Hong Kong Med J 2014;20:126–33 | Number 2, April 2014 | Epub 14 Mar 2014

DOI: 10.12809/hkmj134076

© Hong Kong Academy of Medicine. CC BY-NC-ND 4.0

ORIGINAL ARTICLE

Public knowledge and attitudes towards cardiopulmonary resuscitation in Hong Kong: telephone survey

SY Chair, PhD1;

Maria SY Hung, DHSc, MN2;

Joseph CZ Lui, FHKCA, FHKAM (Anaesthesiology)3;

Diana TF Lee, PhD1;

Irene YC Shiu, MHA, MNurs (AdvPrac)4;

KC Choi, PhD1

1 The Nethersole School of Nursing, The Chinese University of Hong

Kong, Shatin, Hong Kong

2 School of Nursing, The Hong Kong Polytechnic University, Hunghom,

Hong Kong

3 United Christian Hospital, Hospital Authority, Hong Kong

4 Resuscitation Training Centre, Caritas Medical Centre, Shamshuipo,

Hong Kong

Corresponding author: Dr MSY Hung (maria.hung@polyu.edu.hk)

Abstract

Objectives: To investigate the public’s knowledge

and attitudes about cardiopulmonary resuscitation

in Hong Kong.

Design: Cross-sectional telephone survey.

Setting: Hong Kong.

Participants: Hong Kong residents aged 15 to 64

years.

Main outcome measures: The knowledge and

attitudes towards cardiopulmonary resuscitation.

Results: Among the 1013 respondents, only 214 (21%)

reported that they had received cardiopulmonary

resuscitation training. The majority (72%) of these

trained respondents had had their latest training

more than 2 years earlier. The main reasons for not

being involved in cardiopulmonary resuscitation

training included lack of time or interest, and “not

necessary”. People with full-time jobs and higher

levels of education were more likely to have such

training. Respondents stating they had received

cardiopulmonary resuscitation training were more

willing to try it if needed at home (odds ratio=3.3;

95% confidence interval, 2.4-4.6; P<0.001) and on

strangers in the street (4.3; 3.1-6.1; P<0.001) in case of

emergencies. Overall cardiopulmonary resuscitation

knowledge of the respondents was low (median=1,

out of 8). Among all the respondents, only four of them (0.4%) answered all the questions correctly.

Conclusions: Knowledge of cardiopulmonary

resuscitation was still poor among the public in

Hong Kong and the percentage of population

trained to perform it was also relatively low. Efforts

are needed to promote educational activities and

explore other approaches to skill reinforcement

and refreshment. Besides, we suggest enacting laws

to protect bystanders who offer cardiopulmonary

resuscitation, and incorporation of relevant training

course into secondary school and college curricula.

New knowledge added by this

study

- Knowledge of cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) is still poor among members of the Hong Kong public, and a relatively low percentage of the population has received relevant training.

- The Hong Kong government and non-government organisations need to promote educational activities and explore other approaches to reinforce and refresh participation in CPR.

- There is a need to enact laws to increase public awareness of CPR and protect bystanders who perform it.

- Incorporating CPR training into the secondary schools and colleges as part of a general education course is warranted.

Introduction

Out-of-hospital cardiac arrest is a public health

problem and leads to the highest proportion of

deaths in many parts of the world.1 2 According

to the American Heart Association (AHA), in the

US and Canada, approximately 350 000 people

per year suffer out-of-hospital cardiac arrests for

which cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) is

attempted.1 3 4 In Hong Kong, although no such

direct epidemiological information can be referred to, more than 1000 persons are believed to die

suddenly and unexpectedly each year; many of which

are presumed to be primarily due to cardiac arrests.5

For those who endure sudden cardiac arrests,

early, high-quality CPR can greatly improve chances

of survival.6 7 Nowadays, the importance of CPR is

well recognised and emphasised. Accordingly, the

AHA even recommended that CPR training and

familiarisation with automated external defibrillators

(AEDs) should be included in secondary school curricula.8 Thus, equipping the public with such skills

becomes one of the essential strategies to increase

the success of CPR for cardiac arrest victims.

