not be given to a client with dentures

and a patch would not be given to a client with skin

allergy.

Study design, participants, and data collection

This was a historical cohort study. All cases

commenced treatment between 1 January 2010 and

31 December 2011. The inclusion criteria of the

study were adults aged 18 years or above. Clients

who were mentally unstable or cognitively impaired

were excluded.

A structured questionnaire was used to collect

the following information: (i) socio-demographic

variables: age, gender, marital status, education,

monthly household income, number of people living

together; (ii) health-related variables: perceived

health, cessation advice by nurse, cessation advice by

doctor, cessation advice by any medical professional,

severe/chronic illness, mental illness; (iii) smoking-related

variables: age started smoking, years of

smoking, cohabitation with another smoker, number

of cigarettes smoked per day, FTND score,19 previous

quit attempt, number of previous quit attempts, time

of last attempt, reason to quit, high-risk situation;

(iv) psychosocial variables: self-perceived stress,

self-perceived depression, perceived importance,

difficulty and confidence in quitting (from a scale of

0-100), perceived source of social support, Smoking

Self-Efficacy Questionnaire (SEQ-12)20 21; and (v) intervention variables. Consent was obtained and

confidentiality was assured. The questionnaire was

self-administered and illiterate clients were given

help as appropriate. Completed forms were validated

by the counsellors.

Outcome measure

The outcome measure was self-reported 7-day point

prevalence abstinence rate at week 26. Clients who

were not able to be followed up or with an absent

response for smoking status were considered to have

not quitted.

Statistical analyses

Data management and analysis was performed

using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences

(Windows version 22.0; SPSS Inc, Chicago [IL],

US). Univariate logistic regression was used for all

studied predictors. All predictors with a reported P

value of <0.10 were then included in multiple logistic

regression analysis. Backward elimination was used

in the multivariate analysis to identify independent

predictors of abstinence as well as to calculate the

adjusted odds ratio (AOR) and 95% confidence

interval. All statistical analyses were two-tailed tests

and a P value of <0.05 was considered statistically

significant.

Results

Demographics

A total of 4045 clients who attended the ICSC

during 1 January 2010 to 31 December 2011 were

reviewed and 3853 cases who met the inclusion

criteria were analysed. The gender ratio of male-to-female

was approximately 7:3. Their age ranged from 18

to 89 years with a mean of 42 years; mean duration

of smoking of this cohort was 20 years, and mean

cigarette consumption was 18 cigarettes per day

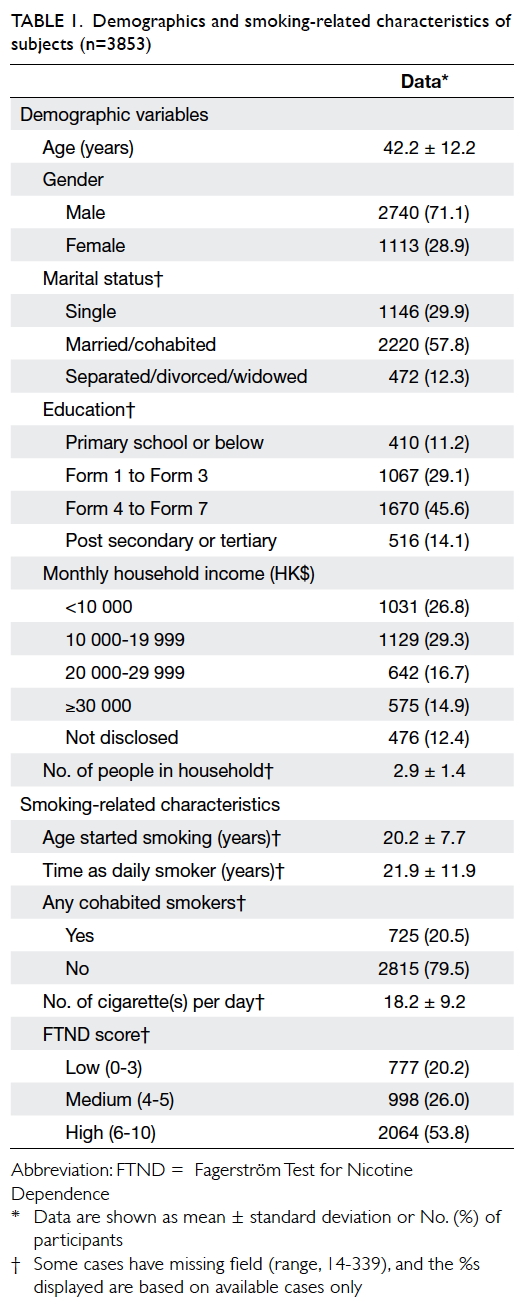

(Table 1).

