Hong Kong Med J 2015 Apr;21(2):124–30 | Epub 10 Mar 2015

DOI: 10.12809/hkmj144292

© Hong Kong Academy of Medicine. CC BY-NC-ND 4.0

ORIGINAL ARTICLE

Comparison of efficacy and tolerance of short-duration open-ended ureteral catheter drainage and tamsulosin administration to indwelling double J stents following ureteroscopic removal of stones

Vikram S Chauhan, MB, BS, MS (Surgery)1;

Rajeev Bansal, MB, BS, MS (Surgery)1;

Mayuri Ahuja, MB, BS, DGO2

1 School of Medical Sciences & Research, Sharda University, Greater

Noida (U.P.) 201306, India

2 Kokila Dhirubhai Ambani Hospital & Medical Research Institute, Andheri West, Mumbai 400053, India

Corresponding author: Dr Vikram S Chauhan (vsing73@rediffmail.com)

Abstract

Objectives: To evaluate the efficacy of short-duration, open-ended ureteral catheter drainage as a replacement to indwelling stent, and to study the effect of tamsulosin on stent-induced pain and storage symptoms following uncomplicated ureteroscopic removal of stones.

Design: Prospective randomised study.

Setting: School of Medical Sciences and Research, Sharda University, Greater Noida, India.

Patients: Patients who underwent ureteroscopic removal of stones for lower ureteral stones between November 2011 and January 2014 were randomly assigned into three groups. Patients in group 1 (n=33) were stented with 5-French double J stent for 2 weeks. Patients in group 2 (n=35) were administered tablet tamsulosin 0.4 mg once daily for 2 weeks in addition to stenting, and those in group 3 (n=31) underwent 5-French open-ended ureteral catheter drainage for 48 hours.

Main outcome measures: All patients were evaluated for flank pain using visual analogue scale scores at days 1, 2, 7, and 14, and for storage (irritative) bladder symptoms using International Prostate Symptom Score on days 7 and 14, and for quality-of-life score (using International Prostate Symptom Score) on day 14.

Results: Of the 99 patients, visual analogue scale scores were significantly lower for groups 2 and 3 (P<0.0001). The International Prostate Symptom Scores for all parameters were lower in patients from groups 2 and 3 compared with group 1 both on days 7 and 14 (P<0.0001). Analgesic requirements were similar in all three groups.

Conclusion: Open-ended ureteral catheter drainage is equally effective and better tolerated than routine stenting following uncomplicated ureteroscopic removal of stones. Tamsulosin reduces storage symptoms and improves quality of life after ureteral stenting.

New knowledge added by this

study

- This study shows that short-duration (up to 48 hours) ureteral drainage following ureteroscopic removal of stones (URS) has better efficacy and tolerance than indwelling stent placement with respect to the need for postoperative drainage. Hence, this can be a replacement for double J stenting.

- Routine tamsulosin administration in patients with indwelling stents following URS has beneficial effects not only on irritative bladder symptoms but also on flank pain (both persistent and voiding).

- Replacement of stents with short-duration open-ended ureteral catheter drainage provides early and more rehabilitation to the patients following URS. This is a viable option because there is no need for follow-up for stent-related symptoms, or maintaining records for planning its removal (no lost or retained stents).

- It avoids a second invasive endoscopic procedure of stent removal, thereby reducing the medical and financial burden on the patient (especially important in developing countries). Patients are more likely to undergo URS again if required in the future (with stone recurrence) than opt for less effective or expensive choices like medical management, shock wave lithotripsy, or alternative forms of medicine.

- In stented patients, tamsulosin administration improves the overall quality of life, and makes the period with stent in situ more bearable and asymptomatic.

Introduction

Ureteroscopic removal of stones (URS) is the

standard endoscopic method for treatment of lower

ureteric calculi. In recent times, this procedure does

not require routine dilatation of ureteric orifice due

to the availability of small-calibre rigid ureteroscopes

that can be easily manipulated into the ureter in

most of the cases.

Once the stones are removed, an indwelling

ureteral double J stent is placed which remains in

situ postoperatively for a period of 2 to 4 weeks.

