Hong Kong Med J 2014;20:102–6 | Number 2, April 2014

DOI: 10.12809/hkmj134065

© Hong Kong Academy of Medicine. CC BY-NC-ND 4.0

ORIGINAL ARTICLE

Live birth rate, multiple pregnancy rate, and obstetric outcomes of elective single and double embryo transfers: Hong Kong experience

Joyce Chai, FHKAM (Obstetrics and Gynaecology);

Tracy WY Yeung, FHKAM (Obstetrics and Gynaecology);

Vivian CY Lee, FHKAM (Obstetrics and Gynaecology);

Raymond HW Li, FHKAM (Obstetrics and Gynaecology);

Estella YL Lau, PhD;

William SB Yeung, PhD;

PC Ho, MD, FHKAM (Obstetrics and Gynaecology);

Ernest HY Ng, MD, FHKAM (Obstetrics and Gynaecology)

Department of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, Queen Mary Hospital, The

University of Hong Kong, Pokfulam, Hong Kong

Corresponding author: Dr J Chai (jchai@hkucc.hku.hk)

Abstract

Objective: To compare the live

birth rate, multiple pregnancy rate, and obstetric

outcomes of elective single and double embryo

transfers.

Design: Case series with internal comparisons.

Setting: University affiliated hospital, Hong Kong.

Participants: Between October 2009 and December

2011, 206 women underwent their first in-vitro

fertilisation cycle. Elective single embryo transfer

was offered to women who were aged 35 years or

below, and had endometrial thickness of 8 mm or

more and at least two embryos of good quality.

Main outcome measures: Live birth rate, multiple

birth rate, and obstetric outcomes.

Results: Among the 206 eligible women, 74

underwent an elective single embryo transfer and

132 a double embryo transfer. The live birth rate was

comparable in the two groups, being 39.2% in the

elective single embryo transfer group and 43.2% in

the double embryo transfer group, while the multiple

pregnancy rate was significantly lower in the elective

single embryo transfer group than the double embryo

transfer group (6.9% vs 40.4%; P<0.001). Gestational

ages and birth weights were comparable in the two groups. There was no significant difference between

the two groups with respect to the rate of preterm

delivery and antenatal complications (27.6% vs

43.9%, respectively; P>0.05).

Conclusion: In this selected population, an elective

single embryo transfer policy decreases the multiple

pregnancy rate without compromising the live birth

rate. The non-significant difference in antenatal

complications may be related to the small sample

size.

New knowledge added by this

study

- Elective single embryo transfer decreased the multiple pregnancy rate without compromising the live birth rate in women with a good prognosis undergoing in-vitro fertilisation.

- Elective single embryo transfer should be offered to women with a good prognosis and the care provider should promote this policy through education.

Introduction

In-vitro fertilisation (IVF) treatment is an effective

treatment for various causes of infertility and

involves development of multiple follicles after

ovarian stimulation, oocyte retrieval, and embryo

transfer after fertilisation. Historically, multiple

embryos were transferred to compensate for low

rates of implantation for individual embryos as well

as to achieve higher pregnancy rates. Consequently,

IVF carried a high risk of multiple pregnancy and its

associated adverse effects on mothers and children.1 In 2003 the Chairman of the European Society of

Human Reproduction and Embryology (ESHRE) commented that

assisted reproduction techniques should result in the

birth of one healthy child and that a twin pregnancy

should be regarded as a complication.2

In January 2013, the “Code of Practice on

Reproductive Technology & Embryo Research”

issued by the Council on Human Reproductive

Technology of Hong Kong stipulated that no more

than three embryos should be placed in a woman

in any one cycle.3 In August 2001, the Human Fertilisation and Embryology Authority in the UK

