Hong Kong Med J 2015 Aug;21(4):345–52 | Epub 19 Jun 2015

DOI: 10.12809/hkmj144399

© Hong Kong Academy of Medicine. CC BY-NC-ND 4.0

REVIEW ARTICLE

Strategies and solutions to alleviate access block and overcrowding in emergency departments

Stewart SW Chan, MSc, FHKAM (Emergency Medicine);

NK Cheung, MB, ChB, FHKAM (Emergency Medicine);

Colin A Graham, MD, FCEM;

Timothy H Rainer, MD, FIFEM

Emergency Department, Prince of Wales Hospital; Accident and Emergency Medicine Academic Unit, The Chinese University of Hong Kong, Shatin, Hong Kong

Corresponding author: Dr Stewart SW Chan (stewart_chan@hotmail.com)

Abstract

Objectives: Access block refers to the delay caused

for patients in gaining access to in-patient beds after

being admitted. It is almost always associated with

emergency department overcrowding. This study

aimed to identify evidence-based strategies that can

be followed in emergency departments and hospital

settings to alleviate the problem of access block

and emergency department overcrowding; and to

explore the applicability of these solutions in Hong

Kong.

Data sources: A systematic literature review was

performed by searching the following databases:

CINAHL, Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews,

EMBASE, MEDLINE (OVID), NHS Evidence,

Scopus, and PubMed.

Study selection: The search terms used were

“emergency department, access block, overcrowding”.

The inclusion criteria were full-text articles,

studies, economic evaluations, reviews, editorials,

and commentaries. The exclusion criteria were

studies not based in the emergency departments or

hospitals, and abstracts.

Data extraction: Abstracts of identified papers

were screened, and papers were selected if they

contained facts, data, or scientific evidence related

to interventions that aimed at improving outcome

measures for emergency department overcrowding

and/or access block. Papers identified were used to locate further references.

Data synthesis: All relevant scientific studies

were evaluated for strengths and weaknesses using

appraisal tools developed by the Critical Appraisal

Skills Programme. We identified solutions broadly classified into the following categories: (1)

strategies addressing emergency department

overcrowding: co-locating primary care within the

emergency department, and fast-track and emergency

nurse practitioners; and (2) strategies addressing

access block: holding units, early discharge and

patient flow, and political action—management and

resource priority.

Conclusion: Several evidence-based approaches

have been identified from the literature and effective

strategies to overcome the problem of access block

and overcrowding of emergency departments may

be formulated.

Introduction

In the past 20 years, access block and emergency

department (ED) overcrowding have emerged and

given rise to major problems, affecting the health

care systems of developed countries, including those

in the US, UK, and Australia.1 2 3 4 In Australia, the

term ‘access block’ is defined as the situation where

patients in EDs are unable to gain access to in-patient

beds within 8 hours of presentation to the ED.4 In

the UK, it is defined as 4 hours or more from arrival

to admission, transfer, or discharge.3 Although ED

overcrowding may be due to many factors other

than access block—such as increased ED attendances,

inappropriate use of ED services, or deficiencies in

ED medical and nursing staffing levels or patterns—access block is almost always associated with

overcrowding, and significantly leads to poor quality

of care outcomes.5 Numerous studies from the US,

UK, Canada, and Australia have shown that access

block causes ED overcrowding and affects quality

of care.6 7 8 9 10 Bullard et al8 reported that admitted patients “boarding” in the ED (ie access block) was

the number one advocacy issue for the Canadian

Association of Emergency Physicians. Richardson9

conducted a survey from 83 EDs in Australia and

concluded that overall, caring for patients waiting for

beds represented 40% of the workload of ED staff in

major hospitals. Apart from this, ED overcrowding

affects the outcomes of admitted patients. Sun et al10

performed a retrospective cohort analysis of 995 379

ED visits resulting in admissions in 187 acute care

hospitals in California, US, and found that periods

of ED overcrowding were associated with increased

mortality, longer length of stay, and higher costs for

admitted patients.

Access block and ED overcrowding are

detrimental to the morale of ED staff members.11

Moreover, a survey of 400 admitted ED patients by

Bartlett and Fatovich12 in Perth, Australia reported

that patients preferred waiting in ward corridors for a

ward bed if there were no ED cubicles available. This

study alone showed that access block, independent

of overcrowding, affects patients. Jelinek et al13 also

showed that overcrowding in the ED affects the

supervision of junior doctors.