Univariate logistic regression

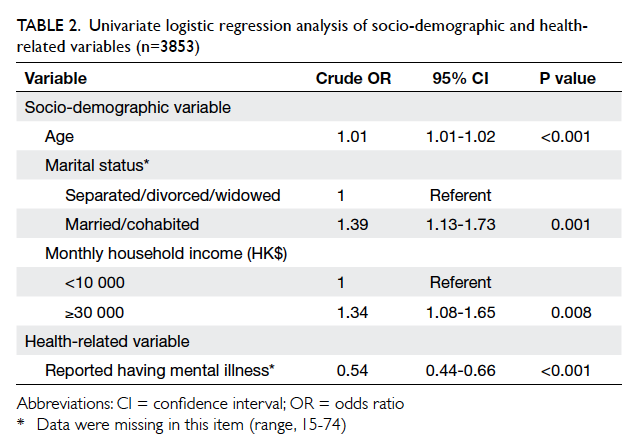

The abstinence rate at week 26 was 35.1% (1353/3853).

Univariate analysis of basic demographic data

revealed that successful quitting was related to

older age, being married, and higher household

income (Table 2). Mental illness was significantly

related to failure to quit but chronic illness was not,

for examples, hypertension, diabetes, and chronic

obstructive pulmonary disease.

Table 2. Univariate logistic regression analysis of socio-demographic and health-related variables (n=3853)

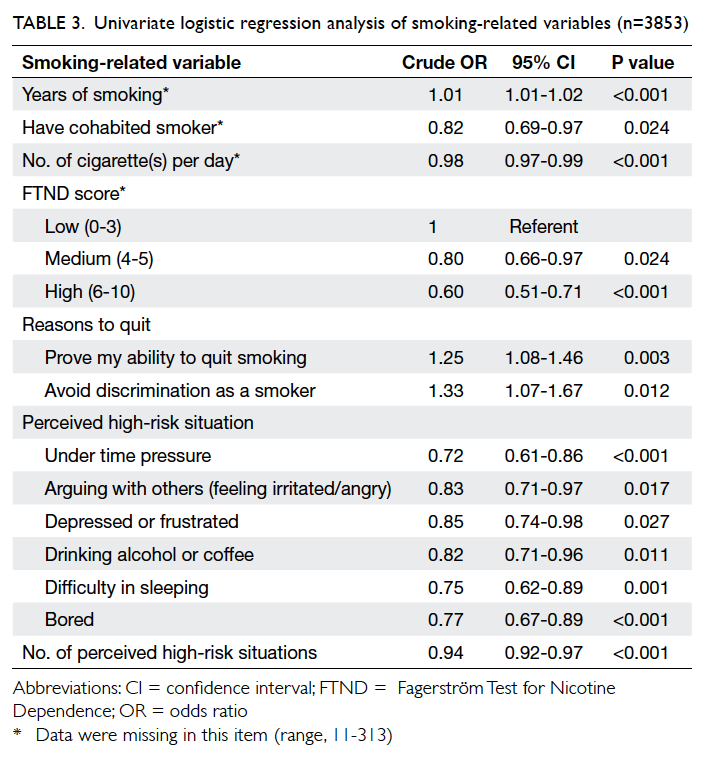

Analysis of smoking-related variables showed

that successful quitting was related to longer years

of smoking, not cohabiting with a smoker, lower

daily cigarette consumption, and lower FTND

score. Successful quitters were more likely to report

“prove my ability to quit smoking” and “avoid

discrimination as a smoker”. A higher number of

high-risk situations in quitting were negatively

related to quit rate. Significant individual high-risk

situations included “under time pressure”, “arguing

with others”, “depressed or frustrated”, “drinking

alcohol or coffee”, “difficulty in sleeping”, and “bored”

(Table 3).

