Hong Kong Med J 2014;20:139–44 | Number 2, April 2014 | Epub 14 Mar 2014

DOI: 10.12809/hkmj134134

© Hong Kong Academy of Medicine. CC BY-NC-ND 4.0

ORIGINAL ARTICLE

Public lacks knowledge on chronic kidney disease: telephone survey

KM Chow, MB, ChB, FRCP;

CC Szeto, MD, FRCP;

Bonnie CH Kwan, MB, BS, FRCP;

CB Leung, MB, ChB, FRCP;

Philip KT Li, MD, FRCP

Department of Medicine and Therapeutics, The Chinese University of Hong Kong, Prince of Wales Hospital, Shatin, Hong Kong

Corresponding author: Dr KM Chow (Chow_Kai_Ming@alumni.cuhk.net)

Abstract

Objectives: To examine knowledge of chronic

kidney disease in the general public.

Design: Cross-sectional telephone survey.

Setting: Hong Kong.

Participants: Community-dwelling adults who

spoke Chinese in Hong Kong.

Results: The response rate was 47.3% (516/1091)

out of all subjects who were eligible to participate.

The final survey population included 516 adults

(55.6% female), of whom over 80% had received a

secondary level of education or higher. Close to

20% of the participants self-reported a diagnosis of

hypertension. Few (17.8%) realised the asymptomatic

nature of chronic kidney disease. Less than half of

these individuals identified hypertension (43.8%) or

diabetes (44.0%) as risk factors of kidney disease.

Awareness of high dietary sodium as a risk factor for

chronic kidney disease was high (79.5%).

Conclusions: The public in Hong Kong is poorly

informed about chronic kidney disease, with

major knowledge gaps regarding the influence of

hypertension on kidney disease. We are concerned

about the public’s unawareness of hypertension

being a risk factor for kidney disease. Future health

education should target areas of knowledge deficits.

New knowledge added by this

study

- Despite the wealth of evidence for hypertension being a risk factor of chronic kidney disease, less than half the general public in Hong Kong are aware of the association.

- Only 17.8% of respondents in a telephone survey recognised the asymptomatic nature of chronic kidney disease.

- There is an urgent need for better public education focused on risk factors of chronic kidney disease, so as to improve the chance of opportunistic screening for kidney disease.

Introduction

Several recent surveys have documented low levels

of knowledge about chronic kidney disease among

patients.1 2 3 In a US survey of almost 400 patients at

all stages of chronic kidney disease not on dialysis,1

more than half reported no or little knowledge about

the symptoms of kidney disease, or medications that

can be harmful to the kidney. Furthermore, awareness

of chronic kidney disease in the community is low,

and limited knowledge about this disorder in the

general public poses an even more significant hurdle

in disease prevention. A large representative sample

of Chinese adults yielded a 10.8% prevalence of

chronic kidney disease, whereas only 12.5% of them

were aware they had this condition.4

Data on general public knowledge on chronic

kidney disease are essential to understanding

knowledge gaps and formulating education programmes. Without knowing knowledge gaps,

public health education programmes cannot

be planned in a strategic manner. To examine

knowledge on kidney disease and identify areas

of misconception in the general population, we

conducted a cross-sectional telephone survey in

Hong Kong. We anticipated that assessment of

knowledge gaps would be important to improve the

public education and has the potential of preventing

chronic kidney disease.5

Methods

Between 4 and 7 March 2013, we carried out

a telephone survey of adults in Hong Kong.

Respondents were required to be adults aged 18

years or older, and to speak Cantonese or Mandarin.

The sampling method entailed selecting telephone

numbers randomly from the latest Hong Kong Residential Telephone Directories (both Chinese

and English versions) as seed numbers. In order

to include unpublished telephone numbers, the

last two digits of the selected seed numbers were

replaced by two new and random digits generated by

computer. When telephone contact was established

successfully with a target household, only a person

aged 18 years or more was chosen for an interview.

When there was more than one eligible subject in

the household, only one was chosen for the survey

(by convenience).

As a result, a total of 11 600 telephone calls

were made, and 2659 families were successfully

contacted. Ineligible contacts included invalid lines,

non-residential lines, voice machines, facsimile

numbers, and language problems. Of those successfully

connected, 1383 cut the line before confirmation,

562 targeted persons refused the interview, 185

families had no eligible participant, and 13 were not

interviewed because the target participants were not

available. Finally, a total of 516 respondents were

successfully interviewed, yielding a response rate of

47.3% (out of the 1091 eligible families contacted).