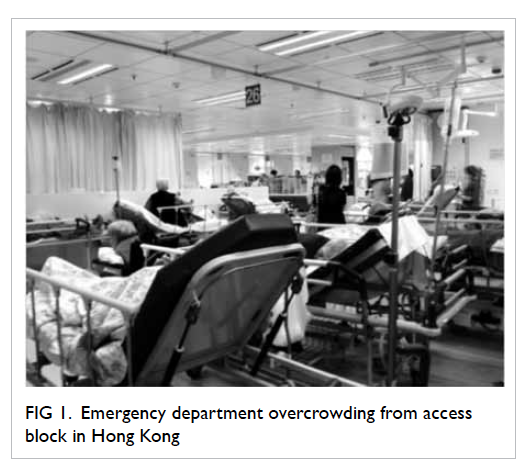

Overcrowding and access block in EDs are

rapidly becoming problematic areas for the health

system even in Hong Kong. Figure 1 shows a photograph depicting the crowded ED with literally

dozens of patients waiting for admission, which is

almost an everyday scenario in a major teaching

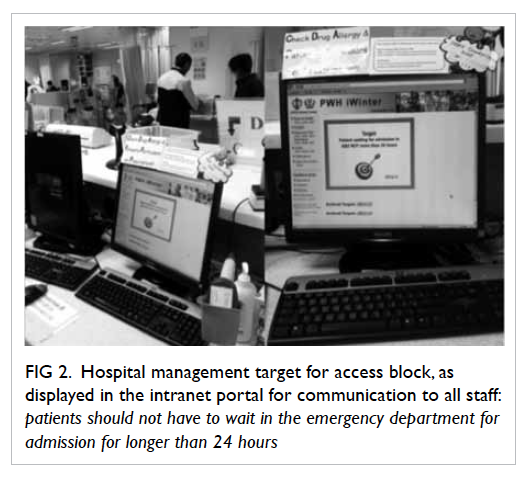

hospital in Hong Kong. At the time of drafting of

this manuscript, the hospital management had set a

target that patients waiting for admission should not

have to wait longer than 24 hours (Fig 2), a target that

is ludicrous by international standards. This review

therefore aimed to answer the question: what are

evidence-based strategies and solutions that can be

applied within the ED and the hospital setting that are

shown to be effective in alleviating ED overcrowding

and access block? Further, we explored the relevance

and applicability of these solutions identified with

respect to the Hong Kong setting.

Figure 2. Hospital management target for access block, as displayed in the intranet portal for communication to all staff: patients should not have to wait in the emergency department for admission for longer than 24 hours

Methods

A search for English language papers was performed

on the following electronic databases: CINAHL,

Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, EMBASE,

MEDLINE (OVID), NHS Evidence, Scopus, and

PubMed. The search terms used were: “emergency

department, access block, overcrowding”. The

inclusion criteria were: full-text articles, randomised

controlled trials, systematic reviews, cohort studies,

case-control studies, qualitative studies, economic

evaluations, narrative reviews, editorials, and

commentaries. The exclusion criteria were studies

with interventions that were not primarily based in

the ED or hospital (eg primary care or pre-hospital

strategies) and abstracts.

Abstracts of identified papers were screened,

and papers were selected if they contained facts,

data, or scientific evidence related to interventions

that aimed at improving outcome measures for

ED overcrowding and/or access block. References

identified from these articles were used to locate

further references. All relevant scientific studies

were evaluated for strengths and weaknesses by

using appraisal tools developed by the Critical

Appraisal Skills Programme, which can be accessed

through the link: <http://www.casp-uk.net/>.

Results

The number of citations returned from the search

was as follows: CINAHL (11), Cochrane Database

of Systematic Reviews (0), EMBASE (39), MEDLINE

(OVID) [11], NHS Evidence (166), Scopus (32), and

PubMed (20). These citations were screened for

relevance and fulfilment of inclusion and exclusion

criteria. A total of 22 papers were selected which

included one systematic review, 12 cohort studies, seven

reviews, one qualitative study, and one expert opinion

article. From these article references, more papers

that were relevant to the subject were found and

studied.

The review identified numerous management

interventions that were likely to be effective in

improving outcome measures to prevent ED

overcrowding and access block. They are organised

and listed below:

(1) Strategies primarily addressing ED

overcrowding:

(a) Co-locating primary care within the ED; and

(b) Fast-track and emergency nurse practitioners (ENPs).

(a) Co-locating primary care within the ED; and

(b) Fast-track and emergency nurse practitioners (ENPs).

(2) Strategies primarily addressing access block:

(a) Holding units;

(b) Early discharge and patient flow; and

(c) Political action—management and resource priority.