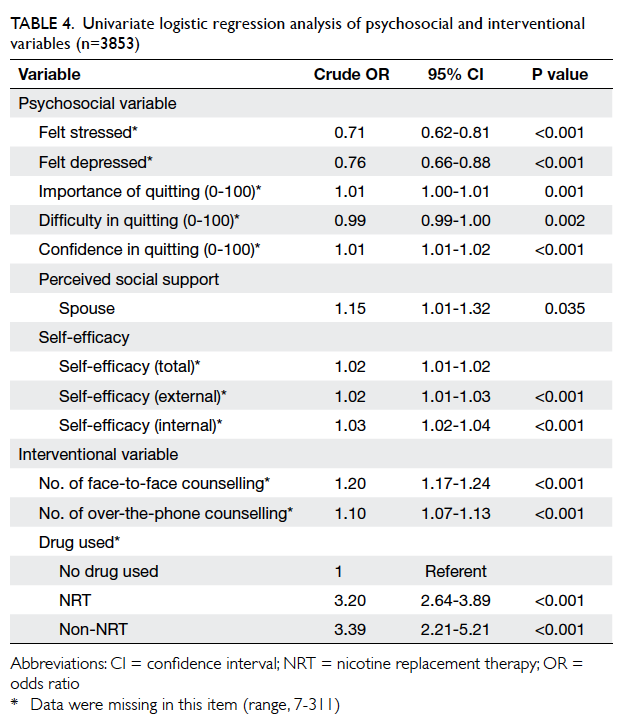

The following psychosocial variables were

correlated to quitting: not feeling stressed, not feeling

depressed, high perceived importance of quitting,

low perceived difficulty in quitting, high confidence

in quitting, perceived support from spouse, and high

SEQ-12 score (Table 4). All interventional variables

were significant predictors of smoking abstinence:

number of face-to-face counselling sessions, over-the-phone counselling, and use of medication.

Table 4. Univariate logistic regression analysis of psychosocial and interventional variables (n=3853)

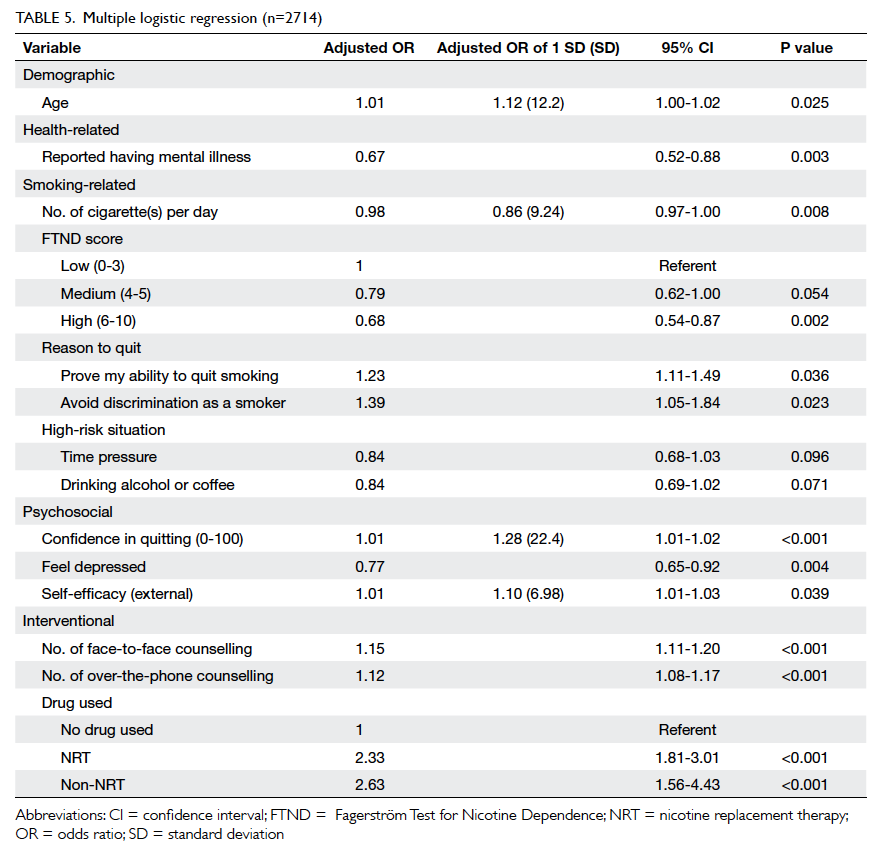

Multiple logistic regression

All items reported P<0.10 in the univariate logistic

regression analysis were included in the multiple

logistic model with backward elimination. Only

subjects with complete data in all fields of the

included items were analysed (n=2714). As shown

in Table 5, independent predictors of smoking

abstinence at week 26 were older age, quitting

based on “prove my ability to quit smoking”, high confidence in quitting,

high external self-efficacy, more counselling

sessions (both office and phone contact), and use

of medication. The following characteristics were

predictive of failure to quit: history of mental illness,

high daily cigarette consumption, high FTND score,

and feeling depressed.

