Hong Kong Med J 2025;31:Epub 2 Dec 2025

© Hong Kong Academy of Medicine. CC BY-NC-ND 4.0

CASE REPORT

Successful treatment of adult atypical haemolytic uraemic syndrome with multi-organ involvement: a case report

YK Yam, MB, ChB, MRCP1; Alison LT Ma, FRCPCH, FHKAM (Paediatrics)2; Zoe SY Tsang, MB, ChB, MRCP1; SK Yuen, FRCP, FHKAM (Medicine)1

1 Department of Medicine and Geriatrics, Caritas Medical Centre, Hong Kong SAR, China

2 Department of Paediatrics and Adolescent Medicine, Hong Kong Children’s Hospital, Hong Kong SAR, China

Corresponding author: Dr SK Yuen (yuensk@ha.org.hk)

Case presentation

A 51-year-old Chinese woman presented with status

epilepticus in May 2024. Four months previously, she

had been admitted for abdominal pain. Computed

tomography (CT) of the abdomen and pelvis at the

time was unremarkable. She had remained well until

she developed upper respiratory tract infection

symptoms, followed by recurrent abdominal

pain and vomiting for 2 days. Her mental status

deteriorated with irritability and mutism, followed

by recurrent generalised tonic-clonic seizures.

Physical examination was unremarkable. She was

intubated and managed in the intensive care unit

with multiple anticonvulsants.

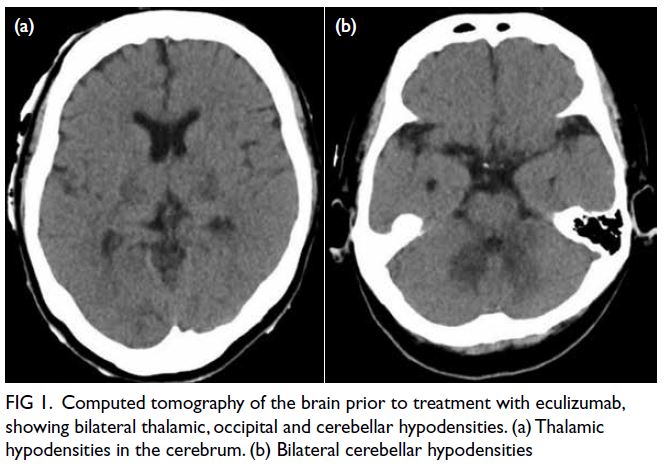

The initial plain CT of the brain was normal,

but follow-up CT revealed new bilateral cerebellar,

thalamic and occipital hypodensities (Fig 1). Blood

tests showed thrombocytopenia (platelet count:

36×109/L, reference: 145-370) and acute kidney

injury (creatinine level: 663 μmol/L, reference: 49-83).

Haemoglobin level dropped to 6.6 g/dL (reference: 11.7-14.9) over the subsequent days with identifiable

schistocytes, raised lactate dehydrogenase level

(2532 U/L, reference: 103-199), raised indirect

bilirubin level (direct-to-total bilirubin: 14:39 μmol/L),

undetectable haptoglobin level (<0.07 g/L, reference:

0.30-2.00), reticulocytosis (133.2×109/L, reference:

20-101; 5.9%) and negative direct antiglobulin

test, suggestive of microangiopathic haemolytic

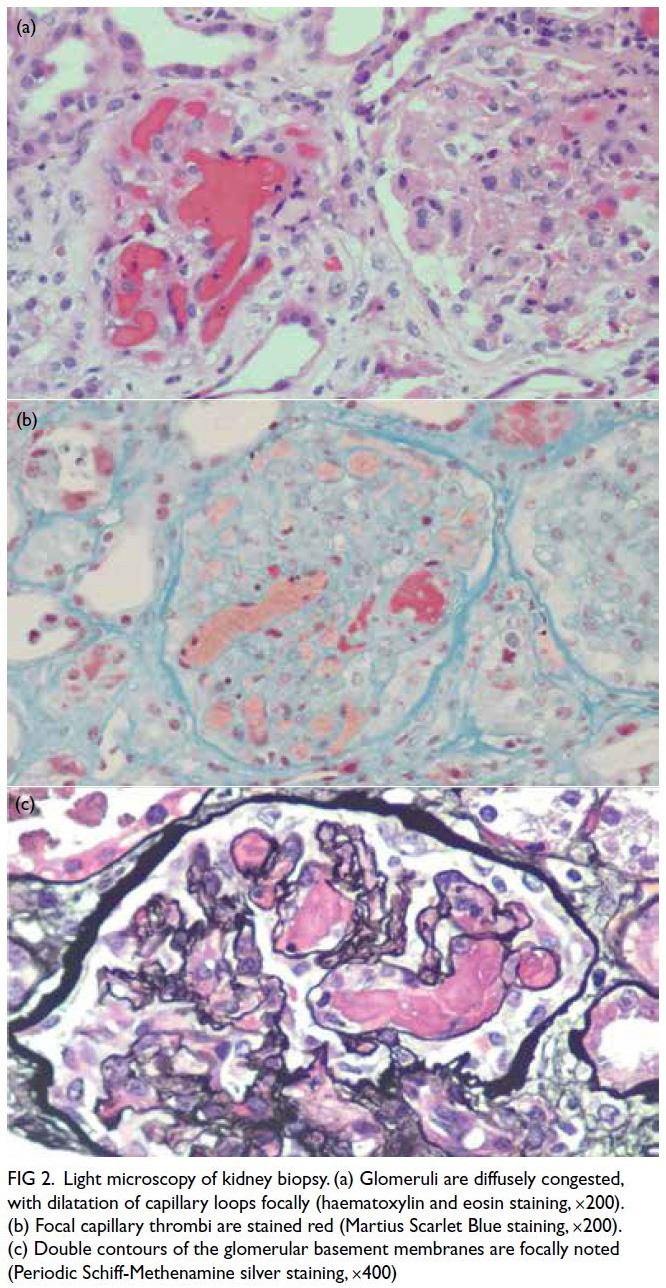

anaemia. Kidney biopsy confirmed thrombotic

microangiopathy (TMA) with congested glomeruli,

double contours, and capillary thrombi on fibrin

staining (Fig 2).

Figure 1. Computed tomography of the brain prior to treatment with eculizumab, showing bilateral thalamic, occipital and cerebellar hypodensities. (a) Thalamic hypodensities in the cerebrum. (b) Bilateral cerebellar hypodensities

Figure 2. Light microscopy of kidney biopsy. (a) Glomeruli are diffusely congested, with dilatation of capillary loops focally (haematoxylin and eosin staining, ×200). (b) Focal capillary thrombi are stained red (Martius Scarlet Blue staining, ×200). (c) Double contours of the glomerular basement membranes are focally noted (Periodic Schiff-Methenamine silver staining, ×400)

ADAMTS13 activity was normal at 75.4%

(reference: 60.6%-130.6%; <10% signifies severe

deficiency1). Stool culture and polymerase chain

reaction for Shiga toxin genes, urine Streptococcus

pneumoniae soluble polysaccharide antigen,

polymerase chain reaction of nasopharyngeal

swab for common respiratory viruses, as well as

serological tests for human immunodeficiency

virus, cytomegalovirus and Epstein-Barr virus

were all negative. Antinuclear antibodies, anti–double-stranded DNA antibodies, antiphospholipid

antibodies, antibodies to extractable nuclear antigen,

anti–topoisomerase I antibody and antineutrophil

cytoplasmic antibodies were likewise negative.

Complement component 3 and complement

component 4 were normal. Results of homocysteine

and amino acid chromatography excluded cobalamin

C deficiency. Urine tests were negative for pregnancy

and drugs that might induce TMA. There were

no clinical features suggestive of malignancy. The

diagnosis of atypical haemolytic uraemic syndrome

(aHUS) with multisystem (gastrointestinal,

neurological and kidney) involvement, possibly

triggered by upper respiratory tract infection,

was made. The patient was apnoeic and anuric,

necessitating ventilatory and haemodialysis support.

Experience sharing from paediatric nephrology

colleagues facilitated prompt testing for anti–factor

H antibody (anti-FH), complement functional assays

(CH50, AH50, and sC5b9) and genetic analysis for

variants related to aHUS. Urgent application was made through the expert panel of the Hospital

Authority for eculizumab, a complement component

5 (C5) inhibitor. Anti–factor H antibody level

was raised to 11.6 U/mL (reference: <10) but no

pathogenic variants were detected by next-generation

sequencing or multiplex ligation-dependent probe

amplification analysis of the aHUS genetic panel including the following genes: CFH, CFB, CFI, MCP, C3, CFHR1, CFHR3, CFHR5, DGKE and MMACHC

(see online Appendix for the full names of genes).

In view of the likely diagnosis of complement-mediated

HUS, the first dose of eculizumab was

given 7 days after admission. Improvement in

haematological indices and renal recovery were

evident within the first and third week, respectively.

She was extubated 12 days after eculizumab

commencement and had been weaned off

haemodialysis after 4 weeks. Repeat CT of the brain

confirmed resolution of previous abnormalities

(Fig 1). She was seizure-free and ambulatory

with full neurological recovery upon discharge

at 10 weeks post-hospitalisation. Prednisolone

and mycophenolate mofetil were started while

eculizumab was weaned off after 28 weeks of

treatment. Her platelet count, lactate dehydrogenase

level, haptoglobin level and kidney function have

remained normal on serial monitoring.

Discussion

Atypical haemolytic uraemic syndrome is a form of

TMA caused by dysregulation of the complement

pathway.1 The nomenclature of the disease is

evolving.2 In 50% to 60% of patients, either

complement gene variants or anti-FH autoantibodies

result in dysregulation of the alternative pathway.1

Clinical features include microangiopathic

haemolytic anaemia, thrombocytopenia and end-organ

injury, most commonly acute kidney injury.3

Extrarenal manifestations involving neurological,

gastrointestinal, pulmonary and cardiovascular

systems are also seen.4 Half of the affected cases are

preceded by triggers such as infections, medications

and pregnancy.1 The annual incidence of aHUS has

been reported as 0.5 to 2 per million, of whom 41%

to 58% of cases are adults.1 This is contrary to the

traditional belief that it is a childhood condition.1

Under recognition of aHUS might be attributed

to inexperience of the disease and its diagnostic

algorithm.