This is dependent on a variety of factors such as the

difficulty in removal of stones, any mucosal injury,

and associated stricture of the ureter or its meatus.

Finney1 was the first to describe the use of double J

stents in the year 1978.2 The use of stents has proved

to be beneficial as seen in various studies, because

they prevent or reduce the occurrence of ureteric

oedema, clot colic, and subsequent development

of secondary ureteric stricture in cases with

mucosal injury or difficult stones.3 4 5 However, the

use of ureteral stents is not without its attendant

complications. Patients may develop flank pain,

haematuria, clot retention, dysuria, frequency, and

other irritative bladder symptoms following stent

placement in the postoperative period. Hence,

many authors have questioned the need for routine

placement of stents or their early removal.6 Recently,

researchers have proposed that the irritative and

other symptoms due to stents can be reduced or

overcome by the use of alpha blockers.7 With this

background knowledge, we conducted a prospective

randomised study with the aim to assess the efficacy

of oral tamsulosin for 14 days following stenting, and

efficacy of an open-ended ureteral catheter for 48

hours instead of a stent as viable options in patients

who underwent uncomplicated URS for lower

ureteric stones.

Methods

This study was conducted at School of Medical

Sciences and Research, Sharda University, Greater

Noida, India, after obtaining due clearance from the

ethics committee. Recruitment of patients was done

over a period from November 2011 to January 2014

and included a total of 99 patients who underwent

URS for lower ureteric stones.

Inclusion criteria were lower ureteric stones

defined as those imaged below the lower border

of sacroiliac joint of up to 10 mm in diameter on

computed tomography. Stones larger than 10 mm

in diameter, presence of ipsilateral kidney stones,

cases with lower ureteric or meatal stricture

requiring dilatation, and cases which had significant

mucosal injury (flap formation) per-operatively were

excluded.

All patients underwent URS under spinal

anaesthesia using an 8-French rigid

ureteroscope, and stones requiring fragmentation

were broken with a pneumatic lithoclast and these

fragments were retrieved with forceps. One surgeon

performed all the interventional procedures during

the study period.

The patients were randomly assigned to three

groups using randomisation table. On the random

number table, we chose an arbitrary place to start

and then read towards the right of the table from

that number. We used a number read on the table

from 1 to 3 to assign cases to group 1, a number from

4 to 6 to assign to group 2, and a number from 7 to 9

to assign cases to group 3 (a value of 0 was ignored).

A duty doctor prepared 120 serially numbered slips

of papers (indicating the number of enrolment) by

following the above randomisation protocol and had

written in them the group to which a new case was

to be assigned. The chits were folded, stapled, and

stacked in a box and stored in the operating theatre.

After completion of the URS, the floor nurse opened

the chit to reveal the appropriate enrolment number

and the group (group 1, 2 or 3) to which the patient

would go, thereby deciding further intervention.

Patients in group 1 underwent double J stent

placement following URS for a period of 2 weeks.

Patients in group 2 were administered tablet

tamsulosin 0.4 mg once daily for 2 weeks in addition

to double J stent. Patients in group 3 underwent

placement of an open-ended 5-French ureteral catheter

following the URS procedure, the distal end of which

was introduced into the lumen of Foley catheter.

Both the ureteric and Foley catheter were removed

on the second postoperative day in group 3 patients.

A 5-French 25-cm double J stent was used for

stenting and the duration of surgery was recorded

as time from the introduction of ureteroscope to

the placement of Foley catheter. Postoperatively,

patients were assessed for flank pain (persistent

or voiding) by asking them to report the pain on

a visual analogue scale (VAS) of 0 to 10 (0 being

no pain and 10 pain as severe as it could be) on

postoperative days 1, 2, 7, and 14. Patients were

also asked to report storage symptoms using the

International Prostate Symptom Score (IPSS) at

1 and 2 weeks postoperatively to assess irritative

bladder symptoms, while the IPSS quality-of-life

index was assessed at 2 weeks postoperatively.

