DOI: 10.12809/hkmj144411

© Hong Kong Academy of Medicine. CC BY-NC-ND 4.0

CASE REPORT

Trampoline-related injuries in Hong Kong

MY Cheung, MB, BS; CL Lai, MB, BS; Wilson HY Lam, MB, BS; James SK Lau, BSc, MB, BS; Aaron KH Lee, MB, ChB; Gabrielle G Yuen, MB, BS; YK Chan, FRCS, FHKAM (Orthopaedic Surgery); WL Tsang, FRCS, FHKAM (Orthopaedic Surgery)

Department of Orthopaedics and Traumatology, Pamela Youde Nethersole Eastern Hospital, Chai Wan, Hong Kong

Corresponding author: Dr James SK Lau (jameslau@gmail.com)

Case reports

The following three cases highlight the potential

serious consequences of trampolining.

Case 1: Lisfranc fracture

A 27-year-old woman with good past health was

admitted with left foot pain and swelling in July

2014. She fell with axial loading on an inverted and

plantar-flexed left foot while trampolining. Physical

examination showed bruising on the dorsum of her

left foot with tenderness over the base of the first and

second metatarsals. Range of movement was limited

by pain. Subsequent X-ray showed widening of the

Lisfranc joint with base avulsion (Fig a). Lisfranc

fracture was diagnosed. Open reduction with screw

and K-wire fixation were performed and a resting

ankle-foot orthosis was given. On follow-up 2 weeks

after surgery, sensation and circulation in the toes

were good. Range of movement was still limited

by pain, however. She was encouraged to move her

ankle and toes, and to mobilise with heel-walking at

6 weeks postoperatively.

Figure. Images of the case illustrations

(a) X-ray of the left foot (dorsoplantar view) of patient 1 showing widening of Lisfranc joint (arrow). (b) Computed tomography of the spine (reconstructed sagittal view) of patient 2 demonstrating two-column fractures of T12 and L1 (arrows). (c) X-ray of the left ankle (lateral view) of patient 3 illustrating posterior talus dislocation (arrow)

Case 2: vertebral fracture

A 25-year-old swimming instructor with good past

health was admitted for thoracolumbar back pain

after jumping and falling from 1 metre while trampolining in August 2014.

He landed on his upper back with his body flexed

on a trampoline. On examination, there was local

tenderness at the thoracolumbar junction. His power

and sensation across L2 to S1 were normal, reflexes

were present, and anal sensation and tone were

intact. Lumbosacral spine X-ray showed collapsed

T12 and L1 with local kyphosis of 25°. Computed

tomographic scan was performed subsequently,

detailing a two-column fracture of T12 and L1 with

anterior wedging of 20% (Fig b). He was put on a rigid

thoracolumbar orthosis for 8 weeks and prescribed

analgesics. Close monitoring for further collapse was

warranted. During follow-up, he had no complaints

of pain or neurological symptoms. Follow-up X-ray

of the lumbosacral spine was static.

Case 3: ankle dislocation

A 22-year-old woman with good past health was

admitted with left ankle pain and deformity after

landing on a trampoline with plantar flexion and

ankle inversion in August 2014. Physical examination

revealed a deformed left ankle joint in medial

rotation and plantar flexion. There was bruising over

the left foot dorsum and marked tenderness over the

whole ankle joint line. She could move her toes only

slightly. Distal circulation was intact, but sensation

was reduced over her left foot and toes. X-ray of the

left ankle showed posterior talus dislocation without

definite fracture (Fig c). Closed reduction was

performed under sedation and a short leg slab was

applied. Post-reduction X-ray showed a congruent

ankle joint. Computed tomography showed no

fracture. Magnetic resonance imaging of the left

ankle showed small cortical fractures at the medial

body of talus and posterior aspect of distal talus,

complete tear of the calcaneofibular ligament and

anterior talofibular ligament, and a partial thickness

tear of the deep deltoid ligament. Immobilisation

with a short leg cast is planned after oedema has

subsided.