In recent years, studies have been conducted

to examine the knowledge and attitude of the

public regarding CPR. In general, people had poor

knowledge on this subject and the proportion of

the public who had received the CPR training was

low.9 10 11 12 Besides, many individuals did not want to

perform cardiac compression with mouth-to-mouth

ventilation, due to fear of acquiring transmitted

diseases.13 These factors are likely to limit the numbers

of bystander CPRs carried out and contribute to

the low survival rates from out-of-hospital cardiac

arrests. A local study showed that for out-of-hospital

cardiac arrests, the frequency of bystander CPR was

only about 15.7% and the survival rate to eventual

discharge from hospital was as low as 1.3% in Hong

Kong.10

To identify effective measures to promote

CPR, the current situation should be evaluated.

This study aimed to explore the Hong Kong public’s

knowledge and attitudes about CPR. Its findings

could inform the community regarding preferences

to perform bystander CPR and more importantly it

could indicate directions for future training.

Methods

Population and data collection

This was a cross-sectional population-based survey. The study population comprised the

Chinese Hong Kong residents aged 15 to 64 years,

who speak Cantonese in domestic households.

Anonymous telephone interviews using a structured

questionnaire were conducted and launched in the

Telephone Survey Research Laboratory of the Hong

Kong Institute of Asia-Pacific Studies of The Chinese

University of Hong Kong. By using the Computer

Assisted Telephone Interviewing system, telephone

numbers were randomly selected from up-to-date

residential telephone directories that covered over

95% of Hong Kong households. The interviews were

conducted between 6:15 pm and 10:15 pm, to avoid

over-representing the non-working population. For

households with more than one eligible member,

the one whose birthday was closest to the interview

date was invited to join the study. At least three

attempts were made to contact individuals in any

given household. Such attempts were made at

different times of the day and/or different days

of the week, to avoid being labelled a non-contact

status (with an assigned number) so as to ensure

that survey results were not biased due to high non-contact/non-response rates. Eligible respondents

were briefed about the study and verbal consent

was sought. The study was approved by the Survey

and Behavioural Research Ethics Committee of The

Chinese University of Hong Kong.

Sample size

According to a previous study,11 12% of the population

had received CPR training. Owing to continuing

efforts and CPR promotion programmes/campaigns

by different associations and organisations in recent

years, it was expected that around 20% of the study

population had probably received prior CPR training.

Depending on the possible prevalence of subjects

with prior CPR training (ranging from 18 to 22%),

it was estimated that 883 to 1025 subjects would be

sufficient to estimate knowledge and attitudes with a

margin of error of ± 2.5% at 5% level of significance.

The sample size calculation was performed using

PASS 11 (NCSS, Kaysville [UT], US). Thus, we aimed

to recruit over 1000 subjects for this study.

Questionnaire

In this study we used a structured questionnaire,

which took about 5 to 10 minutes to complete, and was

developed in January 2010 (Appendix). It was based

on the 2005 AHA Guidelines for CPR and Emergency

Cardiovascular Care,14 Basic Life Support for

health care providers,15 and a review of the relevant

literature.11 12 It consisted of three sections. The first

entailed questions on demographics, including age,

gender, education level, occupation, family history

of heart disease, and ischaemic heart disease risk

factors. The second entailed questions about previous

CPR training. The third entailed questions on attitudes and knowledge regarding CPR. To evaluate

respondents’ relevant attitudes and knowledge,

questions were included about: willingness to

perform CPR (2 items), the basic knowledge related

to a victim’s response (1 item), management of

airway (2 items), breathing (2 items), circulation

(2 items), and AED usage (1 item). The anticipated

answers for the CPR knowledge questions (victim’s

response, management of airway, breathing, and

circulation) were consistent with information in

the latest AHA guidelines (2005 version). Content

validity was established by an expert panel including

four doctors and six nurses who were either AHA

Basic Life Support providers or instructors. The

content validity index rating item’s relevance to the

underlying construct was 0.96.