(a) Holding units;

(b) Early discharge and patient flow; and

(c) Political action—management and resource priority.

Discussion

Strategies primarily addressing overcrowding in emergency departments

Co-locating primary care within the emergency departments

Overcrowding of ED has been attributed to primary

care attenders inappropriately utilising the ED.14 15

If this were true, then the provision for additional

number of primary care practitioners to the ED

physician workforce would follow as a possible

logical solution to counter ED overcrowding.

There is a wide variation in the incidence of

primary care attendance in the ED, with figures

ranging from 6% to 60% among hospitals in the UK.16

Variations in these studies may be due to differences

in concept as to what primary care problems need

or need not be treated in the ED.17 It was shown that

expanding primary care and out-of-hour services

may lead to decreased primary care attendance

at EDs.18 A considerable proportion of patients

attending the ED could be adequately looked after

by general practitioners (GPs) or primary care

physicians. Although it is considered cost-effective,

one study did find that GPs tend to utilise more

resources and another study showed that providing

primary care services in the ED actually increased

the number of primary care attendances, resulting in

increased waiting time.19 20 21

The synthesis of all these studies suggests that

co-locating primary care within the ED is a workable

solution in most instances, but the extent of the

benefits will depend on the relative importance of

primary care attendance as a cause for overcrowding,

which differs from country to country and from one

hospital to another. In Hong Kong, the principle

behind this solution has already been applied in

several hospitals, but is yet to be developed into a

territory-wide systematic strategy. In the past several

years, some hospitals have started to employ part-time

GPs to provide regular session-based services

in the ED. Their duty is to handle cases of low acuity and this has considerably helped in reducing

congestion at EDs. Although there have not been

any published data to show that these arrangements

improve waiting times in Hong Kong, our experience

is that these locum doctors do alleviate overcrowding

whenever they are present. In our hospital’s ED,

the GPs are encouraged to discuss difficult cases

with senior doctors in the EDs, who would advise

on treatment or disposition, or even take over the

patient for further management. In this way, quality

of care can be ensured. This approach seems to be

promising and a model that can be improved and

developed further. Based on the cited evidence,

this may have implications beyond just solving the

manpower number issue unto a more comprehensive

strategy and direction in health care planning.

Fast-track and emergency nurse practitioners

The concept of fast-track service stems from the fact

that most of the crowding in an ED may actually

involve low acuity patients like those with minor

injuries or minor illnesses. Therefore, fast-track

services for such patients may be an important

front-end operational strategy to relieve congestion.

If the fast-track services are efficiently designed and

provided by dedicated staff at a designated area in

the ED, we can expect improvement in flow and

elimination of wastes, which may result in shorter

overall waiting times. A review by Yoon et al,22

commissioned by the Canadian Health Technology

Assessment, concluded that fast-track systems in EDs

are efficient, cost-effective, safe, and satisfactory for

patients. Since 2002, the UK National Health Service

(NHS) has also encouraged the national use of fast-track systems under the ‘see and treat’ principle.3

The introduction of fast-track systems has been

investigated in a wide variety of clinical settings.23 24 25 26

These studies found that fast-track systems decreased

patient waiting times and shortened the overall

length of stay in EDs. The rate of patients “left without

being seen” was also reduced. Further, quality of

care was not compromised, as shown by data on

patient satisfaction, unscheduled reattendance, and

mortality rates. A key principle of using fast-track

systems is to have experienced and competent staff

designated to ‘see and treat’ the patients.

Studies also suggest that having ENPs

incorporated into these systems for seeing and

treating front-end strategies may further increase

efficiency in relieving overcrowding. Emergency

nurse practitioners have been increasingly used

in EDs in the UK since the 1990s.27 Carter and

Chochinov28 performed a systematic review of ENPs

working in the ED by looking at the key outcome

measures of waiting times, patient satisfaction,

quality of care, and cost-effectiveness. They found

that ENPs can reduce waits, lead to high patient

satisfaction, and provide quality of care equivalent

to a mid-grade resident doctor, although the costs

of resident doctors are higher. A recent Australian

study which included ENPs and physicians working

in an ED fast-track unit of a tertiary hospital showed

that while the quality of care was high in both

groups, patient satisfaction score was significantly

higher with the ENP group than with the physician

group.29

In Hong Kong, formal training of ENPs has

been developed only recently. This started when two

experienced emergency nurses from the authors’

institution were funded by a charitable foundation

to receive ENP training in the UK in 2006. They

subsequently started their ENP practice in June

2007 with a scope of practice focusing primarily

on minor injuries. In 2010, a university master’s

programme for advanced ENPs was first established

in Hong Kong to provide education and training

for emergency nurses. Currently in our ED, ENPs

are on roster for 5 days a week to ‘see and treat’

patients, numbering up to 20 patients per 8-hour

shift, with holistic responsibilities which include

performing minor procedures such as suturing in

conjunction with a vast array of nursing care services

for the patients they have seen. A retrospective study

from our department reported that ENP services

reduced waiting time and processing time without

compromising quality of care.30 The future training

and development of more ENPs into the workforce,

and their incorporation into an ED fast-track

service, are promising strategies for alleviating ED

overcrowding in Hong Kong.