Trained interviewers from Hong Kong

Institute of Asia-Pacific Studies administered the

survey by telephone, and each interview lasted

10 minutes. Participants were asked close-ended

questions on general knowledge about chronic

kidney disease. The survey domains and instrument

were developed to assess knowledge of the

respondents on the general function of the kidneys,

causes and symptoms of chronic kidney disease,

and management and treatment of kidney disease.

Some of the multiple-choice questions were refined and modified from a questionnaire previously tested

in Singapore.2 Pre-testing of the questionnaire

was carried out on members of the public through

focus group discussions. The questionnaire was

tested for face validity as well as content saturation.

The finalised questionnaire was administered to patients at primary care public medical centres in

persons with no known chronic kidney disease.2 We

also collected demographic information (age, sex,

education level, and self-reported health conditions)

from the respondents.

Statistical analyses were performed using the

Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (Windows

version 16.0; SPSS Inc, Chicago [IL], US). Numerical

data were expressed as mean ± standard deviation.

Percentages were compared by means of Fisher’s

exact test or Chi squared test. A two-tailed P value

of <0.05 was regarded as statistically significant.

Results

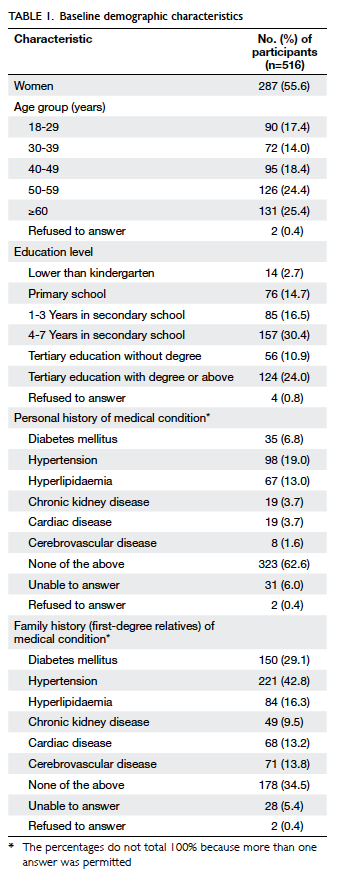

Table 1 lists the characteristics of the respondents,

who had a median age of 50 years. Over 80% of them

had received a secondary or higher level of education.

Only 3.7% (n=19) of the respondents were aware of

any personal history of chronic kidney disease, and

19.0% (n=98) admitted they had hypertension. A

family history of hypertension and diabetes was

reported in 42.8% and 29.1% of the respondents,

respectively.

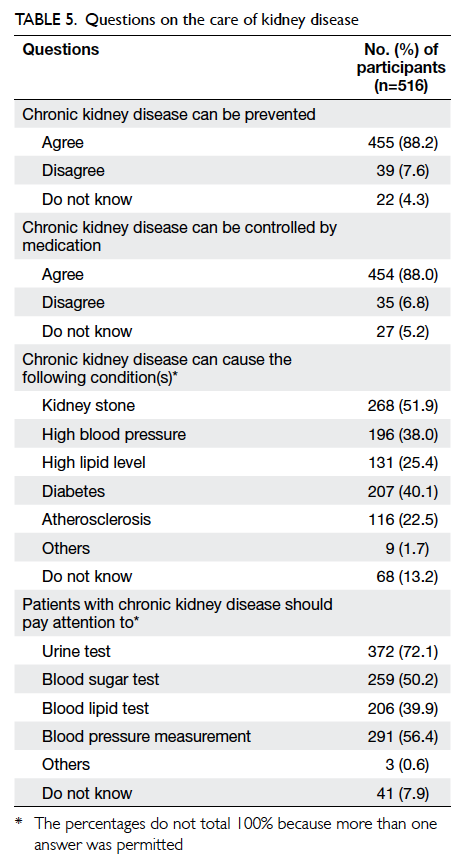

Table 2 lists the answers to questions on the

function of the kidneys and general knowledge on

kidney disease. Only 27.9% of the respondents knew

that only one kidney is needed for a human being

to lead a normal life, although most (84.7%) were

aware of the kidney’s function. Most respondents

(79.5%) listed high dietary sodium as a risk factor

for chronic kidney disease, but hypertension and

diabetes were selected less frequently. Less than half

of the respondents knew that hypertension (43.8%)

and diabetes (44.0%) can cause kidney disease, but

52.7% answered that frothy urine can be an early

manifestation of kidney disease. However, only

17.8% correctly identified the asymptomatic nature

of chronic kidney disease.