recommended reducing the number of embryos that

should be transferred in a single IVF treatment cycle

from three to two.4

In 2001, ESHRE recommended elective single

embryo transfer (eSET) for women aged under

34 years at the time of their first attempt, as soon

as they had obtained a top-quality embryo.5 In

2008, the British Fertility Society, in conjunction

with the Association of Clinical Embryologists,

introduced guidelines for eSET in the UK that aimed

to reduce IVF multiple pregnancy rates to less than

10%.6 Meta-analyses have shown that in a selected

population, compared with double embryo transfer

(DET), eSET could reduce multiple pregnancy rates

significantly, without compromising cumulative

pregnancy rates.7 8

Our centre offered eSET to eligible women in

order to reduce the multiple pregnancy rate. The

aim of this study was to compare the live birth rate,

multiple pregnancy rate, and obstetric outcomes

after eSET and DET in mothers having their first IVF/intra-cytoplasmic sperm injection (ICSI) attempt.

Methods

This was a retrospective study carried out at the

Centre of Assisted Reproduction and Embryology,

Queen Mary Hospital, The University of Hong Kong,

Hong Kong. Clinical details of all treatment cycles were prospectively entered into a computerised

database, and checked for correctness and

completeness on a regular basis. For this study, data

were retrieved for analysis and ethics committee

approval was deemed not necessary for retrospective

analysis of data.

Patients

In our programme, a maximum of two embryos were

replaced, irrespective of the woman’s age. Women

were eligible for eSET if they were ≤35 years of age

at the time of the embryo transfer, were undergoing

their first IVF cycle, had an endometrial thickness of

≥8 mm, and had at least two good-quality embryos

available for transfer or freezing. Good-quality

embryos were defined by their morphological

features and cleavage rate, and included embryos

with less than 25% fragmentation and four cells at

day 2. Eligible patients were individually counselled

about eSET. Women who opted for eSET would have

one embryo replaced (eSET group), while those who

opted for DET had two embryos transferred (DET

group).

Ovarian stimulation and in-vitro fertilisation/intra-cytoplasmic sperm injection procedures

All women were treated either with the long

gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) agonist

protocol or the GnRH antagonist protocol for

pituitary down-regulation. The details of the long

protocol for the ovarian stimulation regimen,

handling of gametes, as well as standard insemination

and ICSI were as previously described.9 In short,

women received buserelin (Suprecur; Hoechst,

Frankfurt, Germany) nasal spray 150 μg 4 times a

day starting from the mid-luteal phase of the cycle

preceding the treatment cycle, followed by human

menopausal gonadotropins (hMG) or recombinant

follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH) for ovarian

stimulation after return of a period. In the GnRH

antagonist protocol, after confirming a basal serum

oestradiol level, ovarian stimulation was started

with either hMG or recombinant FSH. Ganirelix

(NV Organon; Swords Co, Dublin, Ireland) 250 μg

was started from the sixth day of stimulation. The

starting dose of gonadotropin was based on the

baseline antral follicle count.

Transvaginal ultrasonography was used to

monitor the ovarian response. When the mean

diameter of the leading follicle reached 18 mm and

there were at least three follicles reaching a mean

diameter of 16 mm or more, human chorionic

gonadotropin (hCG; Pregnyl; Organon, Oss,

The Netherlands) 5000 or 10 000 units or Ovidrel

(Merck Serono, Modugno, Italy) 250 μg was given

and oocytes were collected about 36 hours later.

Fertilisation was carried out in vitro either by conventional insemination or ICSI depending on

semen parameters. Women were allowed to have

replacement of at most two embryos 2 days after

oocyte retrieval. A progesterone pessary (Endometrin

100 mg twice per day; Ferring Pharmaceuticals,

Parsippany [NJ], US) was administered from the

day of embryo transfer for 2 weeks to enable luteal

support. Pregnancies were confirmed by positive

urine hCG tests and transvaginal ultrasonographic

evidence of a gestational sac.