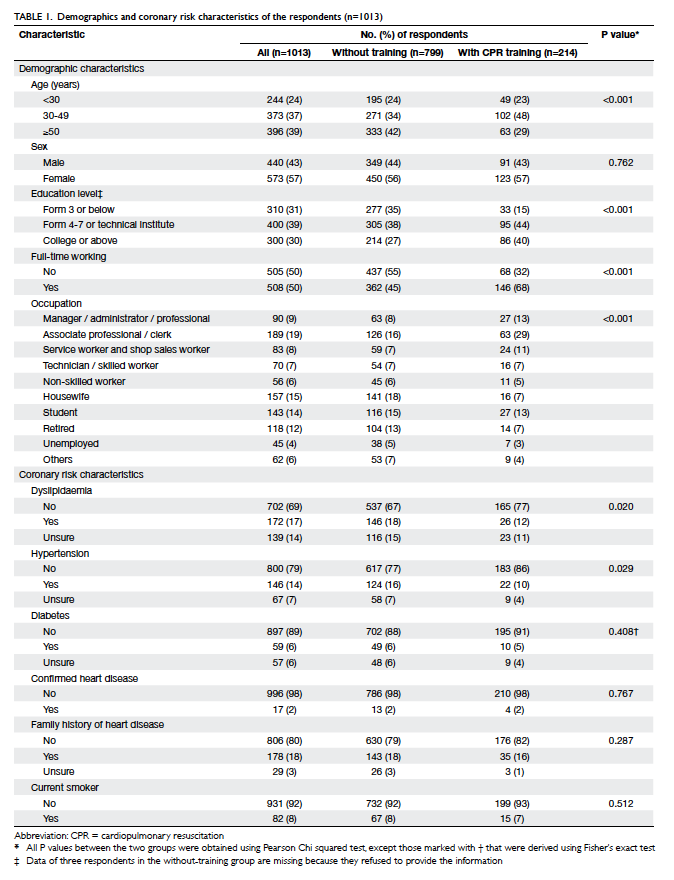

Statistical analyses

Data were categorised and presented in frequencies

(percentages). Univariate comparisons on

demographics and ischaemic heart disease risk

factors among those with and without CPR training

were conducted, using Pearson Chi squared or

Fisher’s exact tests, as appropriate. Logistic regression

analysis was used to identify demographics and

ischaemic heart disease risk factors (Table 1) that

were associated with CPR training. Variables

with a P value of <0.25 in the univariate analysis

were selected for use in the stepwise multivariate

logistic regression analysis, to delineate factors

independently associated with CPR training.16

Logistic regression models were also employed

to compare subjects with and without CPR training

with respect to various outcome variables (attitude

and knowledge about CPR), after adjustment for

demographics and coronary heart disease risk

factors. A ‘two-block stepwise’ logistic regression

modelling approach was used to make adjusted

comparisons of the two groups. The grouping factor

(CPR training: Yes/No) was first entered into logistic

regression model and then the demographics and

ischaemic heart disease risk factors (Table 1) were

entered in another block with stepwise selection.

In the final model, the adjusted odds ratio (OR)

to compare those with and without CPR training

(reference group) was derived, taking account of

demographics and ischaemic heart disease risk

factors. All statistical analyses were conducted using

SPSS 19.0 (Windows version 19.0; SPSS Inc, Chicago

[IL], US) with two-sided tests; a P value of <0.05 was

considered statistically significant.

Results

In this study, 2703 phone calls were not picked up

after three attempts, and 5669 calls were picked

up but 2735 calls were disconnected immediately

after knowing the purpose of the calls. A total of

2188 eligible respondents were identified, 1175 refused to participate. Finally, 1013 interviews were

conducted (response rate, 46%). The demographics

and ischaemic heart disease risk factors of these

respondents are shown in Table 1.

Cardiopulmonary resuscitation training

characteristics

Among the 1013 respondents, only 214 (21%)

reported that they had received CPR training;

the majority (72%, n=154) of whom had had their

latest training more than 2 years earlier. A large

proportion (63%, n=134) of the trained respondents

received their training via the Hong Kong St John

Ambulance (49%, n=104) and the Hong Kong Red

Cross (14%, n=30). Another 35 (16%) participants

had their training via their companies or workplaces. Their main reasons for taking CPR training

were ‘job requirement’ (48%, n=102) and ‘personal

interest’ (42%, n=90). For those who did not take

CPR training (n=799), most of them (74%, n=589)

claimed that they would not consider participating

in CPR training in the future. Reasons for not taking

CPR training could be multiple, and included ‘no

time’ (41%, n=241), ‘not necessary’ (26%, n=156), and

‘not interested’ (19%, n=110). In addition, 104 (18%)

participants picked ‘unable to learn CPR because of

their low education level or being too old’.