Nevertheless, there are certain issues that are

still stumbling blocks. Currently, nurses in Hong

Kong are not legally allowed to prescribe medications

and issue sick leave certificates. Therefore, ENPs are

not completely independent although they carry a

good amount of clinical load. The ENPs also need

autonomy to refer patients for X-rays and allied

health services (eg physiotherapy) and these are

important barriers for effective development of their

service. Finally, there is a debate as to how cost-effective

it is to designate an ENP (at least at the grade

of Advanced Practising Nurse) to perform duties

that can be performed by a junior resident doctor.

The answer to this question will depend very much

on the relative supply of each of these categories of

staff prevailing at that point of time.

Strategies primarily addressing access block

The possible causes of access block include (1) the

disinclination for clinicians to discharge patients,

(2) inefficient flow in the discharge process, and (3)

genuinely insufficient bed capacity. These causes of

access block are discussed further and addressed

under the following three possible solutions.

Holding units

Holding units are clinical decision units or

observation units within the ED. In the US, reviews

by the Institute of Medicine Committee found that

such units were able to reduce the need for boarding

or ambulance diversion, which means these were

able to alleviate access block and ED overcrowding.31

They also contribute to reduction in hospitalisation

and improvements in ambulatory care. In 2007, 1746

EDs in the US reported having observation units

and this constituted about 36% of the total number

of EDs.32 Among them, 56% were administratively

managed by ED staff. In the UK, Cooke et al3 also

reviewed the use of observation units and found

that they might reduce length of stay in the ED and

possibly in the hospital too. Nevertheless, the review

concluded that results of the studies were variable and

confounded by methodological issues. Experience in

an ED in Spain in 2009 showed

that opening of a 16-bed holding unit in the ED of

a 900-bed teaching hospital led to improvement in

access block.33 Observation units have also been shown

to play a role in selected clinical conditions, like

acute exacerbation of heart failure, which is known

to be a very common cause for hospital admission.34

Another condition in which observation units can

be helpful is acute pyelonephritis.35 A retrospective

cohort study was performed reviewing 633 patients

with pyelonephritis before and after the opening

of the observation unit. The proportion of patients

admitted to hospital from the ED decreased

significantly from 36% to 26% after the opening of

the observation unit.35

The functions and setup of these holding

units may differ from one institution to another. If

the setup is more like a short-stay ward or even an

in-patient ward, then its favourable effect on access

block may be attributed simply and chiefly from an

increase in the number of beds, as opposed to the

streamlining of management. In Hong Kong, the idea

of an ED observation unit is not new and many EDs,

including ours, have been running observation units

for the past 15 to 20 years. The difference is that,

over the past 3 to 4 years, many observation units

have been expanded with increased number of beds

and broader case-mix, and renamed as ‘Emergency

Medicine Wards’. For example, in our ED, the

20-bed observation unit was expanded to a 40-bed

Emergency Medicine Ward with introduction of

formal care protocols and pathways for managing

conditions such as congestive heart failure,

chronic obstructive airway diseases, deep venous

thrombosis, cellulitis, and pyelonephritis. From

our experience, we are skeptical if the Emergency

Medicine Ward has contributed significantly in

alleviating access block or ED overcrowding. This

ward has provided extra beds and obviously alleviated

some of the bed access problems. Therefore, it just

means that the duty and workload are shifted to

the ED with a cost involved, which includes space

and human resources at the minimum. Within the

holding unit context, further contributions over and

above this would require adherence to management

protocols that have been proven to safely reduce length of

stay or hospitalisation rates.

In Canada, Schull et al36 retrospectively

evaluated the effect of ED clinical decision units

on overall ED patient flow, comparing outcomes

(including length of stay, admission rate, etc)

between seven EDs which had implemented clinical

decision units and nine control EDs without clinical

decision units. They concluded that the benefits of

clinical decision units were just marginal and that

the potentials for gains in efficiency were limited.

