Hong Kong Med J 2025;31:Epub 10 Nov 2025

© Hong Kong Academy of Medicine. CC BY-NC-ND 4.0

LETTER TO THE EDITOR

Vitamin B12 deficiency needs to be adequately

diagnosed and treated

TK Kong, FRCP, FHKAM (Medicine)

Division of Geriatric Medicine, Department of Medicine, The University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong SAR, China

Corresponding author: Dr TK Kong (tkkong@hku.hk)

To the Editor—A 79-year-old Chinese male presented

in January 2023 with a 2-week history of depressed

mood and a 2-year history of forgetfulness. He had

no recollection of his COVID-19 illness in December

2022, after which his memory further worsened.

He had been experiencing intermittent dyspepsia

since May 2012, with a finding of Helicobacter

pylori–negative inactive mild chronic antral gastritis

in September 2015, for which he took antacids,

famotidine, and pantoprazole as required. Review

of his history revealed a diagnosis of vitamin B12

deficiency anaemia 10 years earlier in September

2013 when he presented with depression, tiredness,

dizziness, weight loss, hand numbness, and laboratory

findings of macrocytic anaemia (haemoglobin level:

8.2 g/dL, mean cell volume [MCV]: 130.9 fL) along

with a low serum vitamin B12 level (<37 pmol/L).

He was treated with intramuscular cyanocobalamin

for 1 year followed by oral cyanocobalamin 100 mcg

twice a day for 2.5 years. His symptoms improved

and haemoglobin level, MCV (13.7 g/dL and 93.2fL,

respectively, June 2014; 15.1g/dL and 93.7 fL,

respectively, December 2016) and serum vitamin

B12 level (513 pmol/L, September 2014) normalised.

Examination in January 2023 revealed mildly impaired

cognition, depressed mood and positive Romberg

test, but no pallor or glossitis. A clinical diagnosis of

relapsed pernicious anaemia with neuropsychiatric

presentation was made and confirmed by a low

serum vitamin B12 level (<109 pmol/L, January 2023)

and a positive intrinsic factor antibody, although his

haemoglobin level and MCV were normal (14.0 g/dL

and 97.3 fL, respectively). His mood improved but

cognition remained unchanged after high-dose

oral vitamin B12 (mecobalamin 500 mcg 3 times a

day), with normalisation of serum vitamin B12 level

(318 pmol/L, April 2023). The patient was treated

in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Informed consent was obtained for publication of

this case.