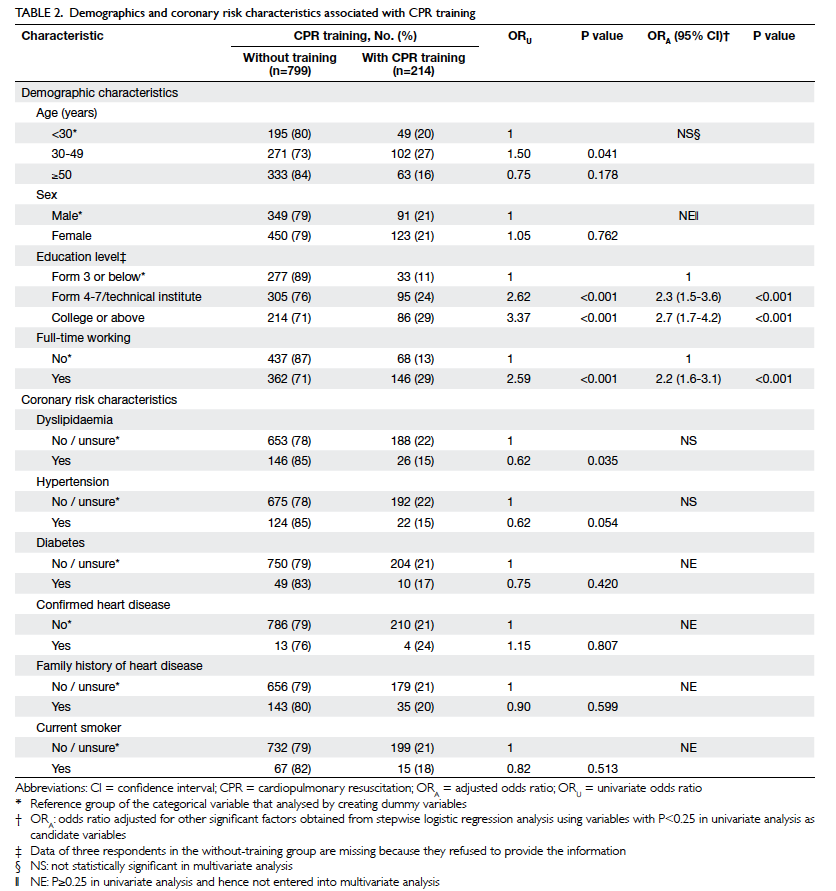

Factors associated with having

cardiopulmonary resuscitation training

Demographic and ischaemic heart disease risk

factors listed in Table 1 with a P value of <0.25 in

the univariate analysis were selected as candidate

variables for multivariate stepwise logistic

regression.16 Among them, age, education level,

full-time working status, occupation, having

dyslipidaemia and hypertension were associated

with having CPR training in the univariate analysis.

However, only having a full-time job (OR=2.2; 95%

confidence interval [CI], 1.6-3.1; P<0.001), middle

level education—Form 4-7/technical institute

(OR=2.3; 95% CI, 1.5-3.6; P<0.001), and a high level

of education—college or higher (OR=2.7; 95% CI,

1.7-4.2; P<0.001), were significantly associated with

having CPR training in the multivariate analysis.

Notably, having a low education level—Form 3 or

below—was not significantly associated with such

training (Table 2).

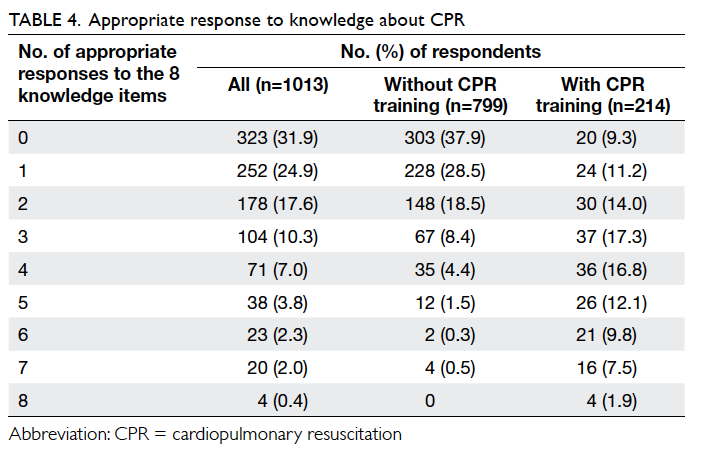

Willingness to perform cardiopulmonary

resuscitation

As shown in Table 3, the ratio of respondents with

and without training willing to attempt CPR on family

members at home was 72% vs 45% (P<0.001) and on

strangers in the street was 42% vs 15% (P<0.001).