In summary, there is some evidence for the

role of holding units for alleviating access block

and overcrowding but this needs to be incorporated

together with carefully planned clinical management

protocols and adequate support staff.

Early discharge and patient flow

In a recent study based on ED presentations, inpatient

admission, and discharge data from 23

hospitals in Queensland, Australia, it was shown

that during the days when ‘discharge peak’ lags behind

the peak in in-patient admissions, hospitals exhibit

increased levels of occupancy, in-patient and ED

length of stay, and increased access block.37 38

Initiatives directed at early in-patient discharges

would effectively mitigate the problem of ED

overcrowding and access block.

Since access block increases the clinical risk of

patients who might be deprived of timely attention,

assessment and management by various specialty

medical teams, considering earlier discharge of low-risk,

almost fully recovered in-patients in order to

create bed capacity for the incoming sick patients

would be an important principle worth putting into

practice, and for clinicians and managers to balance

the risks and benefits. This involves researching and

refining prediction rules to categorise the levels of

risk of discharging in-patients earlier.2 39 This process

is described as ‘reverse triage’, and described by Kelen

et al39 as to select patients who can be discharged

safely with little risk of serious consequence, in the

event of disasters that demand increased hospital bed

capacity. In 2012, an anecdotal report was published

describing how this reverse triage system was put

to effective use in an unexpected event resulting

in a sudden demand for beds.40 Although initially

described for use during disasters, this system is also

considered suitable even for everyday hospital use to

ensure safe management of hospital capacity or to

reduce access block.2 39

There is some evidence from a systematic

review of nine studies which showed that involving

social workers to support discharge of elderly

patients was able to reduce the readmission rate

within 6 to 12 months without apparent increase in

mortality. However, the effect on length of hospital

stay was uncertain.41 Expanding social work services

may help to prevent re-attendance, overcrowding,

and access block.

Discharge lounges are areas in the hospital

for patients to wait until transport and other

administrative discharge arrangements are

completed. A study found that after the introduction

of such lounges, there can be substantial savings in

bed hours (early discharge and reduced length of

stay).42 However, further studies focusing more on

economic evaluations are needed. In hospital wards,

delay in discharges may also be associated with

attitudes of staff members who think that quicker

discharges would result in more admissions, and

hence increased workload. Incentives and reward

programmes to motivate in-patient staff members

to speed up the discharge process are therefore

important.

Some studies have shown that modelling

methods using patient flow systems or bed

management techniques may improve the flow of

patients by identifying bottlenecks and key factors

driving access block. For example, Martin et al43

found that the greatest source of delay in patient

flow was the waiting time from an admission request

for bed to the actual time of exit from the ED for

admission. Some researchers have developed a

mathematical model using the ED census to predict

crowding, daily surge and operational efficiency, the

basic pattern of the ED census comprising input,

throughput and output.44 King et al45 showed that

through the application of “lean thinking” and by

process mapping followed by identification of value

streams in the ED, they were able to significantly

improve waiting times and length of stay in EDs.

Strategies can also be focused on addressing demand

on in-patient beds by gathering predictable data on

daily or weekly peaks and valleys, and be able to

distribute admissions more smoothly and evenly

across the weeks.2 46

Political action—management and resource priority

One logical and clear solution for managing access

block is to increase bed capacity, increase the number

of acute beds and corresponding staff strength in

the hospitals. In reality, this is an issue of resource

availability and prioritising, a problem which the

hospital management constantly grapples with, in an

attempt to find the best balance. Therefore, health

care institutional funders need to be convinced

that ED overcrowding and access block are issues

of significant importance compared to other areas

of health care, in which resource distribution is

also needed. Ultimately, when all other solutions

fail simply because the root cause of the problem is

a system capacity matter, then effective responses

need to come from the institutional and system-wide

level to increase capacity. There are many

avenues and methods by which the attention of

the government and health authority can be drawn

to help focus on increasing the number of acute

hospital beds and thereby reducing access block.

Health care professionals can press for changes by

taking collective actions, organising information

campaigns, lobbying, drawing attention of the

press and media, negotiations, and even by public

demonstrations.