Table 2. Respondents’ general knowledge and perception on kidneys, causes of kidney diseases, and symptoms that might progress to kidney failure

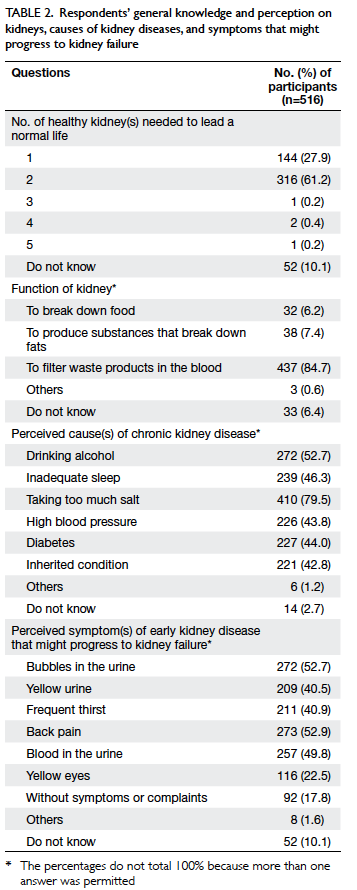

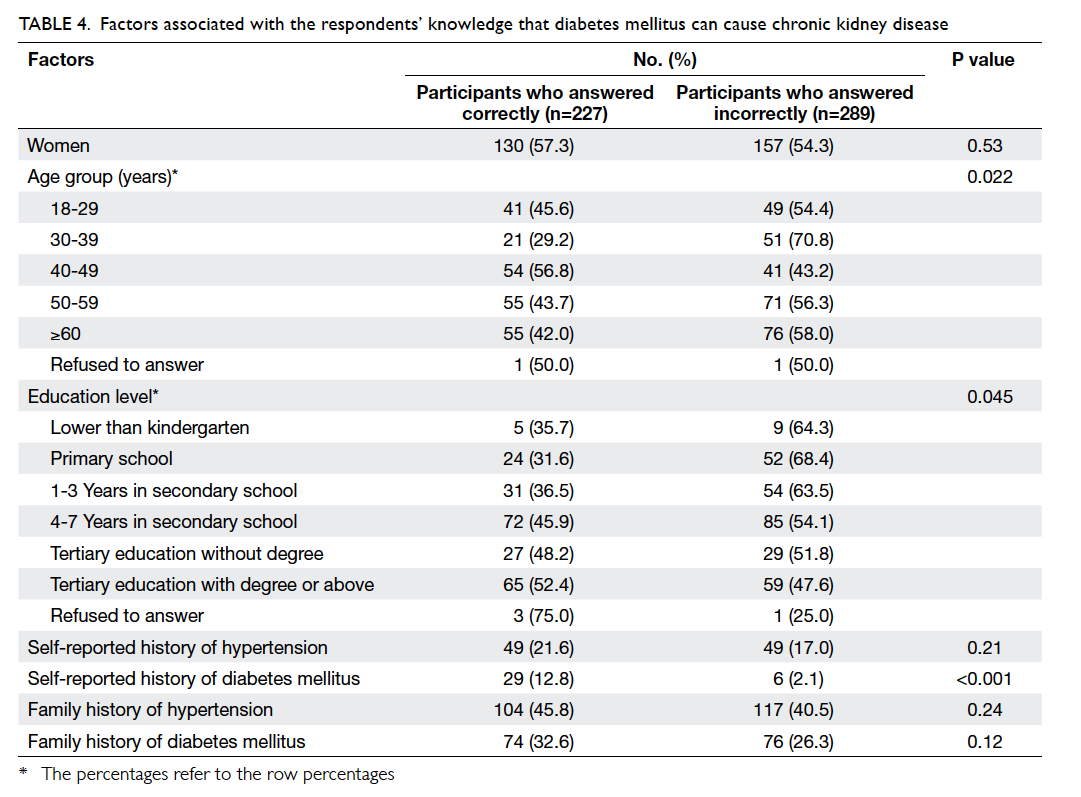

We further analysed factors that are associated

with a lack of knowledge that hypertension can cause

chronic kidney disease. There were no significant

differences between groups in terms of age and

gender. On the other hand, respondents with higher

levels of education were more likely to self-report

a personal or family history of hypertension and a

personal history of diabetes mellitus (Table 3), and

were more likely to know that hypertension is a

cause of kidney disease. Similarly, a higher education

level and a personal history of diabetes mellitus were

associated with better knowledge about the causal

relationship between diabetes and chronic kidney