Logistic regression analysis revealed that after

adjusting for potentially confounding demographic

and ischaemic heart disease risk factors, those with CPR training were also more likely to attempt CPR

at home (OR=3.3; 95% CI, 2.4-4.6; P<0.001) and

in the street (OR=4.3; 95% CI, 3.1-6.1; P<0.001) in

emergencies (Table 3).

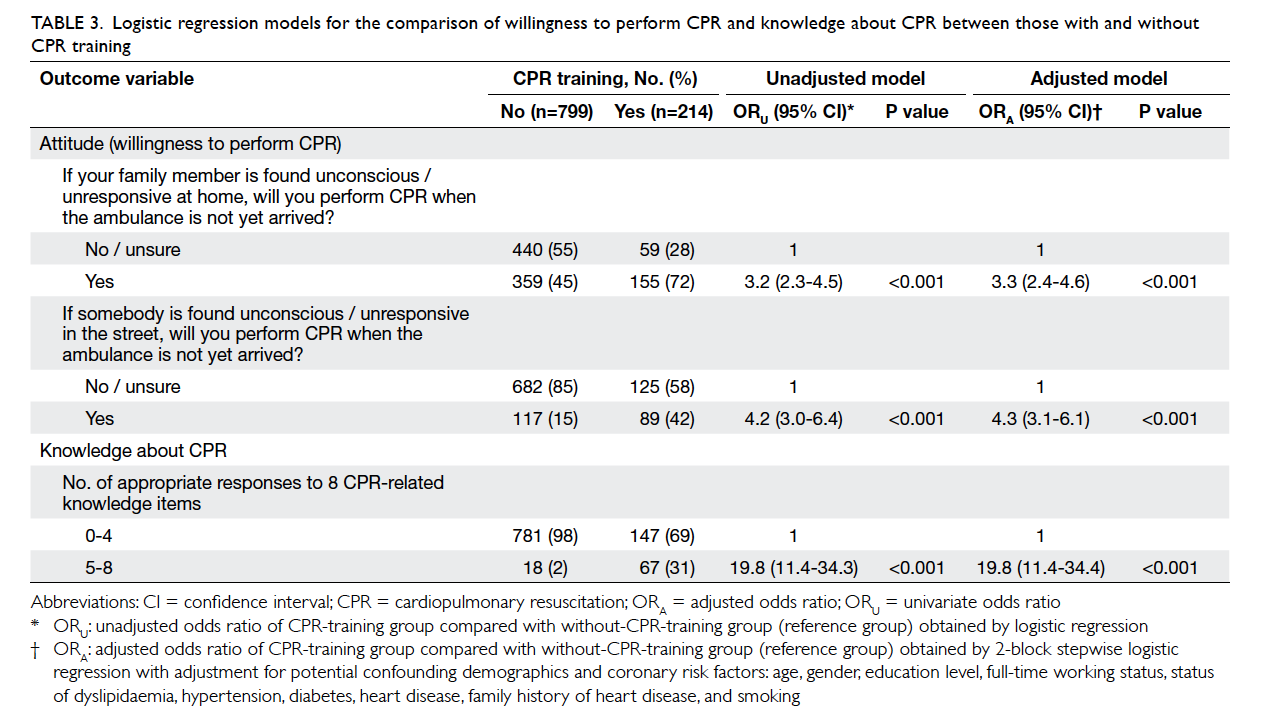

Knowledge on cardiopulmonary

resuscitation

Regarding knowledge on CPR, trained respondents were more likely to give correct responses to each

of the eight knowledge questions (all P<0.001). After

adjusting for potential confounding demographic

and ischaemic heart disease risk factors, logistic

regression showed that the trained group was

significantly more likely to give five or more

appropriate responses to the eight knowledge items

when compared with those without such training (OR=19.8; 95% CI, 11.4-34.4; P<0.001; Table 3).