All stented patients were discharged with tablet

levofloxacin 250 mg orally once daily for 2 weeks as

suppressive prophylaxis for infection.

Patients who had an indwelling double

J stent underwent stent removal after 2 weeks

by cystoscopy under local anaesthesia using 2%

lidocaine jelly supplemented with intravenous

injection of pentazocine 30 mg on a patient-need

basis, and were asked to report the pain experienced

during the stent removal on a VAS. Administration

and reporting of VAS scores was done by the floor

manager (administrative personnel) with assistance

from nurse on duty for the in-patients (wards),

while an intern and nurse on duty for out-patients

on follow-up was done in local language (Hindi). All

of these staff assessing VAS were blinded and had

no direct influence or active role in the treatment or

assessment protocol.

All patients on completion of 2 weeks of surgery

were asked, “Whether you would opt for the same

procedure again as treatment if you develop ureteral

stones in the future?” Patients complaining of pain

postoperatively were given injection tramadol 50 mg

intravenously if needed. If pain persisted, patients

were given intravenous injection of pentazocine 30

mg. All patients underwent intravenous urography

after 1 month of procedure to document stone

clearance and development of ureteral stricture.

Patients were asked to report to the out-patient

department if any other complications occurred

following discharge.

The sample size was estimated with the

following logic. We assumed the margin of error

that could be accepted as 5%, with a confidence

level of 90% and population size of 45 (cases that

were admitted with flank pain and require URS for

stones), in our institution the number of cases who

undergo URS typically in a year would be roughly

around 45 to 50. Assuming the response distribution

to be 50%, with the above assumptions, the sample

size calculated was 39, using the following formula:

Sample size n and margin of error E are given by

x = Z(c/100)2r(100 - r)

n = N x/((N - 1)E2 + x)

E = Sqrt[(N - n)x/n(N - 1)]

where N is the population size, r is the fraction of responses that we are interested in, and Z(c/100) is the critical value for the confidence level c.

Sample size n and margin of error E are given by

x = Z(c/100)2r(100 - r)

n = N x/((N - 1)E2 + x)

E = Sqrt[(N - n)x/n(N - 1)]

where N is the population size, r is the fraction of responses that we are interested in, and Z(c/100) is the critical value for the confidence level c.

This calculation is based on the normal

distribution, and assumes that there are more than

30 samples and a power of 80. Hence, we chose to

recruit approximately 35 patients in each arm of

study.

Statistical analyses

After collation of data, Student’s t test and Pearson

Chi squared test were used to analyse the three

groups for age, sex, stone size, and operating time.

We also comparatively evaluated the severity of

flank pain on postoperative days 1, 2 and weeks 1

and 2, and the IPSS for each group regarding storage

symptoms, total IPSSs at postoperative weeks 1 and

2, and the quality-of-life index at 2 weeks. Results

from groups 2 and 3 were compared with group 1 to

draw conclusions. Fisher’s exact test and Pearson

Chi squared tests were used to compare the number

of patients who needed intravenous analgesics due

to severe postoperative pain and to examine the

response to our question, “Whether you would opt

for the same procedure again as treatment if you

develop ureteral stones in the future?”