The review by Moskop et al2 presented an

anecdotal report of an information campaign

conducted by doctors in Canada that effectively

influenced changes in the government funding

policies.47 In April 2005, emergency physicians at

Vancouver General Hospital, frustrated by their

ongoing failure to persuade hospital administration

to address their access block crisis, gave selected

patients a statement expressing their “non-confidence

in the ability of the Vancouver General

Hospital ED to provide safe, timely, and appropriate

emergency medical care.”47 Emergency physicians

at other hospitals in Vancouver expressed similar

concerns publicly.47 As a result of this campaign, the

provincial Ministry of Health injected significant

funding to address the problem during that period.47

In order to relieve access block, governments

can also set targets and performance measures for

hospitals and the most well known among them is the

4-hour rule introduced by the UK NHS in 2004.48 By

this measure, 98% of ED patients are to be seen and

either admitted, discharged, or transferred within 4

hours from the time of triage. This makes hospital

administration take more responsibility for the

problem of access block, which becomes a ‘hospital-wide issue’ rather than purely an ED problem. As a

result, emergency care was prioritised, government

funding was increased, facilities were upgraded,

and more staff employed in order that hospital EDs

can achieve the target.48 Before implementation of

the 4-hour rule, as many as 23% of patients waited

longer than 4 hours in the ED, but the 2007 statistics

show that 97.7% patients were assessed, treated, and

discharged within 4 hours.48 49 In 2009 in Perth, the

Western Australian government also introduced a

similar 4-hour rule for hospitals, whereby initially

85% and eventually 98% of patients presenting

to the ED should be either discharged home or

admitted into hospital within 4 hours.50 A study was

performed by retrieving hospital and patient data

which looked at outcome measures like mortality

rates, access block, and overcrowding rates pre-

and post-introduction of the 4-hour rule.50 It was

found that reversal of overcrowding coincided with

significant improvements in mortality rate in three

tertiary hospitals in which the rule was introduced.50

Although targets are intended to improve the quality

of care, sometimes patient care can be compromised

in order to meet stringent time targets, as seen with

Mid Staffordshire NHS Trust in the UK which was

reported to have neglected clinical needs and safety

of patients in order to achieve time targets.48 In 2011,

the 4-hour target in England was replaced by other

clinical indicators.

Limitations

Due to differences in health systems, some of the

solutions discussed in the Hong Kong perspective

may be less practicable in other countries. For

example, in some countries the number of primary

care physicians from the public system available

to participate in ED work may be limited; and the

private practitioners may generally be less motivated

to provide part-time services.

Conclusion

Several possible strategies and management

approaches effective in dealing with the complex

problem of access block and ED overcrowding in

hospitals have been identified and discussed. Some

of these solutions have been developed for many

years and are supported by current evidence, while

others are promising, warranting more detailed

investigation. The strategy to co-locate primary

care in the ED is worth evaluating more, the extent

of the benefits being dependent on the relative

predominance of ‘primary care attendance’ as a

cause of ED overcrowding, and the availability of GPs

or other primary care providers in the workforce.

Further development of fast-track or minor injury

units, the use of ‘see and treat’ strategies, and further

training of more ENPs are also important directions

to take. Holding units have been quite extensively

studied and there is some evidence for their role,

although these need to be incorporated together with

well-planned management protocols and adequate

staff support. ‘Reverse triage’ is a relatively new

concept and needs to be well formulated. Prediction

rules to select patients who can be discharged safely

with little risk of serious consequences have been

derived and can be used in the event of vast surges

in demand for hospital bed capacity. This may be

applicable for accelerating discharge of patients

safely in times of access block.

References

1. Moskop JC, Sklar DP, Geiderman JM, Schears RM,

Bookman KJ. Emergency department crowding, part 1—concepts, causes, and moral consequences. Ann Emerg

Med 2009;53:605-11. Crossref

2. Moskop JC, Sklar DP, Geiderman JM, Schears RM,

Bookman KJ. Emergency department crowding, part 2—barriers to reform and strategies to overcome them. Ann

Emerg Med 2009;53:612-7. Crossref

3. Cooke M, Fisher J, Dale J, et al. Reducing attendances and

waits in emergency departments. A systematic review of

present innovations. London: The National Coordinating

Centre for the Service Delivery and Organisation, London

School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine; 2004.

4. Forero R, McCarthy S, Hillman K. Access block and

emergency department overcrowding. Available from:

http://ccforum.com/content/15/2/216. Accessed 1 Feb

2013.

5. Dunn R. Reduced access block causes shorter emergency

department waiting times: An historical control

observational study. Emerg Med 2003;15:232-8. Crossref

6. Forero R, Hillman KM, McCarthy S, Fatovich DM, Joseph

AP, Richardson DB. Access block and ED overcrowding.