Although the trained respondents achieved higher

scores on CPR knowledge (median=3) than those

who were untrained (median=1), the overall

CPR knowledge level of the respondents was low

(median=1). Among all the 1013 respondents, only

four (0.4%) answered all the questions correctly

(score=8), which also represented 1.9% of those who

had received CPR training (Table 4).

Table 3. Logistic regression models for the comparison of willingness to perform CPR and knowledge about CPR between those with and without CPR training

Discussion

The present study showed that 21% of the respondents had received CPR training, which was higher than in

a previous local study reporting 12%.11 Our rate was

comparable to data reported from elsewhere (27%

in New Zealand and 28% in Ireland),17 18 but much

lower than in reports from Australia (58%),19 Poland

(75%),20 and Washington (79%).21 Therefore, though

the trend for CPR training in Hong Kong seems to

be increasing, it seems far from sufficient, and the

majority had received their training more than 2

years earlier. Although it is commonly believed that

performing CPR without 100% accuracy is better

than doing nothing, whether our respondents could

perform appropriate CPR in an emergency was

questionable. In our cohort, skills appeared to have

deteriorated with time. One study suggested that

6-monthly reinstruction was needed to maintain

adequate CPR skills22; the 2-year intervals noted

in this study were much longer than what has

been suggested. Thus, after their first training, it is

suggested that individuals should attend refresher

courses. Moreover, the training institutions should pay more attention to remind the trainees on

the need for such reinstruction and updates.

The main reasons of taking CPR training were

“job requirement” and “personal interest”, which

were similar to reasons given in a previous study

from Ireland.18 Therefore, the workplace might

be considered a preferred place to conduct CPR

training in conjunction with government and non-government

organisations; in Hong Kong, these include St John Ambulance, the Hong Kong Red

Cross, and the Auxiliary Medical Services. In fact,

promoting CPR training in workplace seems an

important strategy, as 16% of trained respondents in

this study had already received such training in their

workplaces, and this was also in line with the results

of a study by Jennings et al.18

In this study, most non-trained respondents

would not consider receiving CPR training, giving

the following reasons: “no time”, “not necessary”, or

“not interested”. Lack of time for CPR training is a

common reason reported in different studies.11 23 24

To address this problem, self-instruction, such as via

video or internet training, may be considered. Studies

have shown that video self-instruction training

was as good as traditional classroom training,25 26

which is not only cost-effective but also flexible

compared to formal classroom training. In addition,

as recommended by the AHA,8 CPR training could

be incorporated into general education in secondary

schools. Several studies have investigated knowledge

and attitude towards CPR training, its feasibility

and the impact of CPR or life-supporting first-aid

training in primary and secondary schools in various

countries (Austria, Japan, and Norway) and reported

a positive experience.27 28 29 Either as part of the regular

curriculum, as mandatory courses, or as an elective

extra-curricular activity, it could be beneficial to

the students and the general public. By providing

students with CPR training, the first part of the chain

of survival in out-of-hospital cardiac arrest could

be enhanced for future generations, and increase

survival after sudden cardiac arrest. To successfully

carry out such a health and education policy, the

Hong Kong SAR Government can learn from other

Asian countries like Japan and Singapore, which

have already gained experience in CPR education for

secondary schools.

Those with full-time jobs and with higher levels

of education were more likely to attend CPR training,

which corresponded with the results of previous

studies.11 18 Not surprisingly 48% of respondents

in the present study were required to attend their

CPR training in connection with their jobs, while

18% believed that they were unable to learn as they

were too old or their level of education was too low.

Accordingly, this misunderstanding about CPR

needs correcting, and certainly CPR training should

be made available to those who are not employed.

Community centres could be used as possible

teaching venues to promote CPR, in conjunction

with the Hong Kong SAR Government and other

health care organisations (Hospital Authority, Hong

Kong Red Cross, and St John Ambulance). These

health-related organisations could play critical roles

in publicising the importance of CPR, and provide

accessible trainings for the public. Encouragingly, the Resuscitation Council of Hong Kong was established in 2012, and has the power to promote high standards

of training and public awareness on resuscitation.