Results

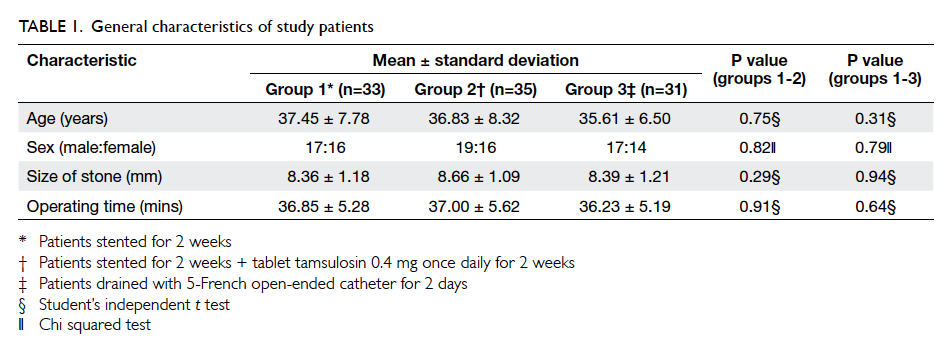

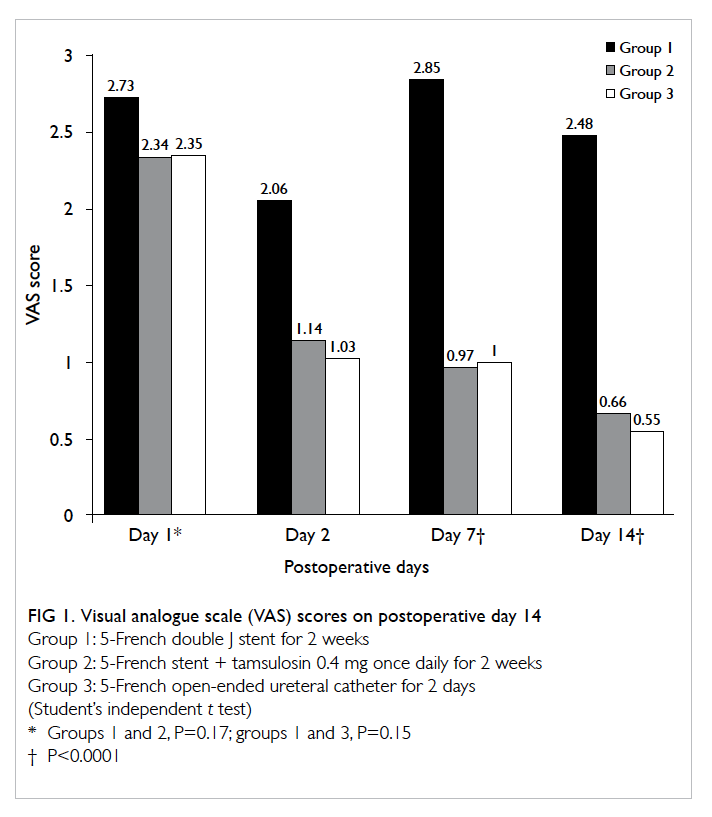

There was no significant variation in the three

groups with regard to variables like age, sex, stone

size, and operating time (Table 1). The VAS score for

flank pain, however, showed significant differences

among the three groups. On postoperative day 1, the

mean (± standard deviation) VAS scores in groups 1,

2, and 3 were 2.73 ± 1.14, 2.34 ± 1.12, and 2.35 ± 0.86

respectively, but were not statistically significant

(groups 1 and 2, P=0.17; groups 1 and 3, P=0.15).

On day 7, the mean VAS scores for groups 2 and 3

were 0.97 ± 0.77 and 1.00 ± 0.72 respectively, which

were significantly lower than group 1 score of 2.85 ±

1.52 (P<0.0001). On day 14, the mean VAS scores for

groups 1, 2, and 3 were 2.48 ± 1.40, 0.66 ± 0.67, and

0.55 ± 0.56 respectively (P<0.0001). This amounted

to significantly greater pain in group 1 patients as

compared with those in groups 2 and 3 (for groups 1-2

and 1-3, P<0.0001; Fig 1). Among those stented, the

mean VAS score for stent removal using 2% lidocaine

jelly was 3.76 ± 1.55 but the mean VAS score for stent

removal with regard to sex (male:female = 36:32) was

4.97 ± 0.80 and 2.41 ± 0.96, respectively and this was

statistically significant (P<0.0001).