Emerg Med Australas 2010;22:119-35. Crossref

7. Gilligan P, Winder S, Ramphul N, O’Kelly P. The referral

and complete evaluation time study. Eur J Emerg Med

2010;17:349-53. Crossref

8. Bullard MJ, Villa-Roel C, Bond K, Vester M, Holroyd B,

Rowe B. Tracking emergency department overcrowding in

a tertiary care academic institution. Healthc Q 2009;12:99-106. Crossref

9. Richardson D. 2008 – 2. Access block point prevalence

survey. The Australasian College for Emergency

Medicine 2008. Available from: https://www.acem.org.au/getattachment/e6442562-06f7-4629-b7f9-8102236c8b9d/Access-Block-2009-point-prevalence-study.aspx. Accessed

1 Feb 2013.

10. Sun BC, Hsia RY, Weiss RE, et al. Effect of emergency

department crowding on outcomes of admitted patients.

Ann Emerg Med 2013;61:605-11.e6. Crossref

11. Kilcoyne M, Dowling M. Working in an overcrowded

accident and emergency department: nurses’ narratives.

Aust J Adv Nurs 2007;25:21-7.

12. Bartlett S, Fatovich D. Emergency department patient

preferences for waiting for a bed. Emerg Med Australas

2009;21:25-30. Crossref

13. Jelinek GA, Weiland TJ, Mackinlay C. Supervision and

feedback for junior medical staff in Australian emergency

departments: findings from the emergency medicine

capacity assessment study. BMC Med Educ 2010;10:74. Crossref

14. Rajpar SF, Smith MA, Cooke MW. Study of choice between

accident and emergency departments and general practice

centres for out of hours primary care problems. J Accid

Emerg Med 2000;17:18-21. Crossref

15. Bianco A, Pileggi C, Angelillo IF. Non-urgent visits to a

hospital emergency department in Italy. Public Health

2003;117:250-5. Crossref

16. Murphy AW. ‘Inappropriate’ attenders at accident and

emergency departments I: definition, incidence and

reasons for attendance. Fam Pract 1998;15:23-32. Crossref

17. Gill JM, Reese CL 4th, Diamond JJ. Disagreement among

health care professionals about the care needs of emergency

department patients. Ann Emerg Med 1996;28:474-9. Crossref

18. Roberts E, Mays N. Accident and emergency care at

the primary-secondary interface: a systematic review

of the evidence on substitution. London: King’s Fund

Commission; 1997.

19. Dale J, Lang H, Roberts JA, Green J, Glucksman E.

Cost effectiveness of treating primary care patients in

accident and emergency: a comparison between general

practitioners, senior house officers, and registrars. BMJ

1996;312:1340-4. Crossref

20. Gibney D, Murphy AW, Smith M, Bury G, Plunkett PK.

Attitudes of Dublin accident and emergency department

doctors and nurses towards the services offered by local

general practitioners. J Accid Emerg Med 1995;12:262-5. Crossref

21. Krakau I, Hassler E. Provision for clinic patients in the ED

produces more nonemergency visits. Am J Emerg Med

1999;17:18-20. Crossref

22. Yoon P, Steiner I, Reinhardt G. Analysis of factors

influencing length of stay in the emergency department.

CJEM 2003;5:155-61.

23. Sanchez M, Smally AJ, Grant RJ, Jacobs LM. Effects of a

fast-track area on emergency department performance. J

Emerg Med 2006;31:117-20. Crossref

24. Rodi SW, Grau MV, Orsini CM. Evaluation of a fast

track unit: alignment of resources and demand results

in improved satisfaction and decreased length of stay for

emergency department patients. Qual Manag Health Care

2006;15:163-70. Crossref

25. O’Brien GM, Shapiro MJ, Woolard RW, O’Sullivan PS,

Stein MD. “Inappropriate” emergency department use:

a comparison of three methodologies for identification.

Acad Emerg Med 1996;3:252-7. Crossref

26. Kwa P, Blake D. Fast track: has it changed patient care in the

emergency department? Emerg Med Australas 2008;20:10-5. Crossref

27. Neades BL. Expanding the role of the nurse in the Accident

and Emergency department. Postgrad Med J 1997;73:17-22. Crossref

28. Carter AJ, Chochinov AH. A systematic review of the

impact of nurse practitioners on cost, quality of care,

satisfaction and wait times in the emergency department.

CJEM 2007;9:286-95.

29. Dinh M, Walker A, Parameswaran A, Enright N. Evaluating

the quality of care delivered by an emergency department

fast track unit with both nurse practitioners and doctors.