In this study, respondents with CPR training

were more willing to perform it at home and in the

street (under emergency situations), presumably

as they had acquired enough knowledge and skills

to generate confidence and courage. The powerful

impact of CPR training on saving lives should

never be underestimated. Although only 15% of

the respondents without CPR training would like

to save others’ lives, nearly half of them (45%)

expressed willingness to perform CPR for their

family members if needed. The intimate relationship

among family members may be the motivation in

such cases. According to the AHA, 80% of sudden

cardiac arrests happen at home.7 Therefore, it makes

sense to exploit intimate emotions to facilitate and

publicise the CPR training, especially for those with

vulnerable members in their family.

In this study, the overall level of CPR

knowledge of the respondents was very low, with a

median of one correct answer out of eight questions,

which was in agreement with previous studies.11 20

Knowledge was particularly weak related to the

compression-to-ventilation ratio and appropriate

number of cardiac compressions per minute. This

could be because 79% of the respondents had not

received any CPR training, whereas 72% out of the

214 who had, recalled receiving it more than 2 years

earlier and 51% had received it more than 5 years

earlier. The AHA recommends its frequently revised

CPR guidelines based on rigorous scientific evidence

and the consensus opinions of experts. Using a

compression-to-ventilation ratio of 30:2 during

CPR for victims of all ages was a major update in

2005.30 In addition, the sequence of ‘A-B-C’ (Airway,

Breathing, Chest compression) was changed to

‘C-A-B’ (Chest compression, Airway, Breathing) in

the 2010 Guidelines.30 Therefore, knowledge about

up-to-date guidelines is likely to be most rewarding.

This survey did not explore why people

refused to perform CPR, which could be crucial

for raising bystander CPR rates in Hong Kong. As

indicated in one study from Japan, people had fear of

contracting transmitted diseases through mouth-to-mouth

ventilations.13 Legal liability could be another

concern. Therefore, public education and laws to

protect CPR providers appear necessary, for which

Good Samaritan laws need to be enacted. Certainly,

the reasons why Hong Kong citizens opt not to

undertake CPR warrant future surveys.

Conclusions

Knowledge of CPR in the Hong Kong public is still

poor. The percentage of citizens that have had CPR

training is relatively low. Unwillingness to perform

CPR is particularly common, especially among

those who have not received any CPR training. Government and non-government organisations

need to promote educational activities and explore

diverse approaches to reinforce and refresh the

content of training. Government needs to increase

public awareness of CPR and enact laws to protect

bystanders undertaking CPR. Incorporating CPR

training into the secondary school and college

curricula has also been suggested.

Declaration

The authors declare that there is no conflict of

interest.

Acknowledgement

The study was supported by the Nethersole School

of Nursing, Cardiovascular and Acute Care Research

Group Funding.

References

1. Travers AH, Rea TD, Bobrow BJ, et al. Part 4: CPR

Overview, 2010 American Heart Association Guidelines

for Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation and Emergency

Cardiovascular Care. Circulation 2010;122(18 Suppl 3):S676-84.

2. Roger VL, Go AS, Lloyd-Jones DM, et al. Heart disease and

stroke statistics—2012 update: A report from the American

Heart Association. Circulation 2012;125:e2-e220. CrossRef

3. Nichol G, Thomas E, Callaway CW, et al. Regional variation in out-of-hospital cardiac arrest incidence and outcome. JAMA 2008;300:1423-31. CrossRef

4. Chan PS, Jain R, Nallmothu BK, Berg RA, Susson C. Rapid response teams: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Arch Intern Med 2010;170:18-26. CrossRef

5. Lee K. The Hong Kong College of Cardiology automated external defibrillator programme. The Hong Kong Medical Diary 2008;13:14-6.

6. Sasson C, Rogers MA, Dahl J, Kellermann AL. Predictors of survival from out-of-hospital cardiac arrest: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes 2010;3:63-81. CrossRef

7. Hazinski MF, Nolan JP, Billi JE, et al. Part 1: executive summary: 2010 international consensus on cardiopulmonary resuscitation and emergency cardiovascular care science with treatment recommendations. Circulation 2010;122(16 Suppl 2):s250-75. CrossRef

8. Cave DM, Aufderheide TP, Beeson J, et al. Importance and implementation of training in cardiopulmonary resuscitation and automated external defibrillation in schools: a science advisory from the American Heart Association. Circulation 2011;123:691-706. CrossRef

9. Wong TW, Yeung KC. Out-of-hospital cardiac arrest: two and a half years experience of an accident and emergency department in Hong Kong. J Accid Emerg Med J 1995;12:34-9. CrossRef

10. Leung LP, Wong TW, Tong HK, Lo CB, Kan PG. Out-ofhospital cardiac arrest in Hong Kong. Prehosp Emerg Care 2001;5:308-11. CrossRef

11. Cheung BM, Ho C, Kou KO, et al. Knowledge of cardiopulmonary resuscitation among the public in Hong Kong: telephone questionnaire survey. Hong Kong Med J 2003;9:323-8.