This case illustrates the importance of

determining the aetiology of vitamin B12 deficiency,

failure to do so may lead to under-treatment and

disease relapse or progression. Pernicious anaemia

requires lifelong treatment with either parenteral or

high-dose (≥1 g daily) oral vitamin B12. Clinicians and

pathologists should be familiar with both classic and

non-classic presentations, causes, and laboratory

diagnosis of vitamin B12 deficiency, a common

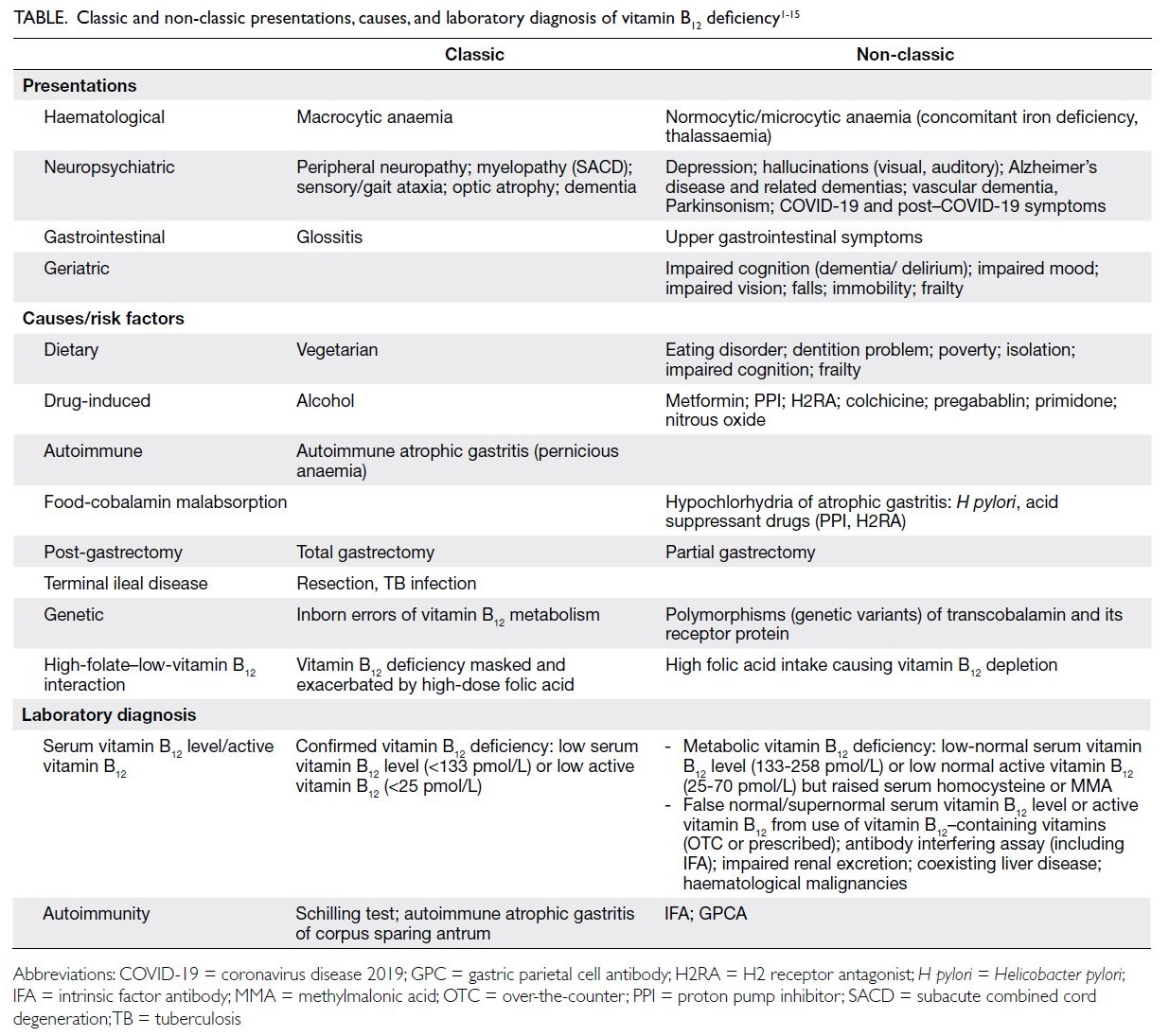

treatable disorder (Table).1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 Neuropsychiatric

presentations can occur in the absence of anaemia or macrocytosis and may be non-classic (eg, depression, long COVID-19, hallucinations).1 2 3 4 5 6

Underlying causes, often multiple in an individual,

need to be diagnosed, and persistent cause(s) require

lifelong treatment.1 Although acid-suppressive

drugs may have contributed to this patient’s vitamin

B12 deficiency (food-cobalamin malabsorption),7

intrinsic factor antibody positivity and dyspepsia

history point to an additional cause in autoimmune

atrophic gastritis. The classic histopathology of this

condition should be confirmed by gastric biopsy,

including both corpus and antrum.8 Periodic

screening for metformin-induced vitamin B12

deficiency in diabetes, though proposed over 50

years ago,9 has only recently been incorporated into

guidelines,1 10 but is not widely practised.

Table. Classic and non-classic presentations, causes, and laboratory diagnosis of vitamin B12 deficiency1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15

Vitamin B12 deficiency can occur in individuals

with apparently normal or supernormal serum

vitamin B12 or active vitamin B12 levels, and clinicians

should be aware of factors that affect test results

(Table).1 2 4 11 12 The 2024 National Institute for

Health and Care Excellence guideline1 introduced an

indeterminate range for low-normal serum vitamin

B12 or active vitamin B12 levels that necessitates further

tests for raised serum homocysteine or methylmalonic

acid (Table) to confirm the diagnosis in those with

risk factors and compatible manifestations of vitamin

B12 deficiency. Because of the limitations of vitamin

B12 levels, the diagnosis and monitoring of treatment

adequacy should not depend solely on its level, but

should instead be guided by clinical judgement and

response.1 Although a low vitamin B12 level in patients

on replacement therapy suggests poor adherence or

inadequate dosing, a normal or high level does not

necessarily indicate adequate treatment and should

not prompt reduction discontinuation.1 The clinical

response should be assessed at follow-up instead

of merely repeating vitamin B12 levels.1 Individual

variability in vitamin B12 treatment response and

dose requirement has been observed, possibly due to

genetic variants of transcobalamin and its receptor.