disease (Table 4).

Table 3. Factors associated with the respondents’ knowledge that hypertension can cause chronic kidney disease

Table 4. Factors associated with the respondents’ knowledge that diabetes mellitus can cause chronic kidney disease

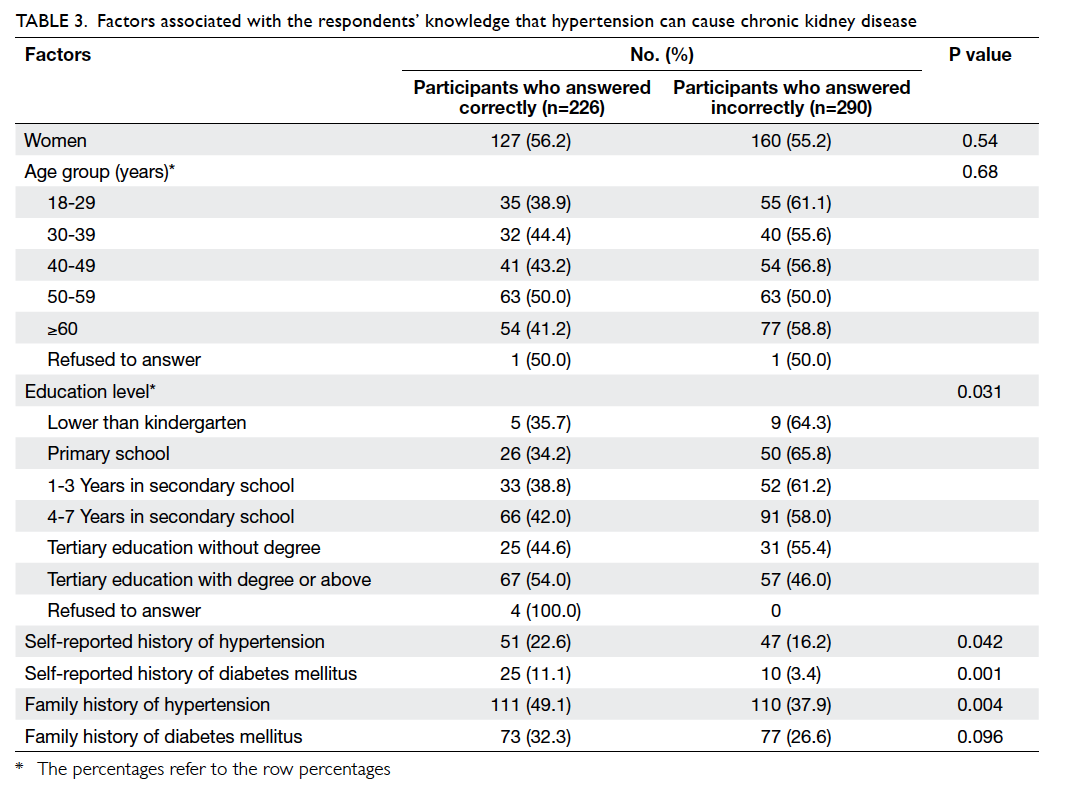

Table 5 shows the perceived sequelae of

chronic kidney disease. Overall, more than 80%

of respondents said that kidney disease could be

prevented, and could be controlled by medication.

On the other hand, over 60% of them did not identify

hypertension as a complication of chronic kidney disease. Furthermore, nearly half (43.6%) of the

subjects did not know the importance of checking

the blood pressure in patients with chronic kidney

disease, and less than a quarter (22.5%) believed

that chronic kidney disease can increase the risk of atherosclerosis.