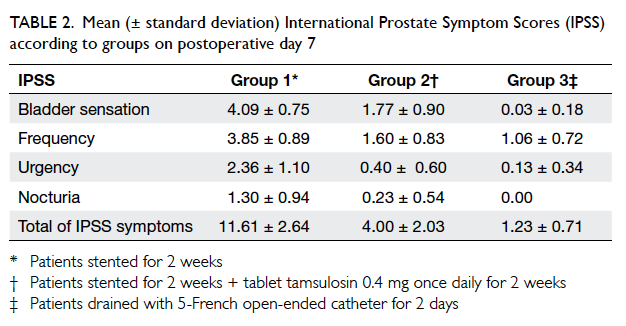

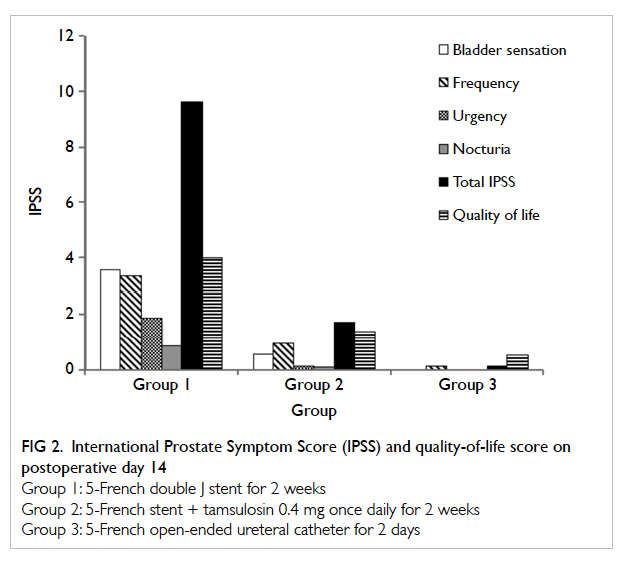

Analyses of IPSS on both postoperative days

7 and 14 for bladder sensation, frequency, urgency,

nocturia, and the sum total of IPSS showed there

was significant decrease in group 2 as compared with

group 1 for all four parameters (P<0.0001). Group

3 patients had minimal mean IPSS scores to begin

with (Table 2). The mean quality-of-life scores for

groups 1, 2, 3 were 4.00 ± 0.92, 1.37 ± 0.86, and 0.52

± 0.50 respectively, and this was significantly better

for groups 2 and 3 compared with group 1 (P<0.00001;

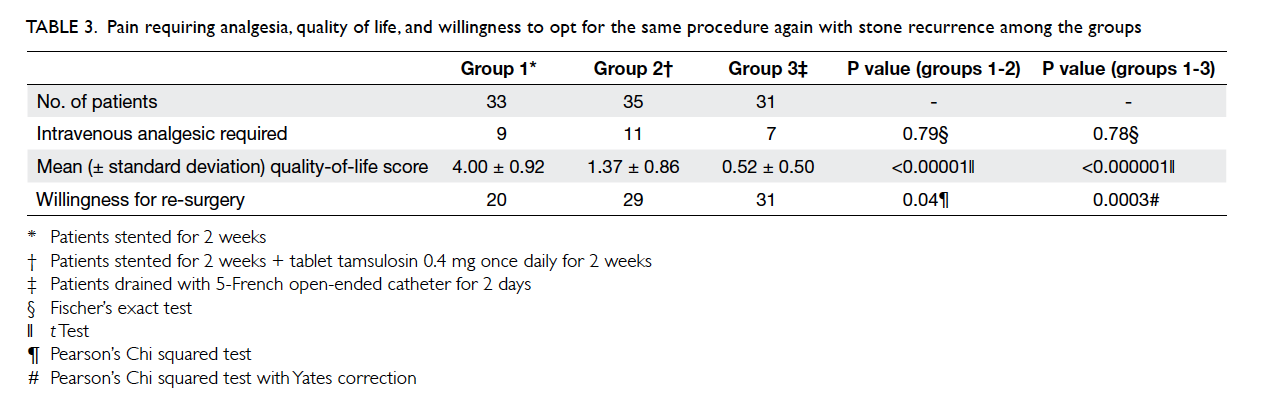

Fig 2 and Table 3).