Discussion

This is the first comprehensive study

of predictors of success for smoking cessation in a

local smoking cessation service. Age, mental health,

cigarette consumption, FTND score, reasons to quit,

confidence in quitting, depressive mood, self-efficacy,

sessions of office counselling, phone counselling, and

medication treatment were identified as predictors

among clients who volunteered to quit smoking.

In the univariate logistic analysis, most of the

predictors were consistent with other studies. In

many studies of predictors,15 22 results for gender, number of previous attempts, education level

and social status, years of smoking, and history of

depression have been inconsistent. In our study, a

more comprehensive list of potential predictors from

five domains (namely, demographics, health-related,

smoking-related, psychosocial, and interventional

variables) was included. After multiple logistic

regression analysis, many commonly reported

determinants/predictors were excluded. They

included perceived health, marital status,

cohabitation with a smoker, household income,

gender, years of smoking, perceived importance of

quitting or difficulty in quitting, feeling anxious, and

internal self-efficacy in quitting.

The effect of age appeared to be consistent

with the results of local23 24 and some international studies11 12 13 that older age was an independent predictor.25 Results for the predictive power of male gender have been controversial: some studies have

reported it as a predictor of cessation success,8 10 26 while others have found it to have no significant

effect or a negative effect.12 27 28 Our study could not confirm these findings. In addition, the role of marital

status, education, household income, and number of cohabitants were shown not to be predictive, contrary to some overseas studies.29 30 Nonetheless, consistent with many studies, cigarette consumption and FTND score were negatively correlated with quit rate.8 27 31

Extensive research indicates that individual

motivation, especially intrinsic motivation, is

predictive of the long-term cessation result.8 In

our study, two robust reasons to quit that could

significantly predict abstinence were “prove my

ability to quit smoking” and “avoid discrimination as

a smoker”. This seemed to correspond to the “self-control”

and “social influence” factors of Reasons for

Quitting scale.32 In Hong Kong, smoking in some

designated areas and public places is forbidden.

This may precipitate the “avoid discrimination as a

smoker” response. In service provision, operational

initiatives and promotion strategies may be tailored

to these two areas when motivating smokers to quit.

Perceived depressive mood (AOR=0.77)

and history of mental illness (AOR=0.67) greatly

enervated the success rate of quitting in our

participants. Similar results have been reported

in western countries as well as in Asia.8 33 34 35

This reinforces the importance of implementing

appropriate mental health screening and referral

in smoking cessation clinics. Presence of a chronic

illness was not shown to be predictive although this

may have been due to our relatively small sample size

for this group of clients or because ours was a cohort

of smokers who were motivated to quit. The effect

of chronic illness may thus be attenuated. Studies

have also shown that not all chronic diseases have

the same impact on smoking cessation.36 37

The link between self-efficacy and successful

quitting has long been established.22 38 Both external and internal self-efficacy in SEQ-12 scales have been found to be predictive in smoking cessation in western countries.21 In our study, after adjusting all potential

predictors, a high degree of confidence and external self-efficacy were predictive of cessation, while the

predictive ability of total and internal sub-score of SEQ-12 faded after adjustment. This is consistent

with a previous Hong Kong study.20 Manifestation of

cultural differences in self-efficacy during smoking cessation warranted further investigation. According

to the results in the current study, smoking cessation counselling should focus more on helping clients to

develop techniques to resist external temptation and to enhance external self-efficacy.

Consistent with overseas reviews of smoking

cessation counselling,15 39 our study indicated that the number of sessions of face-to-face counselling or phone support were strong predictors (AOR=1.15 and 1.12, respectively). Both kinds of medication (NRT and non-NRT) were also associated with successful smoking cessation. Most previous predictor studies have not included these parameters, however.

There are some limitations in our study. Since

this was a retrospective case review study of smokers

who were motivated to quit, the results cannot be

generalised to the whole smoking population. In

addition, in the process of multiple logistic regression,

only 2714 clients instead of all study subjects were

analysed. Interventional variables such as office

counselling, phone counselling, and medication

modality were not randomly allocated. Patient

compliance with medication was not evaluated,

thus information on the use of medication may be

biased. Another potential confounding factor was a

small amount of missing data for some predictors.