These variants may reduce vitamin B12 availability and

reduce energy metabolism, ultimately contributing

to frailty.1 2 13

Author contributions

The author solely contributed to the concept or design of the

paper, acquisition of the data, analysis or interpretation of the

data, drafting of the manuscript, and critical revision of the

manuscript for important intellectual content. The author had

full access to the data, contributed to the paper, approved the final version for publication, and takes responsibility for its

accuracy and integrity.

Conflicts of interest

The author has disclosed no conflicts of interest.

Funding/support

This letter received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

References

1. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Vitamin

B12 deficiency in over 16s: diagnosis and management.

NICE guideline; 2024. Available from: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng239. Accessed 10 Aug 2025.

2. McCaddon A. Vitamin B12 in neurology and ageing; clinical

and genetic aspects. Biochimie 2013;95:1066-76. Crossref

3. Lindenbaum J, Healton EB, Savage DG, et al.

Neuropsychiatric disorders caused by cobalamin deficiency

in the absence of anemia or macrocytosis. N Engl J Med

1988;318:1720-8. Crossref

4. Rietsema WJ. Unexpected recovery of moderate cognitive

impairment on treatment with oral methylcobalamin. J Am

Geriatr Soc 2014;62:1611-2. Crossref

5. Batista KS, Cintra VM, Lucena PA, et al. The role of vitamin

B12 in viral infections: a comprehensive review of its relationship with the muscle-gut-brain axis and implications

for SARS-CoV-2 infection. Nutr Rev 2022;80:561-78. Crossref

6. Blom JD. Hallucinations and vitamin B12 deficiency: a

systematic review. Psychopathology 2024;57:492-503. Crossref

7. Andrès E, Affenberger S, Vinzio S, et al. Food-cobalamin

malabsorption in elderly patients: clinical manifestations

and treatment. Am J Med 2005;118:1154-9. Crossref

8. Neumann WL, Coss E, Rugge M, Genta RM. Autoimmune

atrophic gastritis—pathogenesis, pathology and

management. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol 2013;10:529-41. Crossref

9. Tomkin GH, Hadden DR, Weaver JA, Montgomery DA.

Vitamin-B12 status of patients on long-term metformin

therapy. Br Med J 1971;2:685-7. Crossref

10. Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency.

Metformin and reduced vitamin B12 levels: new advice for

monitoring patients at risk. Drug Safety Update. 11 Jun

2022. Available from: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/1084085/June-2022-DSU-PDF.pdf . Accessed 10 Aug 2025.

11. Yang DT, Cook RJ. Spurious elevations of vitamin B12 with

pernicious anemia. N Engl J Med 2012;366:1742-3. Crossref

12. Delgado JA, Pastor García MI, Jiménez NM, et al.

Challenges in the diagnosis of hypervitaminemia B12.

Interference by immunocomplexes. Clin Chim Acta

2023;541:117267. Crossref

13. Matteini AM, Walston JD, Bandeen-Roche K, et al.

Transcobalamin-II variants, decreased vitamin B12

availability and increased risk of frailty. J Nutr Health

Aging 2010;14:73-7. Crossref

14. Mahmud K, Ripley D, Swaim WR, Doscherholmen A.

Hematologic complications of partial gastrectomy. Ann

Surg 1973;177:432-5. Crossref

15. Selhub J, Miller JW, Troen AM, Mason JB, Jacques PF.

Perspective: the high-folate–low-vitamin B-12 interaction

is a novel cause of vitamin B-12 depletion with a specific

etiology—a hypothesis. Adv Nutr 2022;13:16-33. Crossref