Discussion

In Hong Kong, trampolining was once a part of

school physical education classes since it improves

motor control and increases physical activity.1

However, following a trampoline incident in

1991 that resulted in quadriplegia,2 its popularity

dwindled. Since the opening of the first trampoline

park in Hong Kong in late July 2014,3 an increase in

the number of trampoline-related injuries requiring

admission to our department has been noted. Eight

trampoline-related admissions were observed in

less than 2 months. It has been estimated that the

incidence of injuries that required admission to our

unit was 1.9 per 10 000.4 The reasons of admission

included Lisfranc fracture, vertebral fracture,

ankle dislocation, anterior cruciate ligament tear

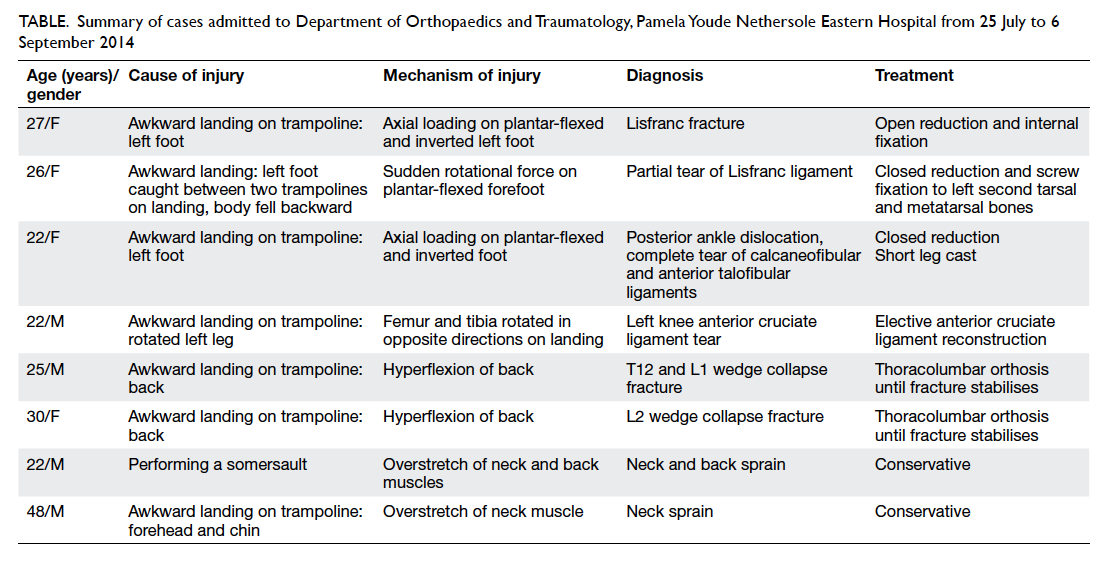

of the knee, and neck and back sprains (Table).

All patients were previously healthy but had no

trampolining experience when they attended the

indoor trampoline park for recreation and injured

themselves while landing on a trampoline mat.

Physicians and the general public need to be aware

that trampolining can result in significant injuries,

leading to acute hospital admission or even early

surgical attention.

Table. Summary of cases admitted to Department of Orthopaedics and Traumatology, Pamela Youde Nethersole Eastern Hospital from 25 July to 6 September 2014

Literature review

In a New Zealand study, most trampoline injuries

occurred on home trampolines.5 With its limited

space, home trampolining is not popular in Hong

Kong, thus there is a lack of local studies. Nonetheless

since the recent opening of a trampoline park in

our cluster, the awareness of trampoline-related

injuries has risen rapidly. In less than 2 months,

eight patients were admitted for trampoline-related

injuries. Their age ranged from 22 to 48 years, with

seven aged between 22 and 30 years. In overseas

studies, the highest incidence of injury occurred in

patients under 20 years of age.5 6 This is related to accessibility to home trampolines.

Nysted and Drogset1 evaluated a total of 551

injuries, among which 292 cases were secondary to

awkward landing on the trampoline1 in comparison

with seven out of eight cases observed locally. The

second and third most common mechanism of

injury was falling off the trampoline and collision

with another person, respectively.1 Falling off the

trampoline is not possible in our setting since

there are multiple interconnected trampolines

that are levelled with a padded ground. The fourth

commonly reported injury was caused by performing

a somersault (11%)1 on the trampoline which was

the cause of injury in our eighth patient. In another

study by Alexander et al,7 a similar trend is seen. A

majority of injuries (42%) were due to landing badly

on the trampoline. Injuries from the frame/springs,

presence of multiple jumpers, and getting on/off constituted 19%, 10% and 2% of all trampoline

injuries, respectively. In short, serious injuries can

happen even when landing on a soft surface such

as a trampoline mat where participants may be less

cautious.