Table 2. Mean (± standard deviation) International Prostate Symptom Scores (IPSS) according to groups on postoperative day 7

Figure 2. International Prostate Symptom Score (IPSS) and quality-of-life score on postoperative day 14

Table 3. Pain requiring analgesia, quality of life, and willingness to opt for the same procedure again with stone recurrence among the groups

Nine patients in group 1, 11 in group 2,

and seven in group 3 complained of pain requiring

injection of tramadol 50 mg (Table 3). Only

one patient (stent-only group) further required

intravenous injection of pentazocine 30 mg due to

persistent pain. No patient in any group required

intravenous analgesic after day 2 making analgesic

need similar in all groups. One patient who was

stented and had not received tamsulosin reported

gross haematuria on the sixth day, which required

readmission and catheterization with bladder wash,

and the haematuria responded to conservative

treatment. Beyond the 2-week period, no patient

reported any other complication during the 2-month

follow-up.

In this study, 20, 29, and all patients in groups

1, 2, and 3 respectively showed willingness for

undergoing same procedure in future if needed.

This showed that a higher percentage of patients

in groups 2 and 3 were willing for repeated surgery (if

needed) than in group 1, which was statistically

significant (for groups 1-2, P=0.04, and for groups

1-3, P=0.0003; Table 3). Two patients from the open

drainage group were lost to follow-up after 7 days.

There was no crossover from one group to the other

once assigned.

Discussion

Indwelling double J stents are routinely placed

following URS to prevent flank pain and secondary

ureteral strictures.4 8 9 However, duration-dependent

symptoms due to ureteral stents have been well

documented. Pollard and Macfarlane10 reported

stent-related symptoms in 18 (90%) out of 20 patients

who had indwelling ureteral stents following URS.

Bregg and Riehle11 reported that symptoms such

as gross haematuria (42%), dysuria (26%), and flank

pain (30%) appeared in stented patients prior to

being taken up for shock wave lithotripsy. Stoller et

al8 documented ureteral stent–related symptoms, like

flank pain, frequency, urgency, and dysuria, in at least

50% of patients who had an indwelling ureteral stent.

In a series by Han et al,12 haematuria was reported

as the most common symptom (69%) followed by

dysuria (45.8%), frequency (42.2%), lower abdominal

pain during voiding (32.2%), and flank pain (25.4%).

Most studies report that apart from urgency and

dysuria (which improve with time), there is no relief

in other symptoms till the stent is removed.

Wang et al7 showed that administration of α-blocker (tamsulosin) in stented patients improves flank pain and IPSS storage symptoms, along with an

overall improvement in quality of life. They reported

mean scores of frequency, urgency, nocturia as

3.7, 3.82, 2.01 in stented patients and 1.55, 1.43,

0.65 in those who received tamsulosin for 2 weeks,

respectively. The mean score of quality of life in IPSS

was 4.21 in stented group and 1.6 in stented + tamsulosin group. Moon et al13 reported that when compared

with stenting, all the storage categories of the IPSS

were significantly lower in the 1-day ureteral stent

group (P<0.01). Although the VAS scores were not

significantly different on postoperative day 1, it was

significantly lower in the 1-day ureteral catheter

group on postoperative days 7 and 14 (P<0.01).13

In our study, the mean total IPSS score at 2

weeks postoperatively was 9.64, 1.71, and 0.13 for

groups 1, 2, and 3 respectively (Fig 2). We also found

that the mean VAS scores for flank pain and the

mean IPSS scores of bladder sensation, frequency,

urgency, nocturia, were significantly higher in

patients in group 1 when compared with groups 2

and 3 (Figs 1 and 2). These findings suggest that the

indwelling double J stent causes time-dependent

pain and storage symptoms due to persistent

bladder irritation and administration of tamsulosin

did significantly decrease symptoms. Our patients

who received tamsulosin also fared much better

on the quality-of-life index at both 1 and 2 weeks

postoperatively than the group with stent placement

only (mean score, 1.37 and 4.00 respectively), while

those who underwent open-ended catheter drainage

showed minimal irritative symptoms (Table 2).