Collection of clinical information

Clinical information including age, body mass index,

basal serum levels of FSH, and baseline antral follicle

counts were collected. During IVF treatment, such

data included days of stimulation, total dosage of

gonadotropin, oestradiol level on day of hCG,

number of oocytes retrieved, number of available

embryos, number of good-quality embryos, as well

as pregnancy and miscarriage rates.

Clinically, pregnancy was defined as the

presence of a gestational sac by ultrasonography,

whereas the miscarriage rate per clinical pregnancy

was defined as the proportion of patients whose

pregnancy failed to develop before 20 weeks of

gestation. Pregnancy outcome was collected from

all pregnant women by a postal questionnaire or by

phone. Live birth was defined as the delivery of a

fetus with signs of life after 24 completed weeks of

gestational age, and the multiple pregnancy rate was

calculated as the number of multiple pregnancies

divided by the number of clinical pregnancies,

expressed as a percentage. Obstetric outcomes

including antenatal complications, gestational age

at delivery, mode of delivery, and birth weight were

also recorded.

Statistical analysis

The primary outcome measure was the live birth

rate and secondary outcomes included the multiple

pregnancy rate and obstetric outcomes. Statistical

analysis for the comparison of mean values was

performed using Mann-Whitney and Student’s t

tests, as appropriate. The Chi squared and Fisher’s

exact tests were used to compare categorical

variables. Statistical analysis was carried out using

the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences

(Windows version 20.0; SPSS Inc, Chicago [IL],

US). A two-tailed P value of <0.05 was considered

statistically significant.

Results

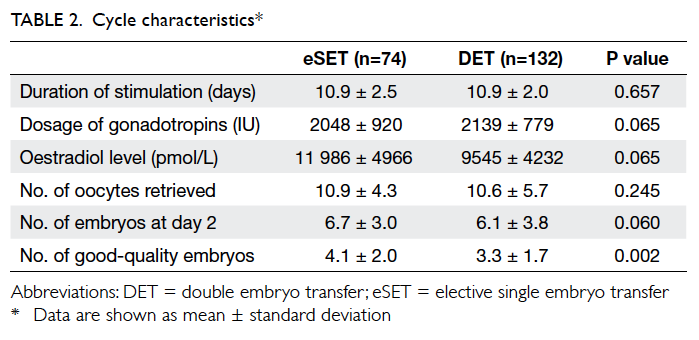

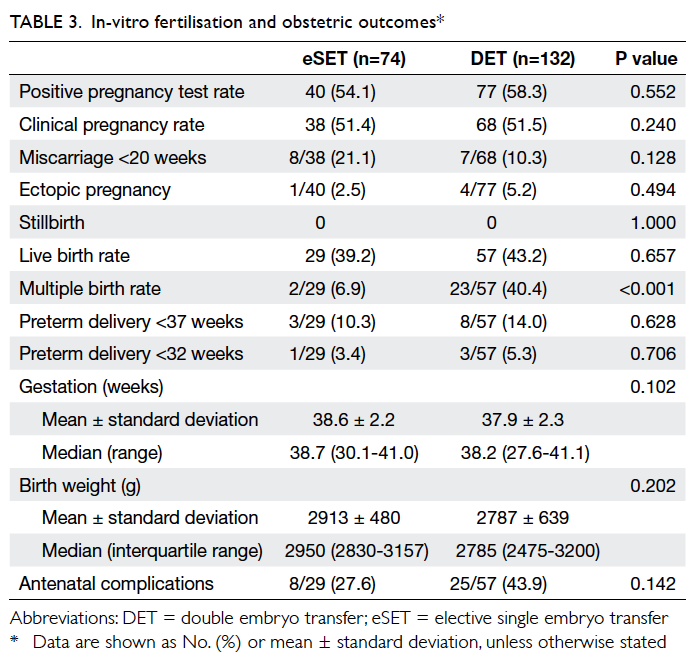

In all, 206 women undergoing their first IVF cycle

from October 2009 to December 2011 met the

inclusion criteria. A total of 74 women chose eSET

and 132 chose DET. Patient and cycle characteristics

are shown in Tables 1 and 2, respectively. Women who opted for eSET were significantly younger than

those opting for DET, and had a significantly higher

proportion of good-quality embryos than those in

the DET group.