Discussion

The main findings from this survey define the key

knowledge gaps concerning the kidney disease. In

particular, the public in Hong Kong is unfamiliar with

the relationship between hypertension and kidney

disease. Almost four in five knew that high dietary

sodium intake can be associated with kidney disease,

but the risk of hypertension causing kidney disease

was underestimated. Only 43.8% of respondents

considered hypertension as a factor that increases

the risk of kidney disease, and 43.6% did not perceive

the need for patients with kidney disease to have

blood pressure monitored. Another key issue was

that close to 20% of the respondents self-reported

a diagnosis of hypertension. Quantifying such

knowledge deficit indicates that high blood pressure

is relatively neglected and provides useful input for

future public education.

Low public awareness of hypertension as a cause of kidney damage has been demonstrated in

other national surveys. A cross-sectional survey

of 1435 primary care patients without kidney

disease in Singapore reported that only 51.2% knew

that chronic kidney disease could be caused by

diabetes, hypertension, and hereditary conditions.2

Overall, the public remains relatively unaware of

the two leading causes of chronic kidney disease

(hypertension and diabetes) in all developed and

many developing countries. Similar to hypertension,

the rising worldwide prevalence of diabetes and

the lack of knowledge about its relationship with

chronic kidney disease are of great concern.6 The

AusDiab study involving a survey of 852 Australian

subjects from the general population found an even

lower level of understanding of hypertension; 25.7%

of respondents reported poor diet as a cause of

kidney disease but only 2.8% identified hypertension

as risk factor.7 According to a cross-sectional survey

of 2017 African Americans, 12.1% knew that having

hypertension was a risk factor for kidney disease.8 A

strikingly prevailing theme among all these surveys

(including ours) was the tendency of the public

to name aspects of lifestyle instead of medical

conditions as risk factors for kidney disease. In other

words, there is relatively higher awareness of dietary

risk factors for kidney disease compared with high-risk

medical condition, notably hypertension. This

was affirmed in a community-based qualitative

exploratory analysis on kidney disease knowledge

among rural populations in the US.9 Analysis of the

audiotape scripts identified a representative theme:

lifestyle choices, such as drinking sodas and diet,

were routinely brought up as a means to explain the

occurrence of kidney disease.9

More accurate and prioritised knowledge of

kidney disease risk factors will lead to better disease

awareness and increase chances of opportunistic

screening. It is of concern that the general public

underestimates the importance of blood pressure

control. The most recent Global Burden of Disease

Study launched by the World Bank and the World

Health Organization announced that high blood

pressure has shifted from the fourth to the top risk

factor in terms of the global disability-adjusted

life-years.10 Inability to consider hypertension

as the risk factor for kidney disease implies that

many subjects perceive themselves at lower risk

of kidney disease, do not get screened, and have

less concern for certain health behaviours. In fact,

insufficient knowledge can drive the problem of

antihypertensive medication non-adherence, which

has recently been confirmed to confer an increased

risk of end-stage renal disease. Using the Canadian

health insurance databases of 185 476 patients with

hypertension, among those who were in possession

of their prescribed medication, more than 80% of the

time had a 33% lower risk of end-stage renal disease.11 Targeting health care professionals is probably not

the utmost concern, because only 3.4% of primary

care physicians failed to recognise hypertension

as a risk factor for chronic kidney disease according

to a cross-sectional representative survey of

primary care providers in the community.12 On the

other hand, targeting public education to prevent

asymptomatic renal disease should be explored.

We have previously confirmed a high frequency of

abnormal blood pressure readings and subclinical

urinalysis abnormalities (17.4%) in a screening

programme of 1201 apparently healthy community-dwelling

adults in Hong Kong.13 A successful public

educational programme should therefore aim at

better informing the asymptomatic nature of early

chronic kidney disease, and address the risk factors

such as hypertension. For this reason, the role of

hypertension in kidney disease was chosen as the

key message for World Kidney Day 2009.14

One important limitation of our survey

was that individual-level data of subjects who

declined the interview were missing. The fact that

we could not compare the baseline characteristics

of participants and those who declined raises the

possibility of response bias. Response bias implies

that the small percentage of subjects who responded

could have differed systematically from the majority

who did not answer telephone calls or cut the line

before confirmation. Moreover, the sample of

respondents in this residential telephone registry

may not be generalised to other populations, such

as those who mostly use mobile phones. Thus,

requirement of a landline telephone in order to be

sampled by the current random digit-dial telephone

survey raised the possibility of non-coverage bias.