Australas Emerg Nurs J 2012;15:188-94. Crossref

30. Chung J, Way R, Rainer TH. Development of an emergency

nurse practitioner service in Hong Kong through

international collaboration: evaluation of the service

development. 1st Global Conference on Emergency

and Trauma Care; 2014 Sep 18-21; Dublin, Ireland. Int

Emerg Nurs 2014;22:237-60. Available from: http://www.internationalemergencynursing.com/article/S1755-599X(14)00280-8/fulltext. Accessed 6 Nov 2014.

31. Institute of Medicine Committee on the Future of

Emergency Care in the United States Health System.

Hospital-based emergency care: At the Breaking Point

(2007). Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2006.

Available from: http://www.nap.edu/catalog/11621.html. Accessed 15 Feb 2013.

32. Wiler JL, Ross MA, Ginde AA. National study of

emergency department observation services. Acad Emerg

Med 2011;18:959-65. Crossref

33. Gómez-Vaquero C, Soler AS, Pastor AJ, Mas JR, Rodriguez

JJ, Virós XC. Efficacy of a holding unit to reduce access block

and attendance pressure in the emergency department.

Emerg Med J 2009;26:571-2. Crossref

34. Collins SP, Schauer DP, Gupta A, Brunner H, Storrow AB,

Eckman MH. Cost-effectiveness analysis of ED decision

making in patients with non-high-risk heart failure. Am J

Emerg Med 2009;27:293-302. Crossref

35. Schrock JW, Reznikova S, Weller S. The effect of an

observation unit on the rate of ED admission and discharge

for pyelonephritis. Am J Emerg Med 2010;28:682-8. Crossref

36. Schull MJ, Vermeulen MJ, Stukel TA, et al. Evaluating the

effect of clinical decision units on patient flow in seven

Canadian emergency departments. Acad Emerg Med

2012;19:828-36. Crossref

37. Khana S, Boyle J, Good N, Lind J. Early discharge and its

effect on ED length of stay and access block. In: Meader

AJ, Matin-sanchez FJ, editors. Health informatics:

building a healthcare future through trusted information.

Amsterdam: IOS Press; 2012: 92-8.

38. Khana S, Boyle J, Good N, Lind J. Unravelling relationships:

Hospital occupancy levels, discharge timing and

emergency department access block. Emerg Med Australas

2012;24:510-7. Crossref

39. Kelen GD, Kraus CK, McCarthy ML, et al. Inpatient

disposition classification for the creation of hospital surge

capacity: a multiphase study. Lancet 2006;368:1984-90. Crossref

40. Satterthwaite PS, Atkinson CJ. Using ‘reverse triage’ to

create hospital surge capacity: Royal Darwin Hospital’s

response to the Ashmore Reef disaster. Emerg Med J

2012;29:160-2. Crossref

41. Hyde CJ, Robert IE, Sinclair AJ. The effects of supporting

discharge from hospital to home in older people. Age

Ageing 2000;29:271-9. Crossref

42. Cowdell F, Lees B, Wade M. Discharge planning. Armchair

fan. Health Serv J 2002;112:28-9.

43. Martin M, Champion R, Kinsman L, Masman K.

Mapping patient flow in a regional Australian emergency

department: a model driven approach. Int Emerg Nurs

2011;19:75-85. Crossref

44. Flottemesch TJ, Gordon BD, Jones SS. Advanced statistics:

developing a formal model of emergency department

census and defining operational efficiency. Acad Emerg

Med 2007;14:799-809. Crossref

45. King DL, Ben-Tovim DI, Bassham J. Redesigning emergency

department patient flows: application of Lean Thinking to

health care. Emerg Med Australas 2006;18:391-7. Crossref

46. Litvak E, Buerhaus PI, Davidoff F, Long MC, McManus

ML, Berwick DM. Managing unnecessary variability in

patient demand to reduce nursing stress and improve

patient safety. Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf 2005;31:330-8.

47. Abu-Laban RB. The junkyard dogs find their teeth:

addressing the crisis of admitted patients in Canadian

emergency departments. CJEM 2006;8:388-91.

48. Letham K, Gray A. The four-hour target in the NHS

emergency departments: a critical comment. Emergencias

2012;24:69-72.

49. Department of Health (UK). Hospital waiting times

and waiting lists. 2010. Available from: http://webarchive.nationalarchives.gov.uk/20100406182906/http://www.dh.gov.uk/en/Publicationsandstatistics/Statistics/Performancedataandstatistics/HospitalWaitingTimesandListStatistics/index.htm. Accessed 1 Mar 2013.

50. Geelhoed GC, de Klerk NH. Emergency department

overcrowding, mortality and the 4-hour rule in Western

Australia. Med J Aust 2012;196:122-6. Crossref