In our report, there was a lack of injuries

involving the upper extremities, contrary to the

findings of overseas studies. This could be skewed

by the small sample size as well as the nature of

trampolining; untrained adults tend to be more

conservative and land axially on their feet. Hence the

majority of our cases involved the lower extremities

(50%), and is congruent with the findings of Hume

et al5 and Nysted and Drogset1 (46% and 45%, respectively). Another important point to note is

that injuries involving the spine are not uncommon

(25%).

Regarding the types of injury, fractures

constituted a significant proportion of injuries in the

studies of Nysted and Drogset1 and Chalmers et al8 (36% and 68%, respectively), and was also the case

in our study (37.5%). A small proportion of local

injuries were dislocation, which is observed in the

same studies.1 8

Safety measures

In addition to regular maintenance and a readily

available first-aid kit, a number of measures can

be taken that may lower the injury rates. Most

importantly, participants should be verbally briefed

by the facility provider about the risks and dangers of

trampoline use.9 For example, only one participant

should be on a trampoline mat at any given time.9

Black and Amadeo10 emphasised the importance

of multiple jumpers as a risk factor for injuries due

to the elastic recoil generated by a larger person

jumping on the mat.

In order to familiarise participants with the

elasticity of a trampoline, trampolines of lower

elasticity should be provided for warm-up. This is

a common practice in formal training,11 and may

reduce the chance of awkward landing due to motor

incoordination. Another suggestion is to restrict

beginners from performing complex movements

such as somersaults and flips.9 To achieve this, the

provider may provide a separate area for advanced

participants. It is important to note that padding to

cover frames has not been shown to reduce injuries.7

Injury rates should be monitored8 closely by the

provider so that the effectiveness of safety measures

can be evaluated.

Limitations and suggestions

Injuries that did not require hospital admission were

not included, such as those in patients who presented

to general practitioners or who were discharged from

the emergency department. Furthermore, this report

can only include cases that occurred up to the time

of writing. This may underestimate the problem and

lead to inaccurate interpretation. It is also difficult

to draw comparisons with epidemiological data

from other countries where the majority of injuries

arise from home trampoline use and not from

trampoline parks. Lastly, although trampolining

may be perceived as a dangerous physical activity,

this may not be the case; the risk of injury is not high

compared with other physical activities.

Acknowledgement

We thank Dr Siu-ho Wan for encouragement,

guidance, and assistance throughout the preparation

of the case reports.

References

1. Nysted M, Drogset JO. Trampoline injuries. Br J Sports

Med 2006;40:984-7. Crossref

2. Tang SP. I want euthanasia [In Chinese]. Hong Kong: Joint

Publishing (HK) Co Ltd; 2007.

3. South China Morning Post. Hong Kong’s first trampoline

park, Ryze, is bound to be fun. Available from: http://yp.scmp.com/news/sports/article/90339/hong-kongs-first-trampoline-park-ryze-bound-be-fun. Accessed 4 Sep 2014.

4. South China Morning Post. Trampoline centre Ryze proves

a summer hit with Hong Kong youth. Available from: http://www.scmp.com/news/hong-kong/article/1565201/trampoline-centre-ryze-proves-summer-hit-hong-kong-youth.

Accessed 26 Feb 2014.

5. Hume PA, Chalmers DJ, Wilson BD. Trampoline injury

in New Zealand: emergency care. Br J Sports Med

1996;30:327-30. Crossref

6. Hammer A, Schwartzbach AL, Paulev PE. Trampoline

training injuries—one hundred and ninety-five cases. Br J

Sports Med 1981;15:151-8. Crossref

7. Alexander K, Eager D, Scarrott C, Sushinsky G.

Effectiveness of pads and enclosures as safety interventions

on consumer trampolines. Inj Prev 2010;16:185-9. Crossref

8. Chalmers DJ, Hume PA, Wilson BD. Trampolines in New

Zealand: a decade of injuries. Br J Sports Med 1994;28:234-8. Crossref

9. Council on Sports Medicine and Fitness, American

Academy of Pediatrics, Briskin S, LaBotz M. Trampoline

safety in childhood and adolescence. Pediatrics

2012;130:774-9. Crossref

10. Black BG, Amadeo R. Orthopedic injuries associated

with backyard trampoline use in children. Can J Surg

2003;46:199-201.

11. USA Gymnastics. Basic trampoline—the beginning

steps. Available from: https://usagym.org/pages/home/publications/technique/2000/3/basictrampoline.pdf.

Accessed 8 Sep 2014.