Furthermore, our survey tool was not developed

through experts in health literacy and psychometric

analyses, and the questions were not field-tested

and validated. We are aware of better constructed

chronic kidney disease–specific knowledge survey

tools in other populations with known kidney

disease.15 Future research to assess kidney disease

knowledge in the Chinese community should follow

similar developments to improve the reliability and

validity of questionnaires. In addition, the diagnosis

of hypertension and chronic kidney disease in our

telephone survey respondents was not validated,

instead it was based entirely on self-reporting.

Conclusions

The general public in Hong Kong did not recognise

that the kidney is both a cause and victim of

hypertension. Public health education efforts that

target knowledge of kidney disease risk factors may

help reduce the burden of kidney disease.

Declaration

No conflicts of interest were declared by authors.

References

1. Wright Nunes JA, Wallston KA, Eden SK, Shintani AK, Ikizier TA, Cavanaugh KL. Associations among perceived and objective disease knowledge and satisfaction with physician communication in patients with chronic kidney disease. Kidney Int 2011;80:1344-51. CrossRef

2. Chow WL, Joshi VD, Tin AS, et al. Limited knowledge of chronic kidney disease among primary care patients—a cross-sectional survey. BMC Nephrol 2012;13:54. CrossRef

3. Tan AU, Hoffman B, Rosas SE. Patient perception of risk factors associated with chronic kidney disease morbidity and mortality. Ethn Dis 2010;20:106-10.

4. Zhang L, Wang F, Wang L, et al. Prevalence of chronic kidney disease in China: a cross-sectional survey. Lancet 2012;379:815-22. CrossRef

5. Collins AJ, Gilbertson DT, Snyder JJ, Chen SC, Foley RN. Chronic kidney disease awareness, screening and prevention: rationale for the design of a public education program. Nephrology (Carlton) 2010;15(Suppl 2):37-42. CrossRef

6. Jha V, Garcia-Garcia G, Iseki K, et al. Chronic kidney disease: global dimension and perspectives. Lancet 2013;382:260-72. CrossRef

7. White SL, Polkinghorne KR, Cass A, Shaw J, Atkins RC, Chadban SJ. Limited knowledge of kidney disease in a survey of AusDiab study participants. Med J Aust 2008;188:204-8.

8. Waterman AD, Browne T, Waterman BM, Gladstone EH, Hostetter T. Attitudes and behaviors of African Americans regarding early detection of kidney disease. Am J Kidney Dis 2008;51:554-62. CrossRef

9. Jennette CE, Vupputuri S, Hogan SL, Shoham DA, Falk RJ, Harward DH. Community perspectives on kidney disease and health promotion from at-risk populations in rural North Carolina, USA. Rural Remote Health 2010;10:1388.

10. Murray CJ, Lopez AD. Measuring the global burden of disease. N Engl J Med 2013;369:448-57. CrossRef

11. Roy L, White-Guay B, Dorais M, Dragomir A, Lessard M, Perreault S. Adherence to antihypertensive agents improves risk reduction of end-stage renal disease. Kidney Int 2013;84:570-7. CrossRef

12. Lea JP, McClellan WM, Melcher C, Gladstone E, Hostetter T. CKD risk factors reported by primary care physicians: do guidelines make a difference? Am J Kidney Dis 2006;47:72-7. CrossRef

13. Li PK, Kwan BC, Leung CB, et al. Prevalence of silent kidney disease in Hong Kong: the screening for Hong Kong Asymptomatic Renal Population and Evaluation (SHARE) program. Kidney Int Suppl 2005;94:S36-40. CrossRef

14. Bakris GL, Ritz E. The message for World Kidney Day 2009: hypertension and kidney disease: a marriage that should be prevented. Nephrology (Carlton) 2009;14:49-51. CrossRef

15. Wright JA, Wallston KA, Elasy TA, Ikizler TA, Cavanaugh KL. Development and results of a kidney disease knowledge survey given to patients with CKD. Am J Kidney Dis 2011;57:387-95. CrossRef