The effect of job nature and different chronic

illnesses was not included in this study because

of insufficient data; only chronic disease

as a group was analysed. Self-reported 7-day point

prevalence abstinence rate was not biochemically

validated although previous study has shown that

self-reported abstinence does not differ much to

abstinence according to biochemical validation.40

Conclusions

This local study has identified a number of predictors

of smoking abstinence at week 26 in clients who

volunteered to seek treatment from a smoking

cessation clinic. Most large-scale overseas studies

have been based on a population survey. This was

a large-scale comprehensive study performed in

a real-life smoking cessation programme in Hong

Kong. As such, it offers a better understanding of

the determinants of successful quitting. Although

some predictors have not been addressed and need

further study, this study highlights the need for a

holistic approach to the management of nicotine

withdrawal, and to enhance external self-efficacy

and motivation, to provide an adequate number of

counselling sessions and to help smokers cope with

mood problems.

References

1. WHO Report on the global tobacco epidemic. Geneva:

World Health Organization; 2013.

2. Lam TH, Ho SY, Hedley AJ, Mak KH, Peto R. Mortality

and smoking in Hong Kong: case-control study of all adult

deaths in 1998. BMJ 2001;323:361. Crossref

3. Hong Kong Council on Smoking and Health: Annual

Report 2011-2012. Hong Kong: Hong Kong Council on

Smoking and Health; 2012.

4. WHO Report on the global tobacco epidemic, 2008: The

MPOWER Package. Geneva: World Health Organization;

2008.

5. Wang L, Kong L, Wu F, Bai Y, Burton R. Preventing chronic

diseases in China. Lancet 2005;366:1821-4. Crossref

6. 2008 PHS Guideline Update Panel, Liaisons, and Staff.

Treating tobacco use and dependence: 2008 update U.S.

Public Health Service Clinical Practice Guideline executive

summary. Respir Care 2008;53:1217-22.

7. Reducing tobacco use: a report of the Surgeon General—executive summary. Nicotine Tob Res 2000;2:379-95. CrossRef

8. Caponnetto P, Polosa R. Common predictors of smoking

cessation in clinical practice. Respir Med 2008;102:1182-92. Crossref

9. Prochaska JO, DiClemente CC, Velicer WF, Ginpil S,

Norcross JC. Predicting change in smoking status for self-changers.

Addict Behav 1985;10:395-406. Crossref

10. Hymowitz N, Cummings KM, Hyland A, Lynn WR,

Pechacek TF, Hartwell TD. Predictors of smoking cessation

in a cohort of adult smokers followed for five years. Tob

Control 1997;6 Suppl 2:S57-62. Crossref

11. Monsó E, Campbell J, Tønnesen P, Gustavsson G, Morera

J. Sociodemographic predictors of success in smoking

intervention. Tob Control 2001;10:165-9. Crossref

12. Osler M, Prescott E. Psychosocial, behavioural, and

health determinants of successful smoking cessation: a longitudinal study of Danish adults. Tob Control

1998;7:262-7. Crossref

13. Hyland A, Borland R, Li Q, et al. Individual-level predictors

of cessation behaviours among participants in the

International Tobacco Control (ITC) Four Country Survey.

Tob Control 2006;15 Suppl 3:iii83-94. Crossref

14. Haas AL, Muñoz RF, Humfleet GL, Reus VI, Hall SM.

Influences of mood, depression history, and treatment

modality on outcomes in smoking cessation. J Consult Clin

Psychol 2004;72:563-70. Crossref

15. Iliceto P, Fino E, Pasquariello S, D’Angelo Di Paola ME,

Enea D. Predictors of success in smoking cessation among

Italian adults motivated to quit. J Subst Abuse Treat

2013;44:534-40. Crossref

16. Miller WR, Rollnick S. Talking oneself into change:

motivational interviewing, stages of change, and

therapeutic process. J Cogn Psychother 2004;18:299-308. Crossref

17. DiClemente CC, Prochaska JO. Toward a comprehensive,

transtheoretical model of change: stages of change and

addictive behaviors. In: Miller WR, Heather N, editors.

Treating addictive behaviors. 2nd ed. New York: Plenum

Press; 1998: 3-24.