In addition, removal of indwelling stent

constitutes an additional procedure, which not only

is physical but also a financial burden to the patient

especially in a developing country like India. Kim

et al14 evaluated pain that occurred on cystoscopy

following an intramuscular injection of diclofenac

90 mg. The mean score of VAS during the procedure was

7.8 ± 0.7, which indicated severe pain. In

addition, only 22.5% of patients responded “yes” to

a questionnaire about their willingness to submit

to the same procedure again.14 Moon et al13 reported

a mean VAS score of 4.96 ± 1.29 for stent removal using

lidocaine gel. Although the mean VAS score for

stent removal under local anaesthesia in our series

was 3.76, the mean for males and females was 4.97

and 2.41, respectively. This amounts to moderately

severe pain in males, and in association with

irritative bladder symptoms that could influence the

patient’s willingness to go for a repeated procedure

in future if required. Besides, manipulation during

the procedure to remove the stent under local

anaesthesia especially in males could lead to urethral

or bladder injuries, a drawback that Hollenbeck et

al15 have observed.

Many have questioned the need for ureteral

stenting following URS. Denstedt et al16 in a series of

58 patients who underwent URS (29 stented and 29

non-stented) reported that there was no significant

difference in complications or success rates for URS

between stented versus non-stented cases. However,

Djaladat et al17 reported that when ureteroscopy

was performed without catheterization, flank pain

and renal colic could result from early ureteral

oedema implying that some postoperative drainage

is better than no drainage at all. This formed the

premise of using the open-ended ureteral catheter

in immediate postoperative period in our series and

the significantly lower VAS scores suggest that their

placement can be as effective as stents with minimal

irritative symptoms.17 Nabi et al18 concluded that

there was no significant difference in postoperative

requirements for analgesia, urinary tract infection,

the stone-free rate, or ureteric stricture formation

in patients who underwent uncomplicated URS.

There was no significant difference in analgesic

requirement in the three groups in our study; 9,

11, and 7 patients in groups 1, 2, and 3 respectively

required intravenous tramadol on postoperative days

1 and 2, only one patient in group 1 needed further

analgesia. No patient needed analgesics beyond the

second postoperative day which is comparable to

the series by Moon et al13 who reported that ratio

of patients who needed intravenous analgesics

because of severe postoperative flank pain was not

significantly different between stented and open-drainage

groups.

In our study, 20 out of 33 in group 1, 29 out

of 35 in group 2, and all 31 patients in group 3

responded affirmatively when asked “Whether you

would opt for the same procedure again as treatment

if you develop ureteral stones in the future?” The

P values for willingness for repeated procedure

were 0.04 and 0.0003 when comparing groups 1-2

and 1-3 respectively, which is in line with another

study (willingness P=0.02 in favour of open-ended

drainage).13 The results show that patients in groups

2 and 3 (tamsulosin and open-catheter drainage)

were significantly more likely to accept a repeated

procedure if needed. Hence, it can be inferred that

administration of tamsulosin following stenting or

placement of open-ended catheter (removed on day

2) was better tolerated by patients compared with an

indwelling stent–only procedure.

The relatively small sample size and being unblinded which was a likely placebo

effect in the tamsulosin group were the most obvious

limitations in our study. We believe that since in the stented

group patients were given tablet levofloxacin 250 mg

as suppressive prophylaxis post-discharge, any relief

in lower urinary tract symptoms therefore could

not be attributed to tamsulosin alone as placebo

effect. Assessment of VAS was done by personnel

who were blinded and had no direct influence on

the treatment or assessment protocol; this ruled out

surgeons’ bias and their involvement in influencing

the patient’s reporting of VAS scores. Degree of

difficulty, complexity, and duration of the procedure

could be construed as confounding factors in the

study. However, the relatively simple inclusion and

exclusion criteria which included all but the absolute

indications for stenting for comparison obviate this

and the results demonstrate that open-ended short-duration

ureteral drainage can replace stenting in all

other scenarios.