12. Konstandions HD, Evangelos KI, Stamatis K, Thyresia S, Zacharenia AD. Community cardiopulmonary resuscitation training in Greece. Res Nurs Health 2008;31:165-71. CrossRef

13. Taniguchi T, Omi W, Inaba H. Attitudes toward the performance of bystander cardiopulmonary resuscitation in Japan. Resuscitation 2007;75:82-7. CrossRef

14. American Heart Association. 2005 American Heart Association Guidelines for Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation and Emergency Cardiovascular Care. Part 3: overview of CPR. Circulation 2005;112:s12-8.

15. Hazinski MF, Gonzales L, O'Neill L, editors. BLS for healthcare providers: student manual. Dallas, TX: American Heart Association; 2006.

16. Hosmer DW, Lemeshow S. Applied logistic regression. 2nd ed. New York: John Wiley and Sons; 2000. CrossRef

17. Larsen P, Pearson J, Galletly D. Knowledge and attitudes towards cardiopulmonary resuscitation in community. N Z Med J 2004;117:U870.

18. Jennings S, Hara TO, Cavanagh B, Bennett K. A national survey of prevalence of cardiopulmonary resuscitation training and knowledge of the emergency number in Ireland. Resuscitation 2009;80:1039-42. CrossRef

19. Celenza T, Gennat HC, O'Brien D, Jacobs IG, Lynch DM, Jelinek GA. Community competence in cardiopulmonary resuscitation. Resuscitation 2002;55:157-65. CrossRef

20. Rasmus A, Czekajlo MS. A national survey of the Polish population's cardiopulmonary resuscitation knowledge. Eur J Emerg Med 2000;7:39-43. CrossRef

21. Sipsma K, Stubbs BA, Plorde M. Training rates and willingness to perform CPR in King Country, Washington: a community survey. Resuscitation 2011;82:564-7. CrossRef

22. Berden HJ, Willems FF, Hendrick JM, Pijls NH, Knape JT. How frequently should basic cardiopulmonary resuscitation training be repeated to maintain adequate skills? BMJ 1993;306:1576-7. CrossRef

23. Liu H, Clark AP. Cardiopulmonary resuscitation training for family members. Dimens Crit Care Nurs 2009;28:156-63. CrossRef

24. Blewer AL, Leary M, Decker CS, et al. Cardiopulmonary resuscitation training of family members before hospital discharge using video self-instruction: a feasibility trial. J Hosp Med 2011;6:428-32. CrossRef

25. Einspruch EL, Lynch B, Aufderheide TP, Nichol G, Becker L. Retention of CPR skills learned in a traditional AHA Heart-saver course versus 30-min video self-training: A controlled randomized study. Resuscitation 2007;74:476-86. CrossRef

26. Chung CH, Siu AY, Po LL, Lam CY, Wong PC. Comparing the effectiveness of video self-instruction versus traditional classroom instruction targeted at cardiopulmonary resuscitation skills for laypersons: a prospective randomised controlled trial. Hong Kong Med J 2010;16:165-70.

27. Uray T, Lunaer A, Ochsenhofer A, et al. Feasibility of lifesupporting first-aid (LSFA) training as a mandatory subject in primary schools. Resuscitation 2003;59:211-20. CrossRef

28. Hamasu S, Morimoto T, Kuramoto N, et al. Effects of BLS training on factors associated with attitude toward CPR in college students. Resuscitation 2009;80:359-64. CrossRef

29. Kanstad BK, Nilsen SA, Fredriken K. CPR knowledge and attitude to performing bystander CPR among secondary school students in Norway. Resuscitation 2011;82:1053-9. CrossRef

30. Field JM, Hazinski MF, Sayre MR, et al. Part 1: executive summary: 2010 American Heart Association Guidelines for Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation and Emergency Cardiovascular Care. Circulation 2010;112(18 Suppl 3): S640-56. CrossRef