18. Lai DT, Cahill K, Qin Y, Tang JL. Motivational interviewing

for smoking cessation. Cochrane Database Syst Rev

2010;(1):CD006936. Crossref

19. Heatherton TF, Kozlowski LT, Frecker RC, Fagerström KO.

The Fagerström Test for Nicotine Dependence: a revision

of the Fagerström Tolerance Questionnaire. Br J Addict

1991;86:1119-27. Crossref

20. Leung DY, Chan SS, Lau CP, Wong V, Lam TH. An evaluation

of the psychometric properties of the Smoking Self-Efficacy Questionnaire (SEQ-12) among Chinese cardiac

patients who smoke. Nicotine Tob Res 2008;10:1311-8. Crossref

21. Etter JF, Bergman MM, Humair JP, Perneger TV.

Development and validation of a scale measuring self-efficacy

of current and former smokers. Addiction

2000;95:901-13. Crossref

22. Li L, Borland R, Yong HH, et al. Predictors of smoking

cessation among adult smokers in Malaysia and Thailand:

findings from the International Tobacco Control Southeast

Asia Survey. Nicotine Tob Res 2010;12 Suppl:S34-44. Crossref

23. Yu DK, Wu KK, Abdullah AS, et al. Smoking cessation

among Hong Kong Chinese smokers attending hospital as

outpatients: impact of doctors’ advice, successful quitting

and intention to quit. Asia Pac J Public Health 2004;16:115-20. Crossref

24. Abdullah AS, Yam HK. Intention to quit smoking, attempts

to quit, and successful quitting among Hong Kong Chinese

smokers: population prevalence and predictors. Am J

Health Promot 2005;19:346-54. Crossref

25. Fiore MC, Novotny TE, Pierce JP, Hatziandreu EJ, Patel

KM, Davis RM. Trends in cigarette smoking in the United

States. The changing influence of gender and race. JAMA

1989;261:49-55. Crossref

26. Piper ME, Cook JW, Schlam TR, et al. Gender, race,

and education differences in abstinence rates among

participants in two randomized smoking cessation trials.

Nicotine Tob Res 2010;12:647-57. Crossref

27. Vangeli E, Stapleton J, Smit ES, Borland R, West R.

Predictors of attempts to stop smoking and their success

in adult general population samples: a systematic review.

Addiction 2011;106:2110-21. Crossref

28. Bjornson W, Rand C, Connett JE, et al. Gender differences

in smoking cessation after 3 years in the Lung Health Study.

Am J Public Health 1995;85:223-30. Crossref

29. Kim YJ. Predictors for successful smoking cessation in

Korean adults. Asian Nurs Res (Korean Soc Nurs Sci)

2014;8:1-7. Crossref

30. Chandola T, Head J, Bartley M. Socio-demographic

predictors of quitting smoking: how important are

household factors? Addiction 2004;99:770-7. Crossref

31. Abdullah AS, Ho LM, Kwan YH, Cheung WL, McGhee

SM, Chan WH. Promoting smoking cessation among the

elderly: what are the predictors of intention to quit and

successful quitting? J Aging Health 2006;18:552-64. Crossref

32. Curry S, Wagner EH, Grothaus LC. Intrinsic and extrinsic

motivation for smoking cessation. J Consult Clin Psychol

1990;58:310-6. Crossref

33. Kim SK, Park JH, Lee JJ, et al. Smoking in elderly Koreans:

prevalence and factors associated with smoking cessation.

Arch Gerontol Geriatr 2013;56:214-9. Crossref

34. Lasser K, Boyd JW, Woolhandler S, Himmelstein DU,

McCormick D, Bor DH. Smoking and mental illness: A

population-based prevalence study. JAMA 2000;284:2606-10. Crossref

35. Covey LS, Glassman AH, Stetner F. Depression and

depressive symptoms in smoking cessation. Compr

Psychiatry 1990;31:350-4. Crossref

36. Salive ME, Cornoni-Huntley J, LaCroix AZ, Ostfeld

AM, Wallace RB, Hennekens CH. Predictors of smoking

cessation and relapse in older adults. Am J Public Health

1992;82:1268-71. Crossref

37. Freund KM, D’Agostino RB, Belanger AJ, Kannel WB,

Stokes J 3rd. Predictors of smoking cessation: The

Framingham Study. Am J Epidemiol 1992;15:957-64.

38. Gwaltney CJ, Metrik J, Kahler CW, Shiffman S. Self-efficacy

and smoking cessation: a meta-analysis. Psychol

Addict Behav 2009;23:56-66. Crossref

39. Clinical Practice Guideline Treating Tobacco Use and

Dependence 2008 Update Panel, Liaisons, and Staff. A

clinical practice guideline for treating tobacco use and

dependence: 2008 update. A U.S. Public Health Service

report. Am J Prev Med 2008;35:158-76.

40. Patrick DL, Cheadle A, Thompson DC, Diehr P, Koepsell

T, Kinne S. The validity of self-reported smoking, a review

and meta-analysis. Am J Public Health 1994;84:1086-93. Crossref