Conclusion

Accepting the limitations of a smaller sample size,

open-ended catheter drainage for 2 days is better

tolerated for flank pain and irritative bladder

symptoms when compared with an indwelling double J

stent for 2 weeks, without any significant difference

in complications or efficacy. We recommend this

procedure as a viable replacement to routine

stenting following URS. In those patients who do

undergo stenting following URS, administration

of tamsulosin significantly reduces stent-related

flank pain and irritative symptoms and enhances

the overall quality of life. In view of the possible

placebo effect on patients in group 2, the results

show that there is a need for more exhaustive and

larger multicentre randomised controlled trials to

assess the role of tamsulosin in countering post-URS stenting symptoms, given its wide acceptance

for pain relief and stone passage in treating lower

ureteral stones.

Declaration

No conflicts of interest were declared by authors.

References

1. Finney RP. Experience with new double J ureteral catheter

stent. J Urol 1978;120:678-81.

2. Hepperlen TW, Mardis HK, Kammandel H. Self-retained

internal ureteral stents: a new approach. J Urol

1978;119:731-4.

3. Lee JH, Woo SH, Kim ET, Kim DK, Park J. Comparison

of patient satisfaction with treatment outcomes between

ureteroscopy and shock wave lithotripsy for proximal

ureteral stones. Korean J Urol 2010;51:788-93. Crossref

4. Harmon WJ, Sershon PD, Blute ML, Patterson DE,

Segura JW. Ureteroscopy: current practice and long-term

complications. J Urol 1997;157:28-32. Crossref

5. Boddy SA, Nimmon CC, Jones S, et al. Acute ureteric

dilatation for ureteroscopy. An experimental study. Br J

Urol 1988;61:27-31. Crossref

6. Hosking DH, McColm SE, Smith WE. Is stenting following

ureteroscopy for removal of distal ureteral calculi

necessary? J Urol 1999;161:48-50. Crossref

7. Wang CJ, Huang SW, Chang CH. Effects of tamsulosin

on lower urinary tract symptoms due to double-J stent: a

prospective study. Urol Int 2009;83:66-9. Crossref

8. Stoller ML, Wolf JS Jr, Hofmann R, Marc B. Ureteroscopy

without routine balloon dilation: an outcome assessment. J

Urol 1992;147:1238-42.

9. Netto Júnior NR, Claro Jde A, Esteves SC, Andrade EF.

Ureteroscopic stone removal in the distal ureter. Why

change? J Urol 1997;157:2081-3. Crossref

10. Pollard SG, Macfarlane R. Symptoms arising from Double-J

ureteral stents. J Urol 1988;139:37-8.

11. Bregg K, Riehle RA Jr. Morbidity associated with

indwelling internal stents after shock wave lithotripsy. J

Urol 1989;141:510-2.

12. Han CH, Ha US, Park DJ, Kim SH, Lee YS, Kang SH.

Change of symptom characteristics with time in patients

with indwelling double-J ureteral stents. Korean J Urol

2005;46:1137-40.

13. Moon KT, Cho HJ, Cho JM, et al. Comparison of an

indwelling period following ureteroscopic removal

of stones between Double-J stents and open-ended

catheters: a prospective, pilot, randomized, multicenter

study. Korean J Urol 2011;52:698-702. Crossref

14. Kim KS, Kim JS, Park SW. Study on the effects and safety

of propofol anaesthesia during cytoscopy. Korean J Urol

2006;47:1230-5. Crossref

15. Hollenbeck BK, Schuster TG, Faerber GJ, Wolf JS Jr.

Routine placement of ureteral stents is unnecessary after

ureteroscopy for urinary calculi. Urology 2001;57:639-43. Crossref

16. Denstedt JD, Wollin TA, Sofer M, Nott L, Weir M, D’A

Honey RJ. A prospective randomized controlled trial

comparing nonstented versus stented ureteroscopic

lithotripsy. J Urol 2001;165:1419-22. Crossref

17. Djaladat H, Tajik P, Payandemehr P, Alehashemi S. Ureteral

catheterization in uncomplicated ureterolithotripsy: a

randomized, controlled trial. Eur Urol 2007;52:836-41. Crossref

18. Nabi G, Cook J, N’Dow J, McClinton S. Outcomes of

stenting after uncomplicated ureteroscopy: systematic

review and meta-analysis. BMJ 2007;334:572. Crossref