Table 1. Demographic and clinical characteristics of the patients referred for sperm cryopreservation (n=130)*

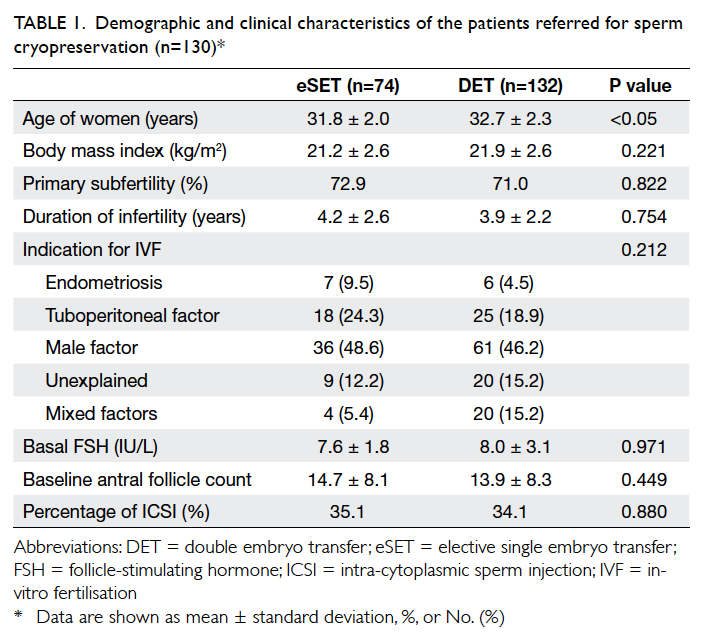

The IVF and obstetric outcomes are shown in

Table 3. Among women with eSET, 40 (54.1%) had

a positive pregnancy test; two were biochemical

pregnancies, eight miscarried, and one was an ectopic

pregnancy. There was one pair of monozygotic and

one pair of dizygotic twins in the eSET group. In

women having DET, the positive pregnancy test rate

was 58.3% (n=77/132); there were nine biochemical

pregnancies, seven miscarriages, and four ectopic

pregnancies. In the DET group, the multiple

pregnancy rate was 40.4%, which was significantly higher than that

in the eSET group (P<0.001). There were two sets

of triplets, of which one underwent fetal reduction

to a singleton and the other had fetal reduction to

twins. One woman in the eSET group and four in the DET group were lost to follow-up for their

obstetric outcomes. Overall, the live birth rate was

comparable in the eSET and DET groups (39.2% vs

43.2%, respectively).

The mean gestational age at birth and

the median birth weight were not significantly

different in the eSET group compared with the

DET group (38.6 ± 2.2 vs 37.9 ± 2.3 weeks and

2950 [interquartile range, 2830-3157] g vs 2785

[2475-3200] g, respectively). The preterm delivery

rate (defined as delivery at <37 weeks) and the

frequencies of antenatal complications (including

gestational diabetes, gestational hypertension, pre-eclampsia,

and placenta praevia) were higher in the

DET group, although the difference did not reach

statistical significance.

Discussion

The risk of multiple pregnancy has been a concern

in IVF/ICSI as it is associated with adverse maternal

and neonatal outcomes.1 This is the first study

reporting live birth rates and obstetric outcomes

after eSET and DET in a selected population in

Hong Kong. Our study confirms recent literature

findings,7 8 by showing that eSET can significantly

reduce the multiple pregnancy rate without adversely

affecting the live birth rate in young women with

good ovarian function. No triplets were observed

in the eSET group, but rather unexpectedly it did

contain two pairs of twins; one was monozygotic and one dizygotic. Dizygotic twin pregnancy following

a single embryo transfer was a rare event, and

suggestive of a spontaneous pregnancy occurring

concurrently with one due to IVF.10 The multiple

pregnancy rate of 40.4% in the DET group and the

live birth rates in our study (39.2% and 43.2% in the

eSET and DET groups, respectively) were similar to

or higher than those previously reported.7 11 12 13 14

Our study showed that the obstetric outcomes

were not significantly different in the two groups.