The diagnosis of aHUS requires urgent

evaluation to exclude other types of TMA, namely

thrombotic thrombocytopenia, Shiga toxin–producing Escherichia coli–haemolytic uraemic

syndrome and different secondary forms.3 It is often

a challenge to differentiate a complement-mediated

TMA with a trigger from a secondary TMA. A full

battery of tests is required to thoroughly exclude

alternative diagnoses once TMA is recognised,5 as in

our case. Complement studies, anti-FH antibody titre

and genetic analysis are essential in the diagnostic

pathway.5 A normal complement component 3

level in our patient was not surprising since it is

reported low in only about 50% of cases.3 Genetic

screening is particularly important as it correlates

with the response to treatment, risk of relapse, and prognosis.3 Nevertheless a negative genetic test does

not exclude the diagnosis of complement-mediated

TMA since about 40% of patients have no variants

identified.5

The outcome of aHUS has been historically

poor prior to the development of complement

inhibitors. Eculizumab and ravulizumab are anti-C5

monoclonal antibodies that block the terminal

complement pathway.5 Eculizumab has been shown

to prolong the 5-year end-stage kidney disease-free

survival of aHUS patients from 39.5% to 85.5%.5 In

Hong Kong, eculizumab or ravulizumab may be

publicly funded for indicated patients, but only with

prior approval from a local expert panel.6 Physicians

should take note of the available resources, including

the diagnostic and management pathways, and the

funding procedure in relation to aHUS to facilitate

appropriate patient care.

This case illustrates the effect response of an

adult patient with complement-mediated aHUS to

C5 inhibitors, highlighting the importance of timely

recognition, evaluation and management of this rare

condition.

Author contributions

Concept or design: YK Yam, SK Yuen.

Acquisition of data: YK Yam.

Analysis or interpretation of data: All authors.

Drafting of the manuscript: YK Yam.

Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: All authors.

Acquisition of data: YK Yam.

Analysis or interpretation of data: All authors.

Drafting of the manuscript: YK Yam.

Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: All authors.

All authors had full access to the data, contributed to the study, approved the final version for publication, and take responsibility for its accuracy and integrity.

Conflicts of interest

All authors have disclosed no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgement

The authors acknowledge the invaluable contribution of the

Intensive Care Unit and the Department of Pathology at the

Caritas Medical Centre in the care of this patient.

Declaration

Preliminary results of the case have been presented as poster

presentation at the 5th International Congress of Chinese

Nephrologists cum Hong Kong Society of Nephrology Annual Scientific Meeting 2024, Hong Kong, 13-15 December 2024.

Funding/support

This study received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Ethics approval

The patient was treated in accordance with the Declaration of

Helsinki. Informed consent for all treatment and procedures

was obtained from the patient or her next-of-kin. Verbal

consent for publication was obtained from the patient.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material was provided by the authors and

some information may not have been peer reviewed. Any

opinions or recommendations discussed are solely those of the

author(s) and are not endorsed by the Hong Kong Academy

of Medicine and the Hong Kong Medical Association.

The Hong Kong Academy of Medicine and the Hong Kong

Medical Association disclaim all liability and responsibility

arising from any reliance placed on the content.

References

1. Donadelli R, Sinha A, Bagga A, Noris M, Remuzzi G. HUS

and TTP: traversing the disease and the age spectrum.

Semin Nephrol 2023;43:151436. Crossref

2. Nester CM, Feldman DL, Burwick R, et al. An expert

discussion on the atypical hemolytic uremic syndrome

nomenclature—identifying a road map to precision: a

report of a National Kidney Foundation Working Group.

Kidney Int 2024;106:326-36. Crossref

3. Goodship TH, Cook HT, Fakhouri F, et al. Atypical

hemolytic uremic syndrome and C3 glomerulopathy:

conclusions from a “Kidney Disease: Improving Global

Outcomes” (KDIGO) Controversies Conference. Kidney

Int 2017;91:539-51. Crossref

4. Schaefer F, Ardissino G, Ariceta G, et al. Clinical and

genetic predictors of atypical hemolytic uremic syndrome

phenotype and outcome. Kidney Int 2018;94:408-18. Crossref

5. Kavanagh D, Ardissino G, Brocklebank V, et al. Outcomes

from the International Society of Nephrology Hemolytic

Uremic Syndromes International Forum. Kidney Int

2024;106:1038-50. Crossref

6. Hong Kong SAR Government. LCQ16: Support for patients

with rare diseases [press release]. 12 Jun 2024. Available

from: https://www.info.gov.hk/gia/general/202406/12/P2024061200662.htm. Accessed 18 Nov 2025.