Antenatal complications were more common in the

DET group (43.9% vs 27.6% in eSET group), although

the difference did not reach statistical significance

(P=0.142). Regrettably, data on the Apgar score,

neonatal intensive care unit admissions, and

perinatal mortality were not available. A recent meta-analysis

by Grady et al15 showed that eSET babies

were associated with decreased risks of preterm

birth and low birth weight than those involving DET.

Moreover, eSET singletons had a higher birth weight

and lower preterm birth rate than DET singletons,

which was postulated to be related to the vanishing

twin.16 Our study failed to demonstrate the difference

but this could be attributed to the small sample size.

Our study was limited by its retrospective

nature and small sample size. Also, women having

eSET were significantly younger than those having

DET, which might lead to possible confounding.

The younger mean age in the eSET group could

explain the higher number of good-quality embryos

available for transfer, which might have an impact

on the cumulative pregnancy rate. The cumulative

pregnancy rate was not always included as many

women still had frozen embryos, but this would be an

important aspect to look into in the future. Another

bias was that women were allowed to choose between

one or two embryos to transfer, instead of allocation

by randomisation. Nonetheless, it reflected the

actual situation in our centre. Blastocyst transfer is

not routinely performed in out unit, because of the

possible increased risk of congenital abnormalities

and preterm labour,17 18 although the pregnancy and

live birth rates of the fresh cycle may be higher than

those following early cleavage stage transfer.19

The eSET policy is increasingly being applied

and in a country like Belgium, the law requires eSET

for all patients aged under 36 years during their

first two IVF attempts.20 In Hong Kong, eSET is not

imposed and suitable women were given the choice

of eSET and DET with detailed counselling. From our

data, only a third of the women chose eSET, which

suggests that such women are still resistant to eSET.

Child et al21 found that 41% of women having assisted

reproductive technology were actually inclined to

prefer a twin pregnancy, and some women waiting

for IVF treatment viewed severe child disability

outcomes more desirable than having no child at

all.22 This barrier might be overcome by providing educational material to women so as to improve

their knowledge on outcomes and risks of multiple

pregnancies.23 The feasibility of eSET also relies on

improving outcomes with cryopreserved embryos

and the technique on vitrification. Information from

the present study may also improve the uptake of

eSET in the unit.

Our study confirms that when compared

with DET, eSET can reduce the rate of multiple

pregnancies without compromising the live birth

rate in the fresh cycle. Elective SET should be offered

to patients with a good prognosis and IVF centres

should promote it, whenever appropriate, through

provider and patient education.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Mr TM Cheung for

data collection.

Declaration

No conflicts of interest were declared by the authors.

References

1. Pinborg A. IVF/ICSI twin pregnancies: risks and prevention. Hum Reprod Update 2005;11:575-93. CrossRef

2. Land JA, Evers JL. Risks and complications in assisted reproduction techniques: report of an ESHRE consensus meeting. Hum Reprod 2003;18:455-7. CrossRef

3. Council on Human Reproductive Technology, Hong Kong. Code of Practice on Reproductive Technology & Embryo Research. Available from: http://www.chrt.org.hk/english/service/service_cod.html. Accessed Apr 2013.

4. HFEA reduces maximum number of embryos transferred in single IVF treatment from three to two [press release]. Human Fertilisation and Embryology Authority; 2001 Aug 8.

5. Prevention of twin pregnancies after IVF/ICSI by single embryo transfer. ESHRE Campus Course Report. Hum Reprod 2001;16:790-800.

6. Cutting R, Morroll D, Roberts SA, Pickering S, Rutherford A; BFS and ACE. Elective single embryo transfer: guidelines for practice British Fertility Society and Association of Clinical Embryologists. Hum Fertil (Camb) 2008;11:131-46. CrossRef

7. McLernon DJ, Harrild K, Bergh C, et al. Clinical effectiveness of elective single versus double embryo transfer: meta-analysis of individual patient data from randomised trials. BMJ 2010;341:c6945. CrossRef

8. Pandian Z, Bhattacharya S, Ozturk O. Number of embryos for transfer following in vitro fertilization or intracytoplasmic sperm injection. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2009:CD003416.

9. Ng EH, Yeung WS, Lau EY, So WW, Ho PC. High serum oestradiol levels in fresh IVF cycles do not impair implantation and pregnancy rates in subsequent FET cycles. Hum Reprod 2000;15:250-5. CrossRef

10. Van der Hoorn ML, Helmerhorst F, Claas F, Scherjon S. Dizygotic twin pregnancy after transfer of one embryo. Fertil Steril 2011;95:805.e1-3.

11. Gremeau AS, Brugnon F, Bouraoui Z, Pekrishvili R, Janny L, Pouly JL. Outcome and feasibility of elective single embryo transfer (eSET) policy for the first and second IVF/ICSI attempts. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol 2012;160:45-50. CrossRef

12. Fauque P, Jouannet P, Davy C, et al. Cumulative results including obstetrical and neonatal outcome of fresh and frozen-thawed cycles in elective single versus double fresh embryo transfers. Fertil Steril 2010;94:927-35. CrossRef

13. Thurin A, Hausken J, Hillensjo T, et al. Elective single-embryo transfer versus double-embryo transfer in in vitro fertilization. N Engl J Med 2004;351:2392-402. CrossRef

14. Council on Human Reproductive Technology, Hong Kong. Reports and statistics. CHRT website: www.chrt.org.hk/english/publications/publications_rep.html. Accessed Apr 2013.

15. Grady R, Alavi N, Vale R, et al. Elective single embryo transfer and perinatal outcomes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Fertil Steril 2012;97:324-31. CrossRef

16. De Sutter P, Delbaere I, Gerris J, et al. Birthweight of singletons after assisted reproduction is higher after single- than after double-embryo transfer. Hum Reprod 2006;21:2633-7. CrossRef

17. Källén B, Finnström O, Lindam A, Nilsson E, Nygren KG, Olausson PO. Blastocyst versus cleavage stage transfer in in vitro fertilization: differences in neonatal outcome? Fertil Steril 2010;94:1680-3. CrossRef

18. Dar S, Librach CL, Gunby J, et al. Increased risk of preterm birth in singleton pregnancies after blastocyst versus Day 3 embryo transfer: Canadian ART Register (CARTR) analysis. Hum Reprod 2013;28:924-8. CrossRef

19. Glujovsky D, Blake D, Farquhar C, Bardach A. Cleavage stage versus blastocyst stag embryo transfer in assisted reproductive technology. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2012;7:CD002118.

20. Debrock S, Spiessens C, Meuleman C, et al. New Belgian legislation regarding the limitation of transferable embryos in in vitro fertilization cycles does not significantly influence the pregnancy rate but reduces the multiple pregnancy rate in a threefold way in the Leuven University Fertility Center. Fertil Steril 2005;83:1572-4. CrossRef

21. Child TJ, Henderson AM, Tan SL. The desire for multiple pregnancy in male and female infertility patients. Hum Reprod 2004;19:558-61. CrossRef

22. Scotland GS, McNamee P, Peddie VL, Bhattacharya S. Safety versus success in elective single embryo transfer: women’s preferences for outcomes of in vitro fertilization. BJOG 2007;114:977-83. CrossRef

23. Hope N, Rombauts L. Can an educational DVD improve the acceptability of elective single embryo transfer? A randomized controlled study. Fertil Steril 2010;94:489